Carmen-Olguța Brezuleanu, Mădălina-Maria Brezuleanu, Roxana Mihalache, Irina Susanu, Diana Elena Creangă, Elena Ungureanu

ABSTRACT. Rural development is the second pillar of the Common Agricultural Policy of the European Union (EU), with the role of helping the rural areas of the EU and implicitly Romania to address the economic, environmental, and social challenges they face. The purpose of the research included in this paper is to demonstrate the contribution of the LEADER approach to rural development in Romania, with an emphasis on the North-East Development Region. At the same time, the aim was to highlight the innovative nature of this approach: what it means, how it can be applied, and how it was applied. The data studied through the analysis carried out show that the Romanian territory and, implicitly, the North-East Development Region is poor, fragmented, depopulated, or in the process of depopulating, with few opportunities for young people. The innovative character of the LEADER Programme in Romania and implicitly the North-East Development Region results from the degree of novelty that an investment financed through it brings to the targeted territory, without being limiting and without necessarily presupposing a technological innovation, because the innovation must be evaluated relative to the local situation. The main instrument through which the principles of the LEADER approach can be implemented is the Local Action Group. It is the main driving force behind the activities to be carried out in the territory and which will lead to their implementation. The Local Action Groups set up in the North-East Region provide a common communication framework for local communities to develop and implement Local Development Strategies by initiating, developing and financing projects at local level. They contribute to the unity of local communities and their participation in local development. LEADER approach has brought and how its innovative character is highlighted. The questions that informed its development were: Is this concept considered as a model for sustainable rural development in Romania and the N-E Region? Is LEADER a truly innovative approach. In order to achieve the proposed goal, a multi-step working procedure was developed to allow the collection of target data and additional data derived from the initial target data. Thus, the working procedure was structured in the following steps: problem identification and conceptualization, literature review, document structuring, strategy selection, operational planning, data calculation, and interpretation. Both qualitative and quantitative methods were used in this work. Thus, from a quantitative point of view, the following research methods were considered relevant for obtaining data: administrative data analysis. As a qualitative method, a bibliometric analysis was carried out, i.e., the literature on sustainable rural development through the use of support measures was analysed by means of the VOSviewer programme, using the Web of Science collections database. Without the implementation of the LEADER Programme in Romania and implicitly in the North-East Development Region, rural areas may be deprived of funding that determines the improvement of conditions in that area, but efforts in the field of implementing sustainable rural development measures must be continued so that the effect of this funding is really visible. Thus, the results of the research carried out in the North-East Development Region of Romania add additional value to the information published in previous studies through proposals for rural reform and concrete examples of innovative projects implemented there.

Keywords: LEADER; local action group; North-East Development Region; Romania; rural development.

Cite

ALSE and ACS Style

Brezuleanu, C.-O.; Brezuleanu, M.-M.; Mihalache, R.; Susanu, I.; Creanga, D.E.; Ungureanu, E. Aspects of the contribution of the LEADER approach to rural development in Romania. Case study: North-East Development Region. Journal of Applied Life Sciences and Environment 2024, 57 (1), 37-68.

https://doi.org/10.46909/alse-571123

AMA Style

Brezuleanu C-O, Brezuleanu M-M, Mihalache R, Susanu I, Creanga DE, Ungureanu E. Aspects of the contribution of the LEADER approach to rural development in Romania. Case study: North-East Development Region. Journal of Applied Life Sciences and Environment. 2024; 57 (1): 37-68.

https://doi.org/10.46909/alse-571123

Chicago/Turabian Style

Brezuleanu, Carmen-Olguța, Mădălina-Maria Brezuleanu, Roxana Mihalache, Irina Susanu, Diana Elena Creangă, and Elena Ungureanu. 2024. “Aspects of the contribution of the LEADER approach to rural development in Romania. Case study: North-East Development Region” Journal of Applied Life Sciences and Environment 57, no. 1: 37-68.

https://doi.org/10.46909/alse-571123

View full article (HTML)

Aspects of the Contribution of the Leader Approach to Rural Development in Romania. Case Study: North-East Development Region

Carmen-Olguța BREZULEANU1, Mădălina-Maria BREZULEANU2*, Roxana MIHALACHE3, Irina SUSANU4, Diana Elena CREANGĂ3 and Elena UNGUREANU5

1Department of Control, Expertise and Services, Faculty of Food and Animal Sciences, “Ion Ionescu de la Brad” Iasi University of Life Sciences, 8, Mihail Sadoveanu Alley, 700489, Iasi, Romania; email: olgutabrez@yahoo.ro

2 “Alexandru Ioan Cuza” University of Iasi, 20Ath Carol I Street, 700505, Iasi, Romania

3Department of Agroeconomy, Faculty of Agriculture, “Ion Ionescu de la Brad” Iasi University of Life Sciences,

3, Mihail Sadoveanu Alley, 700490, Iasi, Romania; email: roxana.mihalache@uaiasi.ro; creangadianaelena94@gmail.com

4 ”Dunărea de Jos” University, Galaţi, Romania; e-mail: irinasusanu@gmail.com

5Department of Exact Sciences, Faculty of Horticulture, “Ion Ionescu de la Brad” Iasi University of Life Sciences,

3, Mihail Sadoveanu Alley, 700490, Iasi, Romania; email: elnungureanu@yahoo.com

*Correspondence: brezuleanu.madalina@yahoo.com

Received: Dec. 02, 2023. Revised: Jan. 23, 2024. Accepted: Feb. 01, 2024. Published online: Mar. 04, 2024

ABSTRACT. Rural development is the second pillar of the Common Agricultural Policy of the European Union (EU), with the role of helping the rural areas of the EU and implicitly Romania to address the economic, environmental, and social challenges they face. The purpose of the research included in this paper is to demonstrate the contribution of the LEADER approach to rural development in Romania, with an emphasis on the North-East Development Region. At the same time, the aim was to highlight the innovative nature of this approach: what it means, how it can be applied, and how it was applied. The data studied through the analysis carried out show that the Romanian territory and, implicitly, the North-East Development Region is poor, fragmented, depopulated, or in the process of depopulating, with few opportunities for young people. The innovative character of the LEADER Programme in Romania and implicitly the North-East Development Region results from the degree of novelty that an investment financed through it brings to the targeted territory, without being limiting and without necessarily presupposing a technological innovation, because the innovation must be evaluated relative to the local situation. The main instrument through which the principles of the LEADER approach can be implemented is the Local Action Group. It is the main driving force behind the activities to be carried out in the territory and which will lead to their implementation. The Local Action Groups set up in the North-East Region provide a common communication framework for local communities to develop and implement Local Development Strategies by initiating, developing and financing projects at local level. They contribute to the unity of local communities and their participation in local development. LEADER approach has brought and how its innovative character is highlighted. The questions that informed its development were: Is this concept considered as a model for sustainable rural development in Romania and the N-E Region? Is LEADER a truly innovative approach. In order to achieve the proposed goal, a multi-step working procedure was developed to allow the collection of target data and additional data derived from the initial target data. Thus, the working procedure was structured in the following steps: problem identification and conceptualization, literature review, document structuring, strategy selection, operational planning, data calculation, and interpretation. Both qualitative and quantitative methods were used in this work. Thus, from a quantitative point of view, the following research methods were considered relevant for obtaining data: administrative data analysis. As a qualitative method, a bibliometric analysis was carried out, i.e., the literature on sustainable rural development through the use of support measures was analysed by means of the VOSviewer programme, using the Web of Science collections database. Without the implementation of the LEADER Programme in Romania and implicitly in the North-East Development Region, rural areas may be deprived of funding that determines the improvement of conditions in that area, but efforts in the field of implementing sustainable rural development measures must be continued so that the effect of this funding is really visible. Thus, the results of the research carried out in the North-East Development Region of Romania add additional value to the information published in previous studies through proposals for rural reform and concrete examples of innovative projects implemented there.

Keywords: LEADER; local action group; North-East Development Region; Romania; rural development.

INTRODUCTION

Sustainable development seeks to establish a robust theoretical framework for decision-making in any circumstance involving a human-environment link, be it the environment, the economic environment, or the social environment (Czyzewski et al., 2021; Guth et al., 2022). Sustainable rural development refers to actions and initiatives aimed at improving the quality of life in the border areas of urban centres, villages proper, and isolated ones. Rural areas can develop to the extent that there are sources of finance, a prior analysis of needs, and rigorous management afterwards. EU funding available for rural development is provided by the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD) (Klein et al., 2022; Spicka, 2013).

The European Union’s agricultural and rural development policies are an important part of its contribution to achieving the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, which aims to eradicate poverty and hunger, protect the planet from degradation, and prosperity, but only by ensuring progress in harmony with nature. The EU’s rural development and agriculture policies also support other sustainable development goals: goal 1 (poverty-free), goal 8 (decent work and growth), goal 12 (responsible consumption and production), and goal 15 (earth-friendly life) (Czubak and Pawlowski, 2020; Gargano, 2021; Gkatsikos et al., 2022; Veveris and Puzulis, 2019.)

Predominantly rural areas in Europe account for about half of the EU’s land area, with about 20% of the EU population. Most of these places are also among the poorest in the European Union, with Gross domestic product per capita significantly lower than the European average.

The Common Agricultural Policy is a conglomerate of principles aimed at linking food production at continental level with the economic development of rural areas, combined with environmental protection measures to combat climate change, water resource management, and eco-diversity. The Common Agricultural Policy supports the dynamism and economic viability of rural areas through funding and actions supporting rural development (Hoffmann and Hoffmann, 2018; Labianca, 2023; Loizou et al., 2019; Martinho, 2020; Opria et al., 2021).

