Shawkat A. M’Sadeq, Hojeen M. Abdullah, Nabaz I. Mohammed, Fathi A. Omer, Nashwan S. Mizzouri, Amanda J. Dickson, Peter M. Hirst, Mark A. Russell

ABSTRACT. The study examined the different agriculture information channels utilized by farmers in the Nineveh Plains. A total of 308 of information sources were classified based on districts, minority groups, and age categories. A comprehensive questionnaire was prepared and covered several channels, including experienced farmers, farmer groups, extension offices, NGOs, radio, TV, newspapers, and libraries. The results of this study showed that Experienced farmers were the most dependable agriculture information source for farmers in Al-Hamdaniya, Bashiqa, and Telkaif. In Al Hamdaniya, 77.4% considered experienced farmers trustworthy, while in Bashiqa and Telkaif, percentages were 74.7% and 66.3%, respectively. Farmers from various minorities, including Turkmen (79.4%), Shabak (75.3%), Christian, Kaki (74.1%), and Yazidi (69.1%), identified experienced farmers as the predominant and trusted information source. farmers’ groups, and NGOs as source of information were significantly differed among minorities. The majority of kaki farmers (59.3%) depended on the Farmers’ group as source of information. However, 48% of Christian farmers (48.3%) received agriculture information from NGOs. Based on age categories, high percentage of interviewed farmer considered radio, TV, newspapers, libraries, extension offices, farmer groups, and NGOs as not dependable information sources. Instead, more than 68% of famers from all age group considered experienced farmers as the primary and trusted source of information.

Keywords: field crops; information sources; livestock; Nineveh Plains; vegetables; water resources.

Cite

ALSE and ACS Style

M’Sadeq, S.A.; Abdullah, H.M.; Mohammed, N.I.; Omer, F.A.; Mizzouri, N.S.; Dickson, A.J.; Hirst, P.M.; Russell, M.A. Sources of information used by the farmers in the Nineveh Plains. Journal of Applied Life Sciences and Environment 2024, 57 (3), 459-474.

https://doi.org/10.46909/alse-573147

AMA Style

M’Sadeq SA, Abdullah HM, Mohammed NI, Omer FA, Mizzouri NS, Dickson AJ, Hirst PM, Russell MA. Sources of information used by the farmers in the Nineveh Plains. Journal of Applied Life Sciences and Environment. 2024; 57 (3): 459-474.

https://doi.org/10.46909/alse-573147

Chicago/Turabian Style

M’Sadeq, Shawkat A., Hojeen M. Abdullah, Nabaz I. Mohammed, Fathi A. Omer, Nashwan S. Mizzouri, Amanda J. Dickson, Peter M. Hirst, and Mark A. RUSSELL. 2024. “Sources of information used by the farmers in the Nineveh Plains” Journal of Applied Life Sciences and Environment 57, no. 3: 459-474.

https://doi.org/10.46909/alse-573147

View full article (HTML)

Sources of Information Used by the Farmers in the Nineveh Plains

Shawkat A. M’SADEQ1, Hojeen M. ABDULLAH1, Nabaz I. MOHAMMED1, Fathi A. OMER1, Nashwan S. MIZZOURI2, Amanda J. DICKSON3, Peter M. HIRST3 and Mark A. RUSSELL3*

1Institute of Chemistry of Moldova State University, Chisinau, Republic of Moldova; e-mail: ionbulhac@yahoo.com; verzub@mail.ru

2Institute of Genetics, Physiology and Plant Protection of Moldova State University, Chisinau, Republic of Moldova; e-mail: anastasia.stefirta@gmail.com

3Institute for Research, Innovation and Technology Transfer of “Ion Creangă” State Pedagogical University, Chișinău, Republic of Moldova; e-mail: liliabrinza@mail.ru

*Correspondence: maria.cocu@sti.usm.md; mariacocu@gmail.com

Received: Oct. 04, 2023. Revised: Dec. 07, 2023. Accepted: Dec. 14, 2023. Published online: Feb. 09, 2024