Therefore, in order to bridge the gap, EU rural development measures under the CAP have been required to contribute to modernising farms, encouraging the adoption and integration of technology and innovation, stimulating rural areas, e.g. through investments in connectivity and basic services, increasing the competitiveness of the agricultural sector, protecting the environment and mitigating climate change, enhancing the vitality of rural communities and ensuring generational renewal in agriculture (Pe’er et al., 2020; Petrea et al., 2021; Ursu and Petre, 2022).

Rural development is the second pillar of the Common Agricultural Policy. It supports the first pillar (income support and market measures) by strengthening the social, economic and environmental sustainability of rural areas.

The CAP contributes to the sustainable development of rural areas by pursuing three long-term goals: increasing agricultural and forestry competitiveness; ensuring sustainable natural resource management and climate action; and achieving balanced territorial development of rural economies and communities, including job creation and maintenance (Creangă et al., 2022). ‘Rural Development’ is co-financed by Member States, whereby they support their farmers through additional measures financed from their national budgets.

The challenges of the new millennium have also brought new challenges for the Common Agricultural Policy. It has had to cope with the demands of a developed society while at the same time protecting and conserving the environment. To this end, a number of reform proposals have been made for the period 2013-2020 such as: sustainability of agriculture, fair distribution of support, reduction of the budget for subsidising large farms while providing additional support for smaller farms, incentives to support young farmers, etc. In the context of heightened environmental and climate concerns, after 2020, the CAP has a new approach with emphasis on: Member States’ autonomy to develop strategic plans based on individual needs and in line with EU objectives, rewards for green practices (green programmes), direct payments will be prioritised to young farmers and smaller farms, but also social protection through commitments to protect workers’ rights (Pe’er et al., 2020).

Rural development refers to actions and initiatives aimed at improving the quality of life in areas bordering urban centres, villages and remote areas. Rural areas can develop as long as there are sources of funding, a prior needs analysis and rigorous management afterwards. EU funding available for rural development is provided from the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD). The EAFRD budget for 2021-2027 amounts to €95.5 billion, which includes a €8.1 billion capital injection from the EU’s next generation recovery instrument to help address the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Thus, the new proposed reforms for the CAP 2023-2027 aim to: better target support for smaller farms, increase the contribution of agriculture to the EU’s environmental and climate objectives, flexibility for Member States to adapt measures to local conditions (EU Council, 2023).

For the period 2023 – 2027, the new Common Agricultural Policy has 9 specific objectives, as follows: supporting young people to stay in rural areas, a sustainable food chain, ensuring and maintaining a steady and reliable income for farmers, rational consumption of natural resources, preserving and protecting biodiversity, developing less-favoured rural areas, combating climate change, improving the competitiveness of the agricultural sector, and protecting health and food quality. Romania, as an EU Member State, implements EAFRD funding through Rural Development Programmes (RDPs) which are co-financed from national budgets and can be drawn up either at national or regional level.

The European Commission approves and monitors the rural development programmes, but decisions on project selection and payments are taken by the national and regional Managing Authorities (Pollermann et al., 2020; Ursu and Petre, 2022).

Thus, the RDP must contribute to the achievement of at least four of the six EAFRD priorities: encourage or accelerate knowledge transfer and innovation in agriculture, forestry, and rural areas, ensure the viability and competitiveness of all branches of agriculture, support the organisation of the food supply chain, ensure animal welfare and risk management in agriculture, and pay greater attention to the efficient use of resources.

LEADER Programme

The LEADER programme is a concept and an initiative of the Common Agricultural Policy of the European Union, introduced in 1991 as an initiative based on a bottom-up approach aimed at supporting the development of disadvantaged rural regions through projects that respond to local needs. Since 2014, the EU has used the LEADER approach called ‘local development placed under community responsibility’ for several EU funding streams in rural, urban and coastal areas (Aubert et al., 2022; Biczkowski, 2020; Figueras et al., 2022).

The premise from which the LEADER approach starts is that a greater added value is obtained compared to the traditional top-down management of EU funds and is based on 7 principles, considered innovative from the perspective of their transposition into practice. They are designed in such a way as to lead to sustainable rural development by: encouraging initiatives and the exploitation of local skills, the “bottom-up” approach, from the “bottom up”, encouraging the accumulation of knowledge regarding local development and its dissemination in other rural areas with which partnerships can be established (Czubak and Pawlowski, 2020; Gargano, 2021).

LEADER already has a history of over 30 years in Europe and over 10 years in Romania. Since its appearance, it has been considered a concept that puts in the foreground the solution of deficiencies in a territory, starting from the realisation of an initial, personalised diagnostic analysis and subsequently the search for solutions that fit the specifics of the area, with the involvement and collaboration of all actors, local, private, and public (Figueras et al., 2022; Hoffmann and Hoffmann, 2018; Navarro et al., 2018). LEADER was expected to be a revolutionary mechanism, the implementation of which has a degree of specificity in each territory depending on the particularities of the area, starting with the observance of some general rules and capitalising on the expertise and experience of local communities in defining their development needs.

The local action group

The purpose of the research carried out in this paper is to demonstrate the contribution of the LEADER approach to rural development in Romania, with an emphasis on the North-East Development Region, and the aim was to highlight the innovative character of this approach: what it means, how it can be applied, and how it was applied. The Local Action Group is the primary mechanism for implementing the LEADER approach’s principles. This is the main engine of the activities that will take place in the territory and that will lead to their application.

At the European level and in Romania, LEADER and its instruments of action in the territory have always evolved, and the Local Action Groups have been in full expansion. If in 2013 there were 2451 LAGs on the territory of Europe, in 2019 their number reached 2784, and in Romania the increase was from 163 in 2012 to 239 in the period 2014–2020. The Local Action Group is a public-private collaboration that is one of the key components of the LEADER strategy. Its job is to design and implement a Local Development Strategy as well as manage financial resources. It is founded on an agreement that requires private partners to own at least 51% of the partnership structure (RNDR, 2023).

The Local Action Groups established in the North-East Development Region provide a common communication framework for local communities in order to elaborate and implement local development strategies by initiating, developing, and financing projects at the local level. They contribute to the unity of local communities and their participation in local development.

Analysing the specialised literature, it was observed that the researchers studied LEADER as an innovative mechanism, the implementation of which has a degree of specificity in each territory according to the particularities of the area, starting from the observance of some general rules and based on expertise and experience local communities have in defining their development needs. However, there is still insufficient evidence on how his novel approach generated positive effects in Romania, so this article addresses this scientific gap. For this, the article aims to examine whether this approach has brought benefits, what these benefits are, and how its innovative character is highlighted (Loizou et al., 2019; Magrini, 2022).

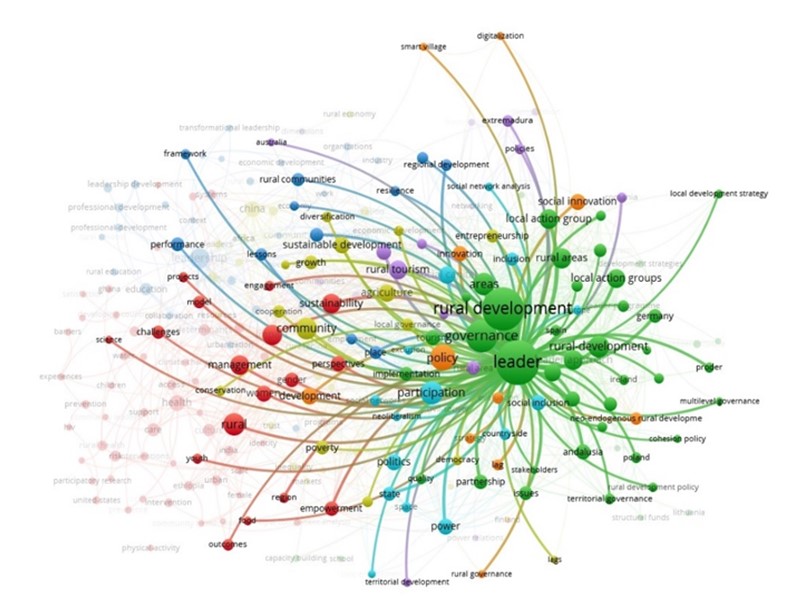

In order to theoretically substantiate the study, we performed a bibliometric analysis of the specialised literature on the topic addressed. The literature on sustainable rural development through the use of support measures was analysed through the VOS viewer programme using the Web of Science collections database. This method represents a preliminary stage of the individual study’s validation.

Research objectives

The research theme brings into discussion an important segment of rural development in Romania as an important element of economic development that cannot be properly achieved without the rural space benefiting from due attention. The analysed aspects will be able to be used to make a socio-economic x-ray of the rural area following the funding received through LEADER, but also of the possible mistakes made in its implementation, in order to be able to indicate new directions to follow in the future. This paper aims to highlight: the quantitative side of LEADER, transposed in the paper through quantitative data (eligible territory, efferent population, financial allocations); the economic side of LEADER, transposed into the work through the amounts allocated through the SDLs, the degree of absorption, the degree of fulfilment of the assumed objectives, the degree of achievement of the indicators; the innovative character of the LEADER approach.

The general objective of the paper refers to the LEADER programme’s contribution to rural development in Romania and its North-East Development Region, namely if it supported the development of the Romanian rural space and if it brought concrete benefits.

As secondary objectives, two questions were formulated regarding its development:

– Is the LEADER programme considered a sustainable rural development model in Romania, respectively, in the N-E Region?

– Is the LEADER programme a truly innovative approach?

The research tools used represented the mechanisms by which the data of the present study were collected and the perceptions that were intended to be relevant for the proposed theme, indicating the results of the implementation of the LEADER approach on the sustainable rural development of Romania and its North-East Development Region, but to indicate the directions that can be followed in the future regarding the management of this innovative approach. From a quantitative point of view, it was considered relevant for obtaining the data that the main research method was the administrative analysis of the data provided by the representative institutions. In order to theoretically substantiate the study, we used a qualitative research method: the bibliometric analysis of the specialised literature on the topic addressed.

Literature review

Numerous international studies, as well as those carried out in Romania, attest to the importance of implementing the LEADER programme as part of the European Union’s Common Agricultural Policy. Thus, following the implementation of the programme, it was found that it has produced positive effects in some of the areas studied, but there are also situations where it should be better adapted to the specificities of rural areas.

Biczkowski (2020), in his research, conducts a comprehensive quantitative and structural evaluation of LEADER projects presented in the context of local resources, which influence development opportunities. The LEADER approach has significantly contributed to mobilizing local resources in rural areas, for example, by increasing the number of Local Action Groups (LAGs) from 149 to 338. It has been observed that the involvement of LAGs has had a significant impact on the activities of residents by increasing the number of initiatives and attracting EU funds.

Strahl et al. (2016) analysed the implementation of the LEADER programme in two EU countries, namely Austria and Ireland, assessing its effects. It was found that the effectiveness could be limited from the perspective of its implementation, recommending a reorientation towards rural development activities in the EU rural reform proposals. The analysis in the article is framed around the concept of social innovation, which is a central aspect of the LEADER programme’s objectives. The analysis was conducted over the period 2007-2013, and it was found that the programme’s implementation did not achieve the desired potential of having a beneficial impact on rural regions; therefore, a re-evaluation was recommended for the Common Agricultural Policy after 2013.

Lewandowska et al. (2021) analyse the financial support provided by EU Structural Funds to stimulate SMEs in Poland. The main goal of the authors’ study is to assess the effects of financial support from various sources in a competitive framework. Following an empirical analysis of 805 firms, the study investigated how SMEs assess financial support. The research results showed that companies did not efficiently utilize the allocated funds, and micro-enterprises were identified as less effective after receiving financial resources allocated through EU support programmes. This support is often demand-oriented, but it was observed that it does not significantly contribute to improving competitiveness among firms.

Lewandowska et al. (2019) in their study aim to identify the determinants of innovation within enterprises in a less developed region of Poland. The influence of EU economic policy instruments on SMEs was examined. The study was based on data from the period 2011-2014. The request for public funds increased the probability of introducing innovations, but not in the initial stage of the Regional Innovation System, but over time. It is important to note that the presented results refer to the term “innovation” in the sense of improvements made at least at the company level and not necessarily the introduction of a new solution in the region, country, or globally. Moreover, developing regions like Podkarpackie are sensitive to the availability of funds, as companies have limited access to funding for high-risk activities, including innovations. It was found that certain types of funding did not lead to significant improvements.

Cañete et al. (2018) in their article investigate the territorial effects of the LEADER approach in Southern Europe, focusing on the Andalusia region in Spain. Their research revealed that, projects were concentrated in the most dynamic areas. In these areas, the economic leadership of the most dynamic municipalities has consolidated at the expense of poorer areas, characterized by little social capital and a small number of enterprises. Therefore, these programmes have not contributed to alleviating territorial imbalances.

Polgár et al. (2015) in their work address aspects of the LEADER programme, such as its timing, its importance for rural development within the EU and especially in Romania, funding measures, and implementation mechanisms. The authors considered the period 2007-2013 for their analysis of the implementation within the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (FEADR) framework and Romania’s contribution.

The purpose of the LEADER programme is to promote the micro-region as a new administrative unit, whose establishment can stimulate development even in the most backward areas of the country. The National Rural Development Programme (PNDR) for the period 2014-2020 has defined new coordinates for rural development, based on innovation, the integrated approach of projects, network collaboration between different areas, as well as local-level funding and management. Transferability and sustainability are two key concepts in this new stage of LEADER programme development.

Pollermann et al. (2020) and Berriet-Solliec et al. (2016) conduct research focusing on ten case studies in European countries. They investigate institutional differences in implementing LEADER at the local level. So, if one important conclusion of this article is that different limitations, as well as local administrative environments, affect how the LEADER programme is carried out locally, then this should be taken into account when creating programmes for rural development

As regards the gap in the literature, it is noted that few studies have been published in the North-East Development Region on the LEADER approach to EU rural reform proposals. Thus, this paper aims to be innovative in that it argues and provides evidence on the use of LEADER instruments to address local problems and argues for the implementation of LEADER as beneficial for development regions, especially for regions facing different types of deprivation, including demographic challenges.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The research undertaken through this paper aims to analyse to what extent the funding received through the M19 LEADER measure supported the development of the Romanian rural space and its North-East Development Region, if the LEADER approach brought concrete benefits, and what the innovative nature of this approach is.

Within the framework of this paper for the general objective of the paper, which refers to the contribution of the LEADER programme to rural development in Romania and its North-Eastern Region, namely if they supported the development of the Romanian rural space, if it brought concrete benefits, as well as for the two secondary objectives: Is this concept (LEADER) considered a sustainable development model in Romania, respectively, in the North-East Development Region?

Is the LEADER programme a truly innovative approach? The methodology used has been selected adequately to provide answers to the research questions, is consistent with the research topic, has been previously analysed, and is relevant to the overall research objective and derived objectives.

In order to observe whether the LEADER concept can be considered a model of sustainable rural development in Romania, respectively in the N-E Region, the analysis and interpretation of quantitative and qualitative data were used to study the perception in Romania and in the North-East Development Region of the impact of the funding received through M19 LEADER.

The analysis and interpretation of the quantitative data had as a time horizon the programming periods 2007–2013 and 2014–2020, while the qualitative data were collected in order to study the perception in the territory of the North-East Development Region of the impact of the funding received through M19 LEADER (MADR M19, 2022).

In order to achieve the proposed goal, a work procedure was developed in several stages that would allow the collection of targeted data as well as additional data derived from those initially targeted. The procedure considers the formal organisation of data, representing an order of successive operations.

Thus, the work procedure was structured in the following stages: identification of the problem and its conceptualization, analysis of specialised literature, structuring of documents, selection of a strategy, operational planning, calculation, and interpretation of data. Scientific research-based quantitative research methods have been used due to the technological evolution of processing tools. Qualitative and quantitative methods were used in this paper, considering that both research methods, namely quantitative research methods and qualitative research methods, have advantages and disadvantages (Brumă et al., 2021; Creangă et al., 2022; Cristea et al., 2021; Labianca, 2023).

The instruments addressed for the 2 questions were predominantly quantitative in nature, to which qualitative instruments were added in order to collect data and perceptions that are relevant to the proposed theme and that indicate the results of the implementation of the LEADER approach on sustainable rural development from the territory studied, but which, at the same time, can also be the promoters of the directions to be followed in the future in terms of the management of this innovative approach.

From a quantitative point of view, the following research methods were considered relevant for obtaining data: administrative data analysis.

Thus, the paper details in detail each research method used depending on the documents studied, the time horizon in which the data were analysed, and the rural area in which the research was done, from the centralization of which the contribution of the LEADER approach to the development was confirmed or denied sustainable rural development, at the level of Romania and in particular of the N-E Region of Romania, the area where the authors of this paper work.

This research method presents the following advantages: accurate information, low cost of investigation, and the possibility of carrying out studies at the level of Romania or zonally (N-E Region of Romania) with a small budget.

For the administrative analysis, a data collection process was carried out from representative official sources (normative acts, public policies) by centralising the data resulting from the progress reports of the local action groups, the data resulting from the operations financed through LEADER measure 19, relevant documents as a result of the implementation of operations, and statistical documents collected by relevant institutions in the field.

The paper studied a time horizon between 2007 and 2020 and analysed documents from which quantitative and qualitative data were collected. Specialised websites of various national and European institutions involved in monitoring and evaluating Local Action Groups and implicitly the LEADER effect were studied (EUR-Lex, 2022; FSPAC, 2021; MADR, 2022; RNDR, 2023).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

For this, the analysis of the specialised literature on sustainable rural development was carried out through the use of support measures analysed through the VOS viewer programme for the entire topic addressed in the paper.

A number of 2641 works or publications were identified following the setting of the limitations specific to the current study, and the keywords that appeared most frequently were “rural development” 117 times and “LEADER” 98 times.

The average number of citations for the top 100 most-cited articles was 97. Most of them were descriptive studies. At a reference threshold of 3, the binding strength was 118.

Information for eligible documents included year of publication, language, journal, title, author, affiliation, keywords, document type, abstract, and number of citations that were exported in TXT format.

The takeover date was August 30.08.2023. VOS viewer (version 1.6.10) was used to analyse Co-authorship, Co-occurrence, Citation, bibliographic coupling, Co-citation and themes.

Two standard weight attributes are applied, which are defined as “Links attribute” and the “Total link strength attribute”.

Following the processing of the database analysed with the reference works, a co-occurrence map of keywords was generated (Figure 1).

Keywords provided by the authors of the paper and appearing more than 5 times in the core WOS database were entered in the final analysis. Of the 4,535 keywords, 117 met the threshold. The keywords that appeared the most were ‘rural development’, ‘Common Agricultural Policy’, ‘sustainability’ and ‘LEADER’.

To inform the current study, 2,641 publications on sustainable rural development were analysed using the supporting measures indexed in the Web of Science database. The specialised literature published includes the following aspects: the analysis of the situation in which the LEADER approach, together with the seven principles that underlie it, and the funding allocated to rural areas have brought added value to the areas that have benefited from funding.

Using the data collected through the presented methods, taking into account statistical variables taken from official statistical databases (e.g., Tempo Online), the existence of correlations between the relative poverty rate and the number of jobs created through LEADER funding, the average number of jobs created/GAL, and the average financial value allocated to the SDL/GAL at the level of Romania and in the N-E Region of Romania.