ABSTRACT. The study examined the different agriculture information channels utilized by farmers in the Nineveh Plains. A total of 308 of information sources were classified based on districts, minority groups, and age categories. A comprehensive questionnaire was prepared and covered several channels, including experienced farmers, farmer groups, extension offices, NGOs, radio, TV, newspapers, and libraries. The results of this study showed that Experienced farmers were the most dependable agriculture information source for farmers in Al-Hamdaniya, Bashiqa, and Telkaif. In Al Hamdaniya, 77.4% considered experienced farmers trustworthy, while in Bashiqa and Telkaif, percentages were 74.7% and 66.3%, respectively. Farmers from various minorities, including Turkmen (79.4%), Shabak (75.3%), Christian, Kaki (74.1%), and Yazidi (69.1%), identified experienced farmers as the predominant and trusted information source. farmers’ groups, and NGOs as source of information were significantly differed among minorities. The majority of kaki farmers (59.3%) depended on the Farmers’ group as source of information. However, 48% of Christian farmers (48.3%) received agriculture information from NGOs. Based on age categories, high percentage of interviewed farmer considered radio, TV, newspapers, libraries, extension offices, farmer groups, and NGOs as not dependable information sources. Instead, more than 68% of famers from all age group considered experienced farmers as the primary and trusted source of information.

Keywords: field crops; information sources; livestock; Nineveh Plains; vegetables; water resources

INTRODUCTION

The Nineveh Plains, the northern part of Iraq, is considered the “breadbasket” of Iraq. It has rich and fertile land and is recognized for its paramount importance for local poultry breeds, broilers, vegetables, and field crops. Throughout history, this region has consistently served as a productive agricultural area, playing a pivotal role in contributing substantially to Iraq’s overall food production (M’Sadeq et al., 2023). The historical emphasis on agriculture on the Nineveh Plains indicates a deep-rooted foundation of farming expertise within the local population. This wealth of agricultural knowledge is not limited to crop cultivation alone, but extends to animal husbandry.

Access to agricultural information is crucial for effectively engaging with other production parts. It can empower farmers by giving them control over their resources and decision-making processes (Dolinska and d’Aquino, 2016). Farmers may make better decisions and are more effective overall with access to information. Possessing control over vital information leads directly to farmers’ empowerment. This empowerment includes agricultural production, processing, trade, and marketing decision-making. A well-organized system for distributing information is crucial in helping farmers make informed decisions regarding the importance of agricultural activity in Nineveh Plains. The system needs to be both effective and efficient. Offering new information technology services as a support system for farmers, enabling them to negotiate their difficulties confidently.

This improvement enhances farmers’ ability to optimize agriculture production, processing methods, trading practices, and strategic marketing decisions (Cereno, 2023). It is important to remember that research institutions, educational initiatives, and farming organizations all work together to help farmers. They provide important information and support, which helps farmers make better decisions. As Usman et al. (2021) suggested, providing farmers with the required knowledge enhanced their agricultural practices. Researchers, educators, and agricultural associations provide farmers with information that gives farmers a beneficial understanding of a range of farming topics, such as methods, environmentally friendly practices, and market trends.

Agriculture information available in research institutions, universities, and public offices is an important resource for the agricultural industry (Omulo and Kumeh, 2020). However, rural farmers in developing countries face a substantial challenge due to the limited accessibility of agricultural information (Naika et al., 2021). This highlights the weak links between research, extension services, and farmers, which hinders knowledge dissemination and weakens relationships between research institutions, extension services, and farmers. This lack of communication and collaboration limits the transfer of knowledge and prevents farmers from using new technologies to improve farming, especially in developing countries (Dhillon and Moncur, 2023). In order to effectively address this situation, it is necessary to strengthen the network of connections and communication channels that exist between research organizations, extension agencies, and farmers.