Next, analysing the data provided by the studied documents (specialist websites of various national and European institutions involved in monitoring and evaluating Local Action Groups and implicitly the LEADER effect), it was found that in Romania and in the N-E study area, the rural population represents an important human resource in the economy, but unfortunately, the standard of living is still very low. The rural space in Romania continues to present important gaps compared to the urban environment, but also within it, depending on the location near the big cities or the economic performance of the region. Disparities are related to labour productivity, access to health and education, public utilities, etc.

As regards the gap in the literature, it is noted that few studies have been published in the North-East Development Region of Romania on the LEADER approach to EU rural reform proposals. Thus, this paper aims to be innovative in that it argues and provides evidence on the use of LEADER instruments to address local problems and argues for the implementation of LEADER as beneficial for development regions, especially for regions facing different types of deprivation, including demographic challenges.

The analysed documents contain numerical and value data related to the number of LAGs, their financial allocation published by the Management Authority, progress reports of the LAG published by the Management Authority, progress reports of the activity from the archive of the LAG, and evaluation reports of the implementation of SDLs at the level of the LAG.

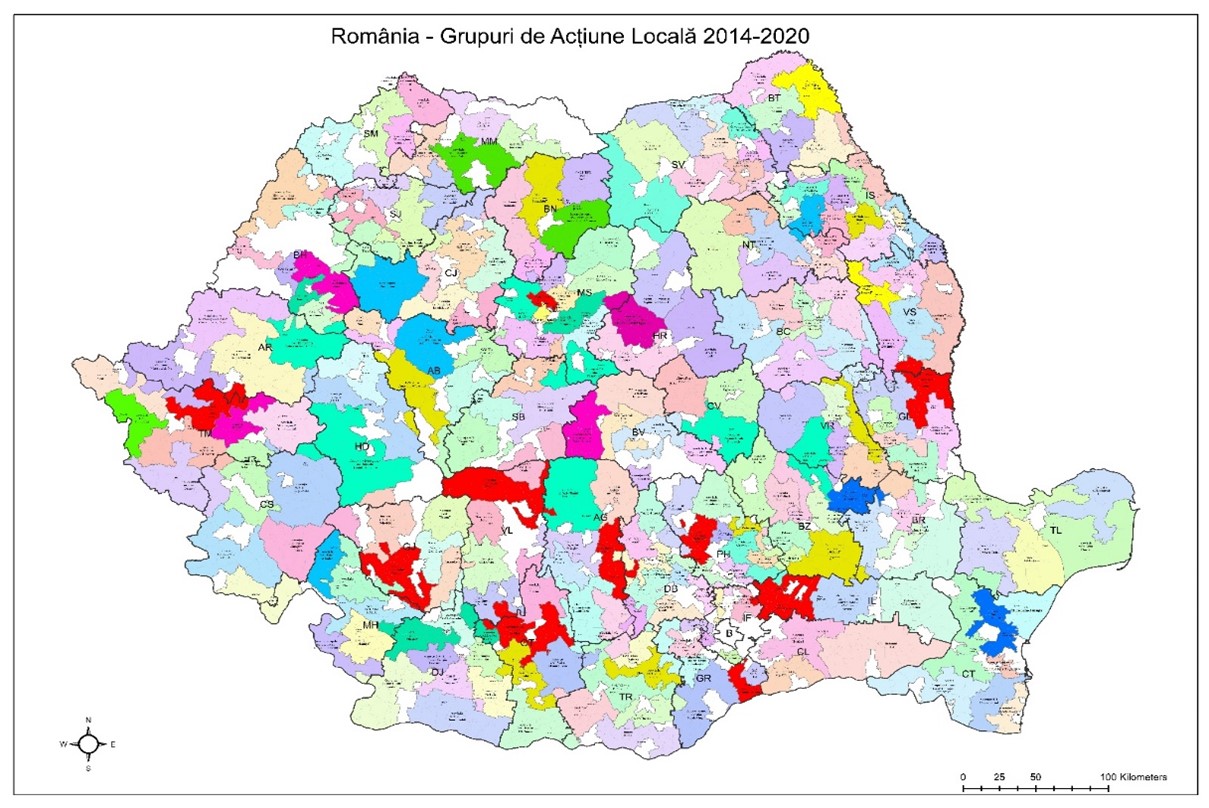

At the European level and in Romania, LEADER and its instruments of action in the territory have always evolved, and the Local Action Groups have been in full expansion. If in 2013 there were 2451 LAGs on the territory of Europe (Figure 2), in 2019 their number reached 2784, and in Romania the increase was from 163 in 2012 to 239 in the period 2014–2020 (EUR-Lex, 2022; MADR, 2022; CE, 2021).

Table 1 provides an overview of LEADER funding foreseen and disbursed for the 2014–2020 programming period. According to this estimates, Member States intend to invest 17% of the administrative and operating expenditures of Local Action Groups. This proportion falls within the limits specified by EU legislation.

According to the European Commission report, local community projects accounted for around 3.05 billion euros at the end of 2020, or 72% of LEADER’s stated expenses (CE, 2021).

It is important to analyse the effects of implementing the principles of this approach in the territory, especially to the extent that it is considered an innovative approach in terms of rural development policies.

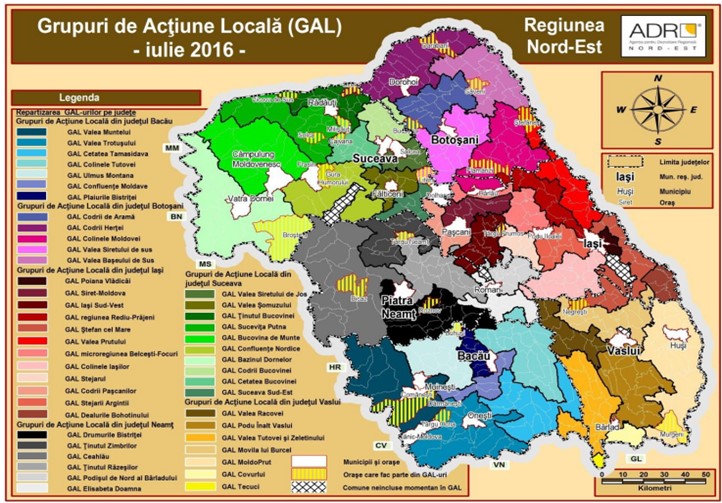

Analysing the Local Action Groups, in Europe in the 2007–2013 and 2014–2020 programming periods, their number has increased, highlighting the success of the LEADER approach because they benefit from expanded powers compared to the previous period, this being an indication of the progress made in implementing the proposed actions in accordance (Figure 3).

In 2017, the number of LAGs in the rural area increased to 47, compared to 32 in 2013, covering 99% of the communes in the North-East Development Region. Only 4 municipalities are not part of LAGs: Săbăoani, Neamț county, Schitu Duca, Iași county, Mălini, Suceava county and Muntenii de Sus, Vaslui county.

Table 1

LEADER financing by cost category by the end of 2020

|

Type of costs |

Planned funding for LEADER (2014 2020) |

Expenditure reported for LEADER (up to the end of 2020) |

||

|

in millions of euros |

% of total funding foreseen for LEADER |

in millions of euros |

% of LEADER funding paid |

|

|

Training costs |

81.6 |

1 % |

67.4 |

2 % |

|

Administrative and running costs |

1 673.6 |

17 % |

1 038 |

24 % |

|

Cooperation activities |

380.9 |

4 % |

98.6 |

2 % |

|

Project costs |

7 794.2 |

78 % |

3 054.4 |

72 % |

|

Total |

9 930.2 |

100 % |

4 258.4 |

100 % |

*Source: European Court of Auditors, based on data provided by the European Commission

Figure 2 – Map of the coverage of the national territory by the selected LAGs in the period 2014–2020 (Source: MADR, 2021)

Of the 29 cities in the region, 22 are part of these LEADER-type LAGs, and 2 of them have over 20,000 inhabitants (Buhuși and Târgu Neamț). The cities that are not part of LAGs are: Slănic Moldova, Frasin, Salcea, Dolhasca, Podu Iloaiei, Hârlău and Comănești (ADR, 2018).

In 2020, the population of the North-East Development Region included in LAG-type associations will reach about 2.4 million people, with the population per LAG varying between about 20,000 people and about 90,000 people.

All LAGs in the North-East Development Region have completed the process of creating Local Development Strategies with support from PNDR under Measure 9.1 and are currently implementing projects financed by different measures of PNDR (M01-M11, M19).

We consider important to mention that the DLRC-type Local Development Strategies (CLLD) of five cities in the North-East Development Region were approved for funding after being judged and chosen in the call for projects 5.1 of POCU 2014–2020. These cities are Bacău, Botoșani, Moinești, Onești, Rădăuți, and Huși. At the same time, following the second call for preparatory support for the development of SDLs, the LAGs from Bârlad and Fălticeni also obtained funding for this purpose.

In order to theoretically substantiate the study, we carried out a qualitative research method: the bibliometric analysis of the specialised literature on the topic addressed (Czytewski et al., 2018).

The literature on sustainable rural development through the use of support measures was analysed through the VOS viewer programme using the Web of Science collections database. This method represents a preliminary stage of the individual study’s validation.

Sustainable development represents, in the Romanian context and implicitly in the N-E Region, the desire and the need to achieve a balance, is intended to start with the citizen, the main actor who seeks an individual balance and favourable conditions to achieve it. The role of the Romanian state in the context of sustainable rural development is to help achieve this balance, not only for current citizens but also for future generations (SD, 2022).

Thus, the need for a regional policy is imposed and oriented, including through the impact of EU funding, in order to be able to reduce the disparities in rural areas.

A lot of great opportunities exist for the LEADER programme in Romania and, by extension, for the N-E Region. These include helping to expand non-agricultural businesses and supporting small businesses in the LEADER area; building, improving, and expanding economic development facilities; and providing small-scale local physical infrastructure, such as broadband and basic services.

According to the studies carried out, it was found that due to unsatisfactory living conditions, the most important problem in the Romanian rural area and implicitly in its N-E region is the migration of the rural population to large urban centres or to other more developed countries.

By implementing the actions provided for in PNDR 2014–2020, this situation wanted to be improved through measures that aimed to increase the level of education and modernise technologies, the efficiency of farms, the use of resources, the basic infrastructure in the rural environment, but also social inclusion and the living standards of the rural population (Dragoi et al., 2017).

Figure 3 – Local Action Groups from the North-East Development Region

Source: Retrieved after ECA (2010)

It was found that the LAGs represented the concrete solution, the transformation into reality of the potential that local communities can capitalise on in order to join this new approach to the development of the Romanian village, an approach that encourages the return and/or settlement of young people in the LEADER territory and its economic, social, and cultural development. To support this approach, the emphasis was placed on stimulating partnerships, knowledge transfer, and the implementation of innovative initiatives, but above all, on the real involvement of citizens in long-term strategic decisions. The Local Action Group operates in a territory eligible for the LEADER programme in Romania, a territory that must meet conditions of size, homogeneity, local identity, density, and number of inhabitants.

The concept of “Local Action Group” came into being with the birth of the LEADER approach in 1991 in Europe, with applicability in Romania starting in 2007–2013. By transposing this concept into Romanian territory, an attempt was made to revitalise the rural space from another perspective and with another approach, namely the LEADER approach. This is a public-private partnership in which the private partners must represent at least 51% (OG 26/2000, 2020) and have met in a Local Development Strategy evaluated and approved by the Management Authority (Staic and Vladu, 2021).

From the analysis of the documents, it was observed that all the needs and specific development needs identified in the area of the LAG proposed directions of action for the sustainable rural development of the perimeter, the financial allocation, and the ways in which these needs can be met, respectively, the financing measures.

The allocation of funding to Local Action Groups was and is being made from the European Fund for Rural Development (FEADR), a fund that finances the second pillar of the CAP: Rural Development, which promotes an endogenous, integrated and territorial approach. Each member state, implicitly Romania, has to allocate for LEADER a minimum of 5% of the amounts received for rural development, or a minimum of 2.5% if it is a newly acceded state (RUE 1305, art. 59, 2013).

The size of the financing was established according to the area of the Local Action Group and the number of inhabitants, being allocated a value of 985.37 euros/km2 and 19.84 euros/inhabitant in the programming period 2014-2020 (OMADR 295, 2016), with the mention that, in the period 2007-2013, the authorised LAGs had fixed allocations distributed but different in the two selection sessions (MADR M19, 2022)

In Romania, the launch of the LEADER programme (2012) created a series of funding opportunities for local rural initiatives that did not find funding in other programmes. The premise from which the LEADER approach starts is that added value is achieved compared to the traditional top-down management of EU funds.

If we analyse the LEADER-eligible area, at the national level, we have 228,754 km2 and 11,359,703 inhabitants, the LEADER-eligible area, and a related eligible population. In the programming period 2007–2013, we will find that the LEADER-eligible surface was covered at a percentage of 63% and the population at a percentage of 58% (ARD, 2022; MADR M19, 2022), according to the cited source.

From the analysis of the documents, it is found that the percentages are slightly different (62% territory, 60% population). In the period 2014-2022, the LEADER-eligible territory reached a degree of coverage of 92%, with the related population representing 86% of the total LEADER-eligible population (2020 SWOT Analysis).

Table 2 presents the situation of the eligible LEADER area occupied by the LAGs in the North-East Development Region in the two programming periods, compared to the national LEADER eligible area, and Table 3 presents the situation of the population related to the national LEADER eligible territory, but also occupied in the two periods of the existence of LEADER in Romania according to the 2011 census.

At the level of Romania, there were 81 Local Action Groups selected in 2009, and another 82 Local Action Groups selected in 2011–2012. The period 2014–2022 resulted in the selection of 76 more LAGs, so at the end of the period, 239 LAGs were authorized (Staic and Vladu, 2021).

The analysis of the documents shows that the period 2014–2020 saw an increase in terms of LAG activity through LEADER. Thus, the number of Local Action Groups experienced an increase of 46.62%, reaching 239, and in the North-East Development Region, 45. The financial allocation in the same period for the uniform development of the rural territory was 985.37 euros/km2 and 19,84 euros/inhabitant, so that the LAGs were able to distribute their received funding more efficiently. The total public value allocated during this period initially totalled 563,516,550.93 euros.

Thus, the average public value allocated per LAG at the national level was 2,357,809.84 euros, according to the data presented in Table 6. The North-East Development Region, the region where most Local Action Groups are found, has a public average/GAL slightly above the national average, respectively 2364734.39 euros, which suggests that although there are many established partnerships, the population density in the area is low compared to other areas.

From the data presented above, it can be seen that the territorial evolution of the LEADER-occupied area and the related population is as follows: in the North-East Development Region, the total eligible LEADER area is 35,089.47 km2. In the period 2014–2020, the eligible occupied LEADER surface increased from 26,150.56 km2 to 33,972.47 km2, respectively, from an occupancy rate of 75% in the period 2007–2013 to 97% in the period 2014–2020.

The total area occupied by LAGs in the first period represented 11% of the total occupied national area and 15% in the second period.

Table 2

Situation of the eligible area occupied in the North-East Development Region compared to Romania in the two programming periods under LEADER, compared to the national LEADER eligible area

|

No crt. |

Region |

National eligible area LEADER km2 |

2007-2013 |

2014-2020 |

||||

|

Surface occupied |

Occupancy rate |

Contribution to national |

Surface occupied |

Occupancy rate |

Contribu-tion to national |

|||

|

km2 |

% |

% |

km2 |

% |

% |

|||

|

1 |

North-East |

35089.47 |

26160.56 |

75 |

11 |

33972.47 |

97 |

15 |

|

2 |

Total |

228754.00 |

142300.47 |

– |

62 |

210442.80 |

– |

92 |

* Source: Own processing according to data MADR (2022)

Table 3

The situation of the population related to the occupied territory in Romania in the two programming periods within the framework of LEADER, compared to the national population eligible for LEADER

|

No crt. |

Region |

Population of national territory LEADER inhabitants |

2007-2013 |

2014-2020 |

||||

|

Population |

Occupancy rate |

Contribution to national |

Population |

Occupancy rate |

Contribu-tion to national |

|||

|

inhabitants |

% |

% |

inhabitants |

% |

% |

|||

|

1 |

North-East |

2241685 |

1530350 |

68 |

13 |

2079156 |

93 |

18 |

|

2 |

Total |

11359703 |

6771629 |

– |

60 |

9760096 |

– |

86 |

*population according to the 2011 Census

Source/Source: Own processing according to MADR (2022) data

It is also noted that the population related to the regional LEADER eligible area in the N-E Region is 2,241,685 inhabitants, or 68% of the total LEADER eligible population in 2007–2013 and 93% in 2014–2020, while in Romania the population related to the territory occupied by the LAGs is 13% in the first period and 18% in the second period.

In the period 2014–2020, the association of farmers in Romania was supported with the help of European funds for rural development, mainly through the strategies of Local Action Groups (LAGs). According to the 2017–2018 CRPE research, more than 75% of the LAG’s strategies offered various funding opportunities for the establishment and development of various farmer association structures. Through the 2014-2020 PNDR, the LAGs started implementing the first cooperative formation support measures in 2017.

Stimulating the formation and development of agricultural cooperatives through the local development strategies of the LAGs in the period 2014-2020 proved to have modest performances. The CRPE research to which almost half of the rural LAGs in Romania responded reveals that, until this moment, 33 cooperatives were established following the launch of the dedicated measure by 50 LAGs. In the case of approx. half of the LAGs that had a measure for cooperatives (Volkov et al, 2019), this assumed individual assistance for the coagulation of cooperatives (community facilitation, trainings), while over 76% included in the category of eligible activities the making of investments. We notice a high heterogeneity in the types of expenses that each LAG thought were necessary to form or develop cooperatives: from establishment to operation, marketing consultancy, management, etc., from promotion to investments. Very few LAGs included all of them.

The LAGs also receive the necessary financial allocation, both for investment measures and for operation, in order to fulfil their assumed objectives. But the funding is not granted without the performance of the Local Action Groups being periodically evaluated, the criteria and the time horizon subject to the evaluation are provided in the specific legislation. The purpose of evaluating the implementation of Local Development Strategies is to highlight the progress achieved and not apply penalties (ECA, 2010). Following these evaluation actions, the Local Action Groups received additional financial allocations for carrying out their activities, or, on the contrary, their funding was withdrawn proportionally.

Also, the LAG has performance indicators provided for in the SDL on the basis of which it operates. These indicators derive from the implementation of projects funded by M19 LEADER and are different for each LAG. Depending on the structure and particularities of each LAG, there are evaluation and monitoring indicators such as: the number of jobs created as a result of the SDL implementation, the number of agricultural holdings supported, the number of non-agricultural businesses supported, and others.

In the period 2014-2020, there were two stages in which the LAGs in Romania and implicitly in the N-E Region were bonused or penalized. (MADR, 2022; RNDDR, 2023). The first bonus session also included penalties and was foreseen since the first version of the Local Development Strategies Implementation Guide, so they could manage their activity in such a way as to receive additional funding and avoid the penalty. The second bonus session, the additional one, intervened along the way, each with specific criteria and different reference periods. The amount of bonuses granted in the basic bonus session, in the amount of 2522162.40 euros, was distributed nationally as follows.