This study investigated agriculture, local poultry breeds, broilers, ruminants, vegetables, and field crop production, information sources used by farmers in the Nineveh Plains. The study investigated Nineveh Plains farmers’ agricultural information-seeking activities to help create more targeted and effective agricultural extension initiatives. Understanding farmers’ preferences and challenges in accessing agriculture information which is crucial to optimizing agricultural knowledge delivery and promoting new technology adoption in the region.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study site

This study was conducted in Al-Hamdaniya, Bashiqa, and Telkaif districts in the Nineveh Plains, the northern part of Iraq. The Nineveh Plains region is located to the east and northeast of Mosul, one of the most important cities in Iraq. The coordinates for Al-Hamdaniya are 36° 16′ 15.35″ N latitude and 43° 22′ 39.29″ E longitude. Bashiqa’s coordinates are 36.45046° N latitude, 43.34977° E longitude, and Telkaif’s coordinates are 36.5922° N latitude, 43.0621° E longitude.

Data collection

Data of this study were collected from July 2022 to July 2023 through direct interviews with farmers in selected villages. A comprehensive questionnaire was employed as the primary data collection method. The questionnaire consisted of different aspects of agricultural information sources for local poultry breeds, broilers, sheep, cow, vegetable, and field crop production. The data collection grouped by districts (Al-Hamdaniya, Bashiqa, and Telkaif), minorities (Christian, Kaki, Shabak, Turkmen, and Yazidi), and age groups (less than 25 years, 26-35 years, 36-45 years, and more than 45 years). This study included different agricultural information channels, such as radio, TV, newspapers, libraries, extension offices, farmer groups, experienced farmers, and NGOs. Experts at the University of Duhok extension staff validated the interview survey instrument.

A random sampling procedure was used to ensure the collected data was representative. In the Nineveh Plains region, 27 villages were randomly selected ( nine villages were selected for each district).

The sample sizes (N) for each district varied based on factors such as security, minority population, farmers’ age, geography, and time constraints. For Al-Hamdaniya, the sample size was 159; for Bashiqa, it was 75; and for Telkaif, it was 74 (A total of 308 respondents). The sample sizes for minorities were as follows: Christian 58, Kaki 54, Shabak 106, Turkmen 34, and Yazidi 55(A total of 307 respondents). One questionnaire was excluded from the analysis due to the presence of illogical responses provided by minority respondents. Regarding age categories for all three districts, the sample sizes were less than 25 years (17), 26-35 years (33), 36-45 years (80), and more than 45 years (178) (A total of 308 respondents). Based on their scores, the farmers were divided into four categories with equal ranges for each group: No preference group (0-25), low preference group (26-50), medium preference group (51-75), and high preference group (scores above 75).

Statistical Analysis

The data collected were statistically analyzed using the SPSS program (SPSS, 2019). The data were non-normally distributed (Shapiro test ~ P<0.05); therefore, they were transformed using the cube method within the same program.

The Chi-square test and frequency analysis were performed according to district, religion and age category.