Specifically, the situation of the bonused GALs as well as the premium values for the North-East Development Region, including 2 GALs from Iași County and 3 GALs from Vaslui County, with an allocation of 674,091.52 euros For Iași county: 287,814.43 euros; GAL Iași South West – 189,351.51 euros; GAL Hills of Iasi; 98,462.92 euros. For Vaslui county: 386,277.09 euros: GAL Podu Inalt: 196,925.57 euros; GAL Moldo – Prut: 1 06,036.85 euros; Valea Tutova and Zeletinului Association: 83,314.67 euros. The values related to the penalties in the North-East Development Region were 193,820.53 euros from a LAG from Bacău county, respectively, the Plaiurile Bistriței Local Action Group (Table 4).

Next, from the analysis of the documents, the Local Action Groups that were penalised during the basic bonus session, as well as the criteria not met by each of them, are exemplified nominally. The main condition for the penalty was the non-fulfilment of a minimum contracting degree of 60% of the total value of the SDL, after which the next criterion was analysed. Thus, in Romania, most Local Action Groups received penalties of 85% for the difference between 60%*SDL value and contracted value.

In the N-E Region, the Plaiurile Bistriței LAG received a penalty of 70%, of which 10% was applied for the low efficiency of promoting the measures in the territory in the sense that no projects were submitted that exceeded the amount allocated per funding line (Table 5).

Therefore, in the first stage of the evaluation of the activity of the LAGs, the values collected from the penalties were identical to the bonuses granted. In this way, the value allocated to LEADER, through the Local Development Strategies, has not undergone changes.

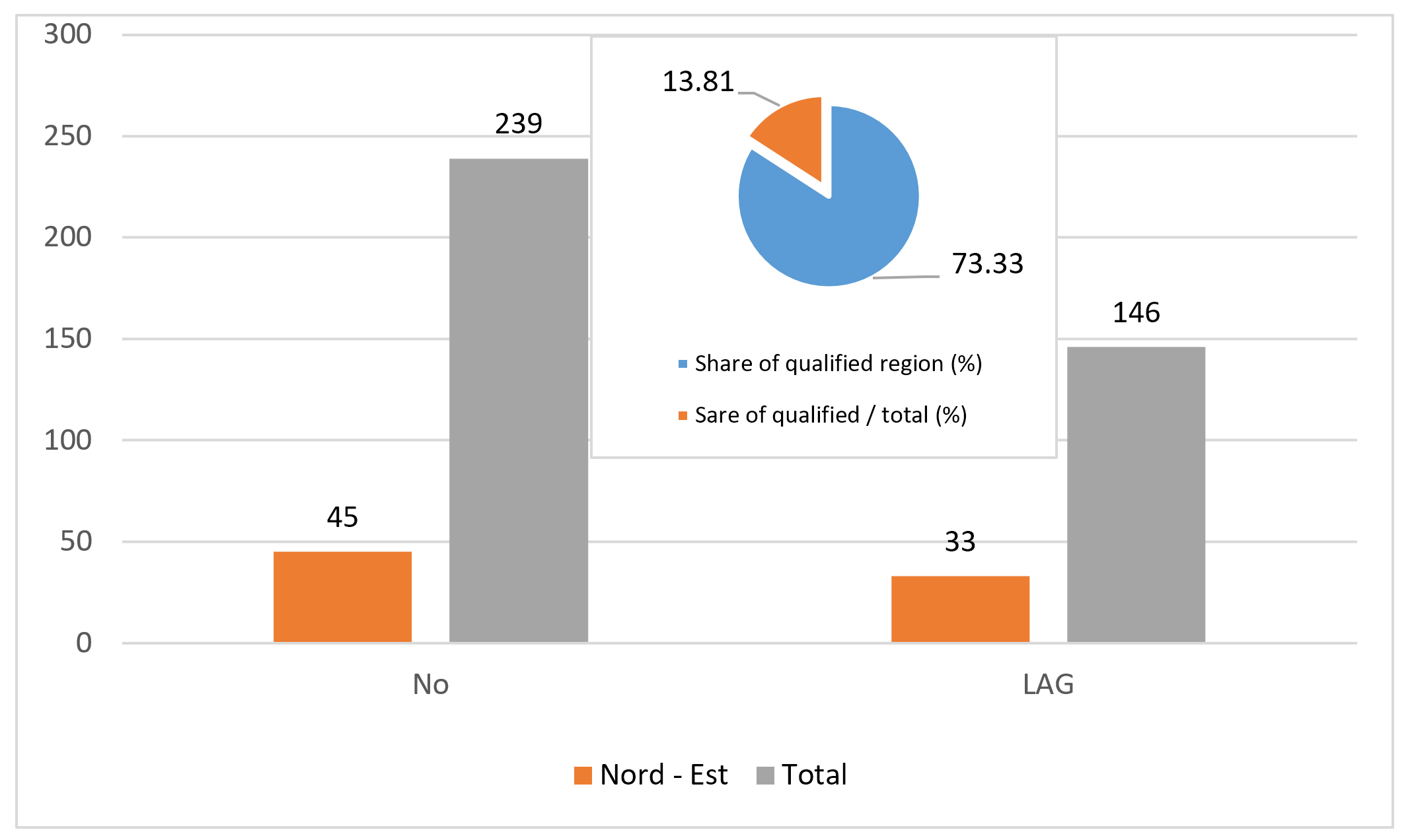

At the level of Romania, 146 LAGs were qualified for the additional bonus, of which 33 LAGs from the North-East Development Region. The granting of the funding was conditional on its use to supplement the budget of the measures for which the SDL received points at the time of authorisation, and as the additional funds came from external sources, the budget allocated to the SDLs in the N-E Region increased from 79,798,405, 37 euros at 86,115,343.38 (R Ev. GAL no. 221327, 2021), with reference to the period 2014 – 2020. (Table 6). Analysing the number of assumed jobs compared to the number of jobs created up to the date of the analysis, at the level of Romania but also of the studied area: the N-E region, it is found that the proposed number has been exceeded.

Table 4

The situation of the bonused GALs and the values allocated according to MADR Order 90/2017 in Romania

|

No. crt. |

Basic bonus according to Order 90/07.04.2017- reference period 2016- 30.09.2019 (OMADR 90, 2017) |

Additional bonus according to Order 41/25.02.2021 – reference period 2016- 30.01.2021 (OMADR 41, 2021) |

|

1 |

Indicators |

Indicators |

|

Achieving a minimum of 60% value |

at least 80% contracted value – |

|

|

contracted value in relation to total SDL |

(sm19.2); |

|

|

error rate of project evaluation – maximum |

at least 50% value paid |

|

|

30%; |

authorised/total SDL value (sm 19.2); |

|

|

Efficiency of animation – no overrated measure. |

jobs created >= 80 % (sm19.2). |

|

|

2 |

Bonus value = 2.522.162,40 euro. |

|

|

3 |

The funds for the bonus come from the amount |

Bonus value = 21.308.364 euro. |

|

4 |

penalties collected. |

The funds come from the amounts available in |

|

5 |

Number of LAGs awarded bonuses = 18. |

sM 19.2 and 19.4 -PNDR 2014-2020. |

|

6 |

The amounts are distributed according to an algorithm. |

Number of LAGs awarded bonuses = 146. |

Table 5

Local Action Groups were penalised, and the main criteria were not met in 2019

|

No. crt. |

Region Development

|

County |

LAG Name |

Unfulfilled penalty criteria |

|||

|

Degree of contracting |

Level Payments – |

Error rate of project evaluation |

Efficiency animation – |

||||

|

– 60%* |

25%* |

5%* |

10%* |

||||

|

1 |

N-E |

Bacău |

Plaiurile Bistriței |

x |

n/a |

n/a |

x |

|

2 |

S-V |

Dolj |

Amaradia Jiu |

x |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Giurgiu |

Asociația pentru Dezvoltare Rurală |

x |

x |

n/a |

n/a |

||

|

3 |

S |

Prahova |

Giurgiu Nord |

|

|

|

|

|

Drumul Voievozilor |

x |

x |

n/a |

n/a |

|||

|

Plaiurile Ramidavei |

x |

n/a |

n/a |

x |

|||

|

Dâmbovița |

Vlașca de Nord |

x |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

||

|

4 |

Centru |

Cluj |

Poarta Apusenilor |

x |

x |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Alba |

GAL Drumul Iancului |

x |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

||

|

5 |

B-Ilfov |

Ilfov |

Sabăr Ilfov Sud |

x |

x |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Ilfov |

Cociovaliștea Ilfov |

x |

x |

n/a |

n/a |

||

|

Ilfov |

Vlăsia Ilfov Nord Est |

x |

x |

n/a |

n/a |

||

|

Ilfov |

Ilfovăț Sud Est |

x |

x |

n/a |

n/a |

||

|

Buzău |

Valea Buzăului |

x |

x |

n/a |

n/a |

||

|

6 |

S-E |

Brăila |

Câmpia Brăilei |

x |

x |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Terasa Brăilei |

x |

x |

n/a |

n/a |

|||

|

7 |

N-V |

Caraș -Severin |

Caraș-Timiș |

x |

x |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Satu- Mare |

Țara Oașului |

x |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

||

|

Bihor |

Valea Velj |

x |

x |

n/a |

x |

||

*the amount of the penalty applied if the criterion is not met; x – unfulfilled criterion; n/a – not the case

Source: Processing according to data MADR (2022)

Table 6

Average for Romania of the three criteria analysed in the case of additional bonusing on 31.01.2021

|

No. crt. |

Region |

Value contracted – euro |

Value SDL- euro (19.2) |

Value paid – euro |

No. Places of work assumed SDL |

No. Places of work created |

No. LAG |

|

1 |

North-East |

79798405.37 |

86115343.38 |

53337129.73 |

479.00 |

549.00 |

45 |

|

2 |

Total |

402901491.91 |

452896852,87 |

255052266.57 |

3245.00 |

3479.00 |

239 |

|

3 |

National average |

1685780.30 |

189.965.91 |

1067164.30 |

13.58 |

14,56 |

– |

Source: Processing according to data MADR (2022)

Thus, from the point of view of the contracted value, the North-East Development Region, from the point of view of the average contracted value, with 1773297.90 euros, paid 66.84% of it and 62.50% of the average SDL value, respectively, 1185269.55 euros, values that indicate a more efficient organisation in the regional perimeter.