RESULTS

Farmer agriculture information sources based on districts

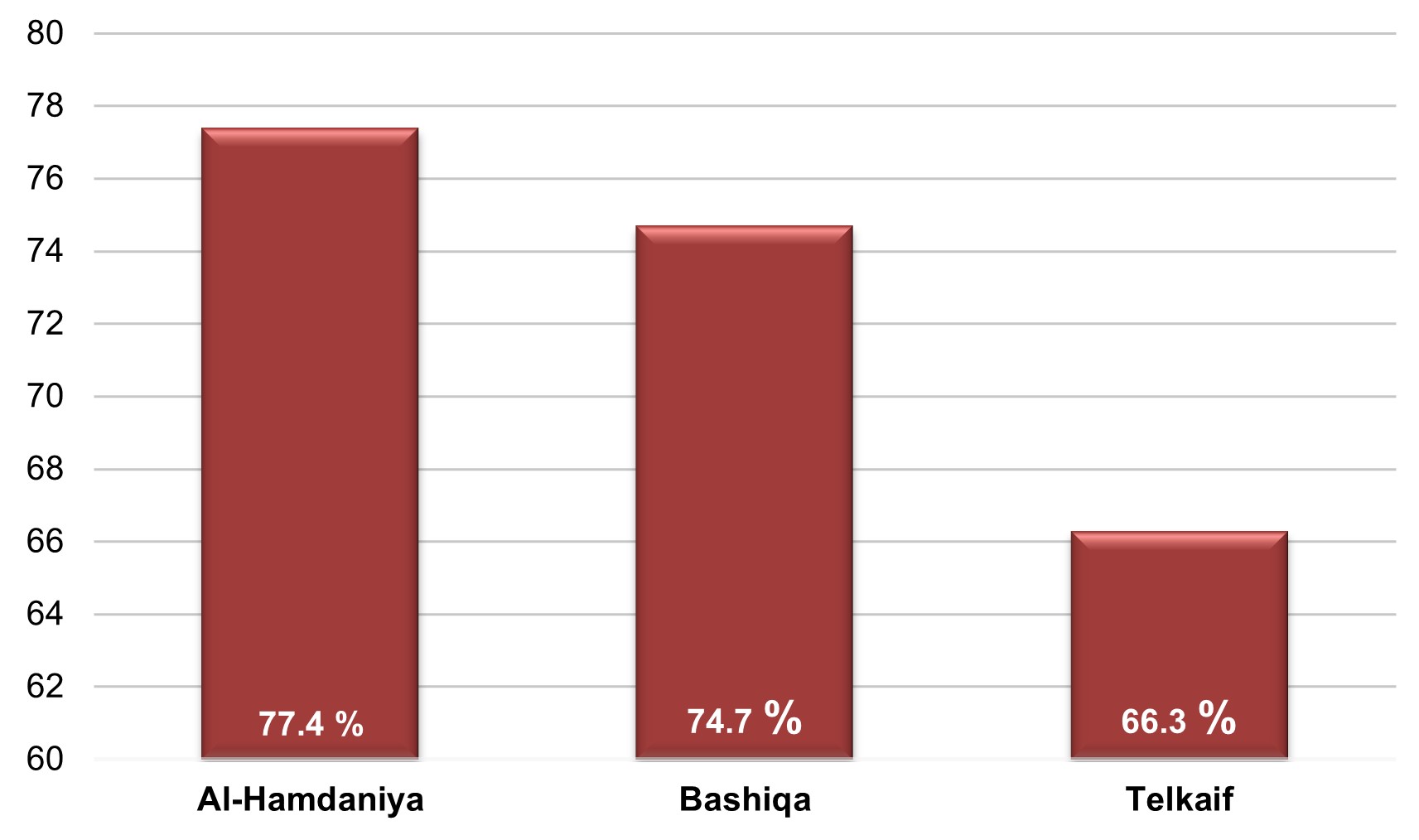

The response frequencies and percentages of the information sources studied in the three surveyed districts are presented in Table 1 and Figure 1.

The primary information source deemed adequate by farmers in the selected districts was experienced farmers. Specifically, in Al-Hamdaniya, 77.4% of respondents considered experienced farmers a reliable source, while in Bashiqa and Tellkaif, these percentages stood at 74.7% and 66.3%, respectively (Figure 1). On the contrary, various information sources and services received lower ratings, including radio, TV, newspapers, libraries, extension offices, farmer groups, experienced farmers, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) (Table 1).

The statistical analysis revealed significant differences between the observed and expected proportions of information sources across the three districts, particularly for Radio, TV, Newspapers, and Farmer’s group (p < 0.01). Specifically, in Al Hamdaniya, 16.61% of farmers utilized radio, 17.61% relied on TV, and 16.95% turned to newspapers for agricultural information. In Bashiqa, 21.33% accessed agricultural information through radio, 21.33% through TV, and 25.33% through newspapers. Conversely, in Tellkaif, radio was used by 8.11% of farmers, TV by 10.81%, and newspapers by 10.80%. Furthermore, the role of farmer groups as a source of agricultural information exhibited significant variation among the districts, with 50.4% of farmers in Al Hamdaniya, 50.66% in Bashiqa, and 14.86% in Tellkaif.

Farmer agriculture information sources based on minorities

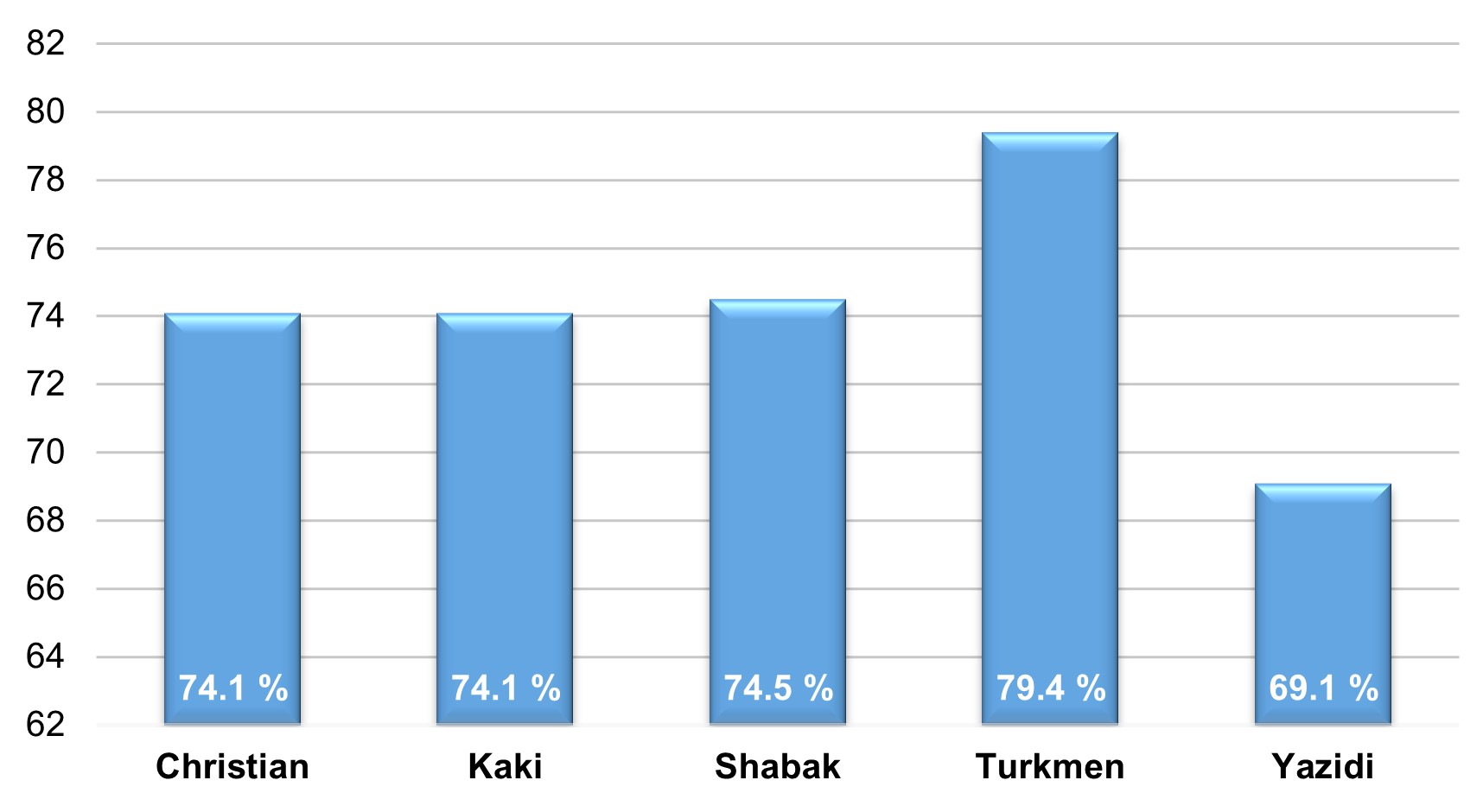

The agriculture information sources for farmers within the Nineveh Plains minorities, including Christian, Kaki, Shabak, Turkmen, and Yazidi communities, were investigated and documented in Table 2 and Figure 2.