The analysis of the indicators revealed the fact that each region, and implicitly the North-East Development Region, has its own specific peculiarities related to location, environmental conditions, climate, resources, the mentality of the inhabitants, and the interests of the zonal leaders, depending on the local desire for the development of each rural space.

Below are the financial allocations received through M19 LEADER. They were intended to improve the standard of living of the inhabitants of the eligible rural perimeter, to improve social capital, to improve local governance, and all of this to determine the evolution towards sustainable rural development.

Since each rural perimeter has its own characteristics depending on the geographical, economic, and social area, at the level of Romania, some areas are more developed than others depending on the territorial resources, the way they are managed, the financial resources, and the ability to distribute them efficiently in territory (so as to determine surplus value) by the existing and limited educational and social infrastructure. A very important characteristic is the degree of involvement of the population, specifically the degree of its responsibility in the creation and development of a sustainable community.

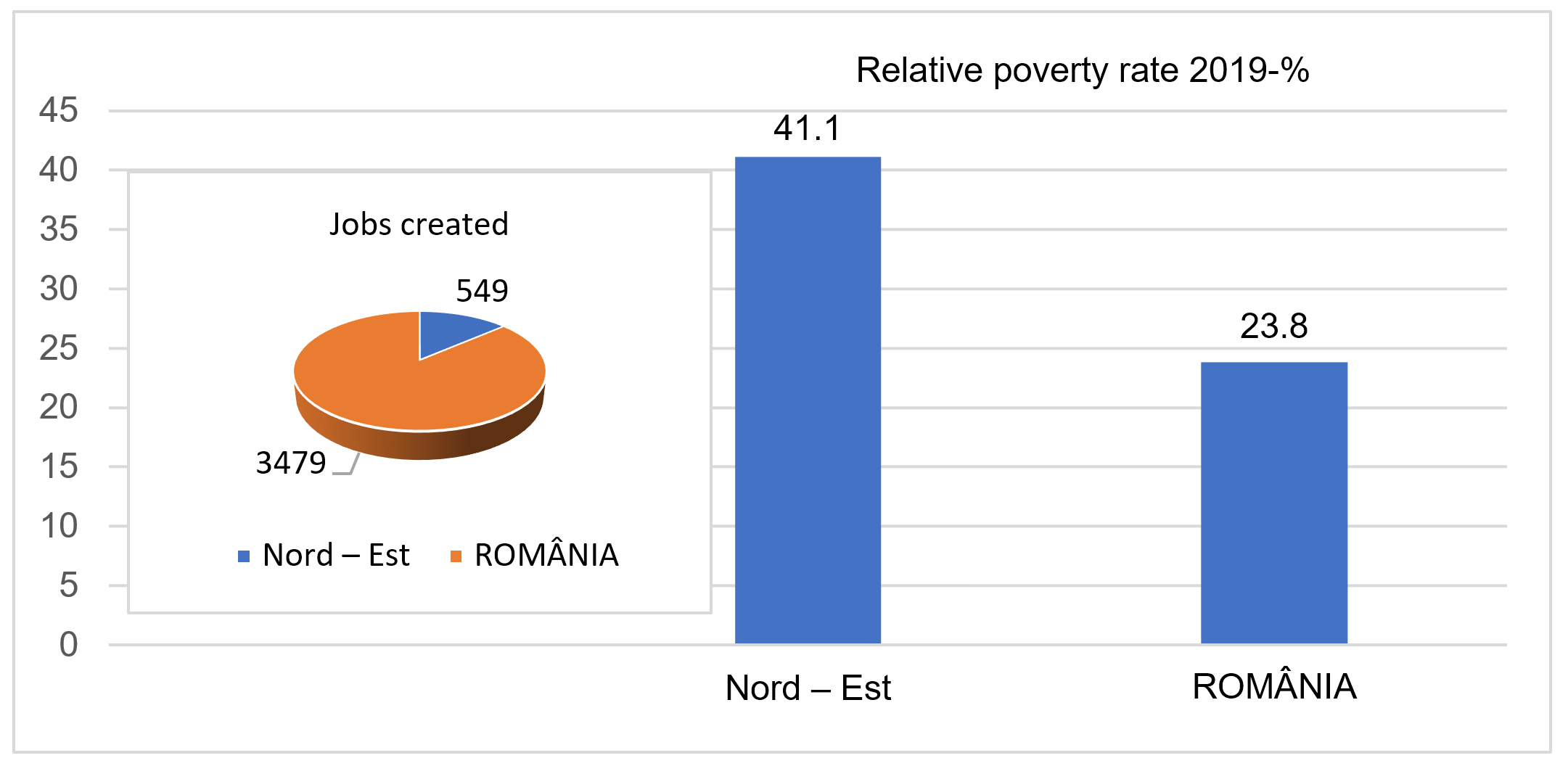

We set out to study the influence of the funding received through M19 LEADER on rural communities, poorer or richer areas, and whether they were motivated to attract funding. The relative poverty rate in Romania and the N-E Region was correlated with the number of bonused or penalised Local Action Groups, in the two bonus sessions: basic and performance, respectively, at the levels of 2019 and 2020, and was chosen as a comparison indicator.

After processing the data, the results obtained are presented below: Table 7 presents the centralised situation of the bonused and penalised LAGs and the relative poverty rate.

It would be desirable that the regions with a higher degree of poverty are more motivated to access financing to develop, but as we can see in Table 7 and Table 8, the regions with the lowest relative poverty rate are the most demotivated in attracting financing, having sufficient own resources, taking into account the North-East Development Region which can be considered the poorest.

Next, to see the influences of additional funding received by the Local Action Groups, for the year 2021, the following were studied: the relative poverty rate in 2019 and 2021, distributed by region; the number of bonused LAGs in 2021, distributed by region; the average value of SDL/LAG, in 2021, distributed by region; the average number of jobs created/GAL, distributed among regions in Romania (Table 8).

Table 8 shows, by region, the relative poverty rate in the years 2019, 2020, and 2021. Only in the West Region did this indicator increase from one year to another during the three years exemplified. In the rest of Romania’s regions, the trend was decreasing, and the North-East Development Region had the same trend—from 41.1% in 2019 to 35.6% in 2021.

According to the studies carried out, it can be established that at the level of Romania, most regions have exceeded their ceilings assumed through SDLs, such as the situation of the North-East Development Region, which has assumed 479 jobs, and until 31.01.2021 the number of positions created was 549. As the actions provided for in the SDL are implemented, until the allocated financial resources are exhausted, the total value of this indicator will increase.