It became evident that farmers belonging to these diverse groups did not rely on conventional channels such as radio, TV, newspaper, library, extension office, farmers’ groups, and NGOs to obtain agricultural information.

Contrastingly, the predominant and trusted information source among farmers from various minorities was identified as experienced farmers. Specifically, when examining different minority groups, 79.4% of Turkmen respondents regarded experienced farmers as a dependable source of agricultural information.

Table 1

Comparisons of agriculture training and source of information among Al-Hamdaniya, Bashiqa and Telkaif districts

|

Source of Information |

District no (%) |

P value |

||

|

Al-Hamdaniya |

Bashiqa |

Telkaif |

||

|

n=159 (%) |

n=75 (%) |

n=74 (%) |

||

|

Radio No Low Medium High |

90 (56.60) 41 (25.79) 27 (16.98) 1 (0.63) |

31 (41.33) 28 (37.33) 12 (16.00) 4 (5.33) |

27 (36.49) 41 (55.41) 6 (8.11) 0 (0.00) |

<0.001 |

|

TV No Low Medium High |

89 (55.97) 42 (26.42) 27 (16.98) 1 (0.63) |

32 (42.70) 27 (36.00) 13 (17.33) 3 (4.00) |

23 (31.08) 43 (58.11) 7 (9.46) 1 (1.35) |

<0.001 |

|

Newspaper No Low Medium High |

90 (56.60) 42 (26.42) 26 (16.35) 1 (0.60) |

33 (44.00) 23 (30.67) 16 (21.33) 3 (4.00) |

38 (51.35) 28 (37.84) 8(10.80) 0 (0.00) |

0.005 |

|

Library No Low |

159 (100.00) 0 (0.0000) |

74 (98.70) 1 (1.30) |

74(100.00) 0 (0.00) |

0.210 |

|

Extension office No Low Medium High |

83 (52.20) 47 (29.56) 25 (15.72) 4 (2.52) |

32 (42.67) 23 (30.70) 15 (20.00) 5 (6.73) |

37 (50.00) 25 (33.78) 12 (16.22) 0 (0.00) |

0.263 |

|

Farmers’ Group No Low Medium High |

48 (30.20) 42 (26.40) 37 (23.30) 32 (20.10) |

18 (24.00) 19 (25.33) 25 (33.33) 13 (17.33) |

41 (55.41) 22 (29.73) 11 (14.86) 0 (0.00) |

<0.001 |

|

Experienced Farmers No Low Medium High |

7 (4.4) 29 (18.2) 33 (20.8) 90 (56.6) |

1 (1.30) 18 (24.00) 20 (26.70) 36 (48.00) |

3 (4.1) 22 (29.7) 11(14.9) 38 (51.4) |

0.256 |

|

NGOs No Low Medium High |

83 (52.2) 40 (25.2) 25 (15.7) 11 (6.9) |

31 (41.3) 31 (41.3) 10 (13.3) 3 (4.0) |

27 (36.5) 32 (43.2) 13 (17.6) 2 (2.7) |

0.054 |

Chi-squared test was performed for statistical analyses. Significant differences

Similarly, among Shabak farmers, the percentage was 75.3%, while Christian, Kaki, and Yazidi farmers reported percentages of 74.1%, 74.1%, and 69.1%, respectively (Figure 2). The statistical analysis revealed differences between the observed and expected proportions of information sources among the various minorities, with a particular emphasis on farmers’ groups and NGOs reaching statistical significance (p < 0.01) (Table 2). Mainly, Kaki farmers exhibited a significant reliance on farmers’ groups, with 59.3% depending on this source for agricultural information, followed by Yazidi farmers at 47.2%. In contrast, Christian, Shabak, and Turkmen farmers reported lower percentages, relying on farmers’ groups as sources for agriculture information at 28.6%, 34.2%, and 20.6%, respectively.