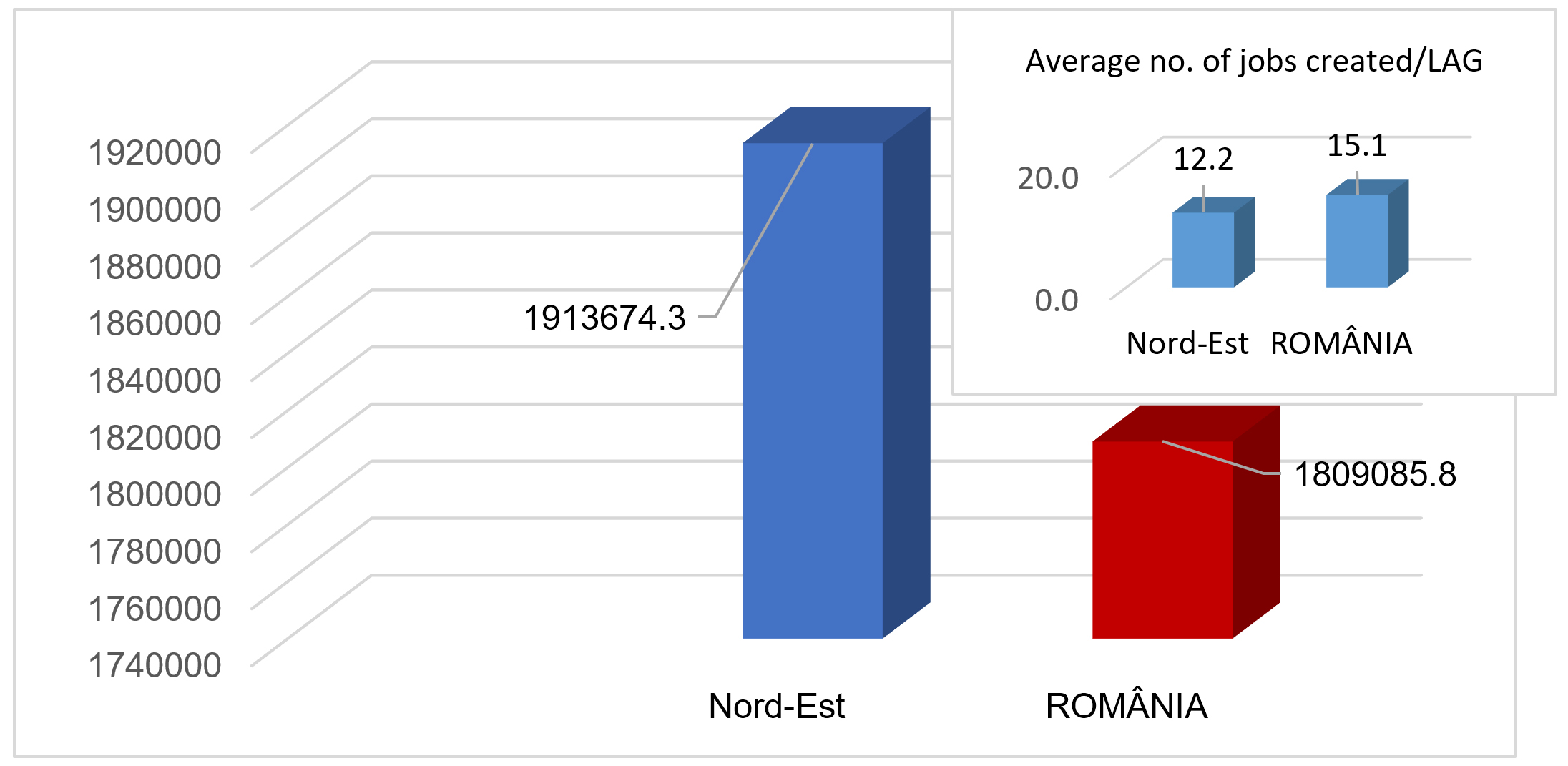

In the North-East Development Region, the average value allocated to SDL (19.2)/GAL was 1,913,674.30 euros, and the average number of jobs was only slightly influenced by the allocated values. The investments made in the territory through the funding received through M19 LEADER have led to the creation of countless jobs, a fact proven by the administrative analysis that aims to retain or attract the young population in rural areas because young people now benefit equally from living conditions as in the urban environment, noting that the funding did not really go towards improving the small infrastructure.

The rural areas analysed in the N-E region fit into a general x-ray of rural areas in Romania, where rural development was absent until the moment when their demographic, economic, and social decline was observed. This is trying to find solutions to revitalise Romanian villages, and the LEADER approach comes with its 7 principles, which propose that rural development be done in a different way.

It is important that the LEADER approach, through its implementation mechanism in Romania, the N-E Region, has beneficial effects on the eligible territory and rural development, without which the rural areas would have been poorer and deprived of possibilities. It is desirable that its effectiveness be proven in the long term, rural development should be achieved by revitalising the rural perimeter in order to reduce the existing gaps between urban and rural areas.

Next, we will try to answer the second question.

Is the LEADER programme a truly innovative approach?

In Romania, LEADER specifies the directions of action through: Axis 4 (LEADER) from PNDR 2007–2013, in the period 2007–2013; M19 (LEADER) from PNDR 2014–2020, whose applicability also extended to the transition period 2021–2022, and DR-36 (LEADER) from PNS 2023–2027.

Funding through the LEADER programme is particularly important because: it is done according to the eligible area of the Local Action Group and the number of inhabitants; it finances specific needs of the LAG, which are analysed in advance and mentioned in the SDL.

Access to financing is also allowed for entities that could not obtain financing in any other form in this way, helping the economic and social development of rural areas, reducing discrepancies between urban and rural environments, and promoting social inclusion. It is very important that the LEADER programme propose innovative activities, encourage cooperation, preserve and develop local identity, and allow exchanges of experience and good practices that can extend to the transnational level.

The Local Action Groups represent a useful programme for the economy of Romania and the N-E Region, especially for the rural environment, through which companies, together with local authorities, can discover the problems of communities and absorb European money to solve them. Local action groups (LAGs) are the ones that deal with the orientation of European funding towards the most pressing problems facing local communities. The implementation of the Local Development Strategy comes with the support of public-private actors, both through the advantages of support for economic growth and through the contribution to the sustainable development of resources in the region, the improvement of the quality of life, and the preservation of natural and cultural values.

Table 7

Bonused, penalised LAGs and relative poverty rate (2019) in Romania, North-East Region

|

No. crt. |

Region |

Total LAGs |

No. LAGs bonused |

No. LAGs penalised |

Relative poverty rate (%)* |

|

1 |

North- East |

45 |

5 |

0 |

35,60 |

|

2 |

Total |

239 |

18 |

18 |

N/A |

*Source: Processing according to data MADR (2022)

Table 8

The relative poverty rate in Romania, distributed by region

|

No. crt. |

Region |

Relative poverty rate (%)* |

||

|

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

||

|

1 |

North – East |

41.1 |

35.6 |

35.6 |

|

2 |

South – East |

31.1 |

32.6 |

30.5 |

|

3 |

South |

26 |

23.4 |

23 |

|

4 |

South -West |

31.6 |

32.7 |

30.5 |

|

5 |

West |

14.7 |

20 |

20.7 |

|

6 |

North – West |

14.7 |

15.5 |

14.1 |

|

7 |

Centre |

21.2 |

21.9 |

20.2 |

|

8 |

București-Ilfov |

2.9 |

2.4 |

2.9 |

|

9 |

Romania |

23.8 |

23.4 |

27.5 |

*Source: Processing according to data NIS (2022)

At the same time, the LEADER approach and, respectively, the implementation of the strategy come into play in solving the main objectives established based on a bottom-up approach as follows: 1. Increasing the quality of life and reducing disparities between the urban and rural environment through the development of public utility infrastructure 2. Reducing dependence on the agricultural sector of the population in the LAG territory by stimulating the business environment, otherwise contributing to the increase in the number of non-agricultural activities carried out in the LAG territory. 3. Increasing the added value of products by supporting agricultural activities and applying to quality schemes; 4. Improving the general performance of agricultural holdings by increasing the competitiveness of agricultural activity, the diversification of agricultural production, and the quality of the products obtained; 5. encouraging association and increasing producers’ incomes by restructuring small and medium-sized holdings and transforming them into commercial holdings and joint marketing of production; 6. Increasing the standard of living in the territory belonging to the LAG by preserving the traditions and crafts specific to the area, enhancing the local cultural heritage, and promoting rural tourism. 7. Use of renewable energy sources and energy efficiency 8. Fighting poverty and social exclusion by creating and/or improving social infrastructure 9. Improving the accessibility, use, and quality of information and communication technologies (ICT) (Opria et al., 2021; Pe’er et al., 2020).

From the analyses carried out, it was found that LEADER started from the premise that by applying its principles in the territory of the North-East Development Region, an added value can be obtained compared to the top-down approach to the allocation and management of funds. The LEADER programme involves local actors in making all decisions from the project stage of the local development plan, and the inhabitants of a restricted area, with their own local identity, have grouped themselves in public-private partnerships with the aim of collaborating and finding solutions to problems identified in the territory, involving all sectors at the local level with the aim of rural development.

Thus, it was found that there is a correlation between the number of LAGs bonused in 2021 and the relative poverty rate in 2021 regarding the Local Action Groups, which received performance bonuses following the fulfilment of the indicators. For the year 2021, these are represented in value in Figure 4, qualifying 61.09% of the total number of existing partnerships and, thus: 13.81% of the total number of LAGs in the North-East Development Region.

It was followed whether there is any influence of the number of LAGs that received funding as a result of the performances achieved on the relative poverty rate at the level of 2021. It was thus found that the large number of bonused LAGs had a favourable influence on the rate of relative poverty, leading to its reduction, and the large number of partnerships that met their criteria to receive funding had a beneficial influence on the poverty of the areas served.

Next, an analysis of how the poverty rate affects the number of jobs created in the region as a result of implementing the actions outlined in the SDL that are in line with the regional rural development goals is given.

Thus, in Figure 6, these variables are highlighted: the relative poverty rate taken from the database of the National Institute of Statistics, Tempo Online, at the level of 2019, and the number of jobs created until 31.01.2021 taken from the MADR reports and processed, both distributed over the North-East Development Region and Romania.

In this work, it was also studied to what extent the jobs created through the funding received through M19 LEADER in rural areas of Romania determined the increase or decrease of the relative poverty rate indicator in 2021. Table 9 highlights the values of the jobs created through the LEADER funding, on the North-East Development Region and on the whole of Romania, until 31.01.2021.

The values analysed through their influence on each other show that the poverty rate in all regions of the country led local factors to mobilise and take advantage of the funding received through M19 LEADER with the aim of improving the living standards of the inhabitants, but the time interval in which they were analysed may be too short to notice considerable improvements in the rural area. However, over 5000 jobs were created in this interval as a natural consequence of the funding received through M19 LEADER, funding without which this would not have been possible and the rural development process would have been much slowed down.

Source: Own processing after MADR (2022)

Figure 4 – LAGs qualified for additional bonusing in 2021 in the North-East Development Region compared to Romania

Source: Processing after MADR (2022)

Figure 5 – The average value of SDL/GAL and the average number of jobs created in Romania respectively, the N-E and GAL regions

Source: according to MADR (2022) and NIS (2022)

Figure 6 – Relative poverty rate (2019) and the number of jobs created on 31.01.2021, in Romania, N-E Region

Table 9

The jobs created through LEADER funding until 31.01.2021 and the relative poverty rate

|

Nr. crt. |

Region |

Relative poverty rate 2021 (%) |

Jobs created |

|

1 |

North – East |

35.60 |

684 |

|

2 |

ROMANIA |

27.5 |

5128 |

Source: Own processing after MADR (2022) and NIS (2022)

Also, the unequal number of jobs at the level of each region of Romania suggests the application of the innovative “bottom-up” principle of the LEADER approach, i.e., the sizing of the need started from the preliminary analysis of the territory and, of course, according to the financial allocation.

The data studied through the administrative analysis show the same situation: the territory of the North East Region is poor, fragmented, depopulated, or in the process of being depopulated, with few opportunities for young people.