Figure 1 – Farmer’s percentages response to experienced farmers as a significant information source, based on district

Figure 2 – Farmer’s percentages responses to the experienced farmers as primary information sources based on minorities

Table 2 – Comparisons of agriculture training and sources of information among the minorities of farmers

|

Source of Information |

Religion no (%) |

P value |

||||

|

Christian |

Kaki |

Shabak |

Turkmen |

Yazidi |

||

|

n=58 (%) |

n=54(%) |

n=106 (%) |

n=34 (%) |

n=55 (%) |

||

|

Radio No Low Medium High |

24 (41.4) 22 (37.9) 12 (20.7) 0 (0.0) |

30 (55.6) 14 (25.9) 9 (16.7) 1 (1.9) |

57 (53.8) 37 (34.9) 9 (8.5) 3 (2.8) |

17 (50.00) 12 (35.3) 5 (14.7) 0 (0.00) |

19 (34.5) 25 (45.5) 10 (18.2) 1 (1.8) |

0.283 |

|

TV No Low Medium High |

20 (34.5) 23 (39.7) 14 (24.1) 1 (1.7) |

29 (53.7) 15 (27.8) 9 (16.7) 1 (1.9) |

58 (54.7) 36 (34) 10 (9.4) 2 (1.9) |

17 (50.0) 13 (38.2) 4 (11.8) 0 (0.00) |

19 (34.5) 25 (45.5) 10 (18.2) 1 (1.8) |

0.240 |

|

Newspaper No Low Medium High |

28 (48.5) 18(31.0) 12 (20.7) 0 (0.00) |

29 (53.7) 14 (25.9) 10 (18.5) 1 (1.9) |

56 (52.8) 35 (33.0) 12 (11.3) 3 (2.8) |

19 (55.9) 14 (41.2) 1 (2.9) 0 (0.0) |

28 (50.9) 16 (29.1) 11 (20.0) 0 (0.0) |

0.381 |

|

Library No Low |

58 (100.0) 0 (0.00) |

54 (100.0) 0 (0.00) |

106 (100)0 (0.00) |

34 (100.0) 0 (0.00) |

54 (98.2) 1 (1.8) |

0.331 |

|

Extension office No Low Medium High |

27 (46.6) 15 (25.9) 16 (27.6) 0 (0.00) |

27 (50.0) 16 (29.6) 8 (14.8) 3 (5.6) |

52 (49.1) 39 (36.8) 11 (10.4) 4 (3.8) |

18 (52.9) 13 (38.2) 3 (8.8) 0 (0.0) |

27 (49.1) 12 (21.8) 14 (25.5) 2 (3.6) |

0.097 |

|

Farmers’ Group No Low Medium High |

30 (51.7) 11 (19.0) 16 (27.6) 1 (1.7) |

7 (13.0) 15 (27.8) 11 (20.4) 21 (38.9) |

39 (36.8) 31 (29.2) 23 (21.9) 13 (12.3) |

13 (38.2) 14 (41.2) 5 (14.7) 2 (5.9) |

17 (30.9) 12 (21.8) 18 (32.7) 8 (14.5) |

<0.0001 |

|

Experienced Farmers No Low Medium High |

4 (6.90) 11 (19.0) 14 (24.1) 29 (50.0) |

3 (5.60) 11 (20.40) 10 (18.5) 30 (55.6) |

1 (0.90) 26 (24.5) 18 (17.0) 61 (57.5) |

0 (0.00) 7 (20.6) 6 (17.6) 21 (61.8) |

3 (5.5) 14 (25.4) 16 (29.1) 22 (40) |

0.365 |

|

NGOs No Low Medium High |

8 (13.8) 22 (37.9) 19 (32.8) 9 (15.5) |

42 (77.8) 5 (9.3) 5 (9.3) 2 (3.7) |

46 (43.4) 44 (41.5) 11 (10.4) 5 (4.7) |

22 (46.7) 11 (32.4) 1 (2.9) 0 (0.0) |

23 (41.8) 20 (36.4) 12 (21.8) 0 (0.0) |

<0.0001 |

Chi-squared test was performed for statistical analyses. Significant differences

Farmer agriculture information sources based on age categories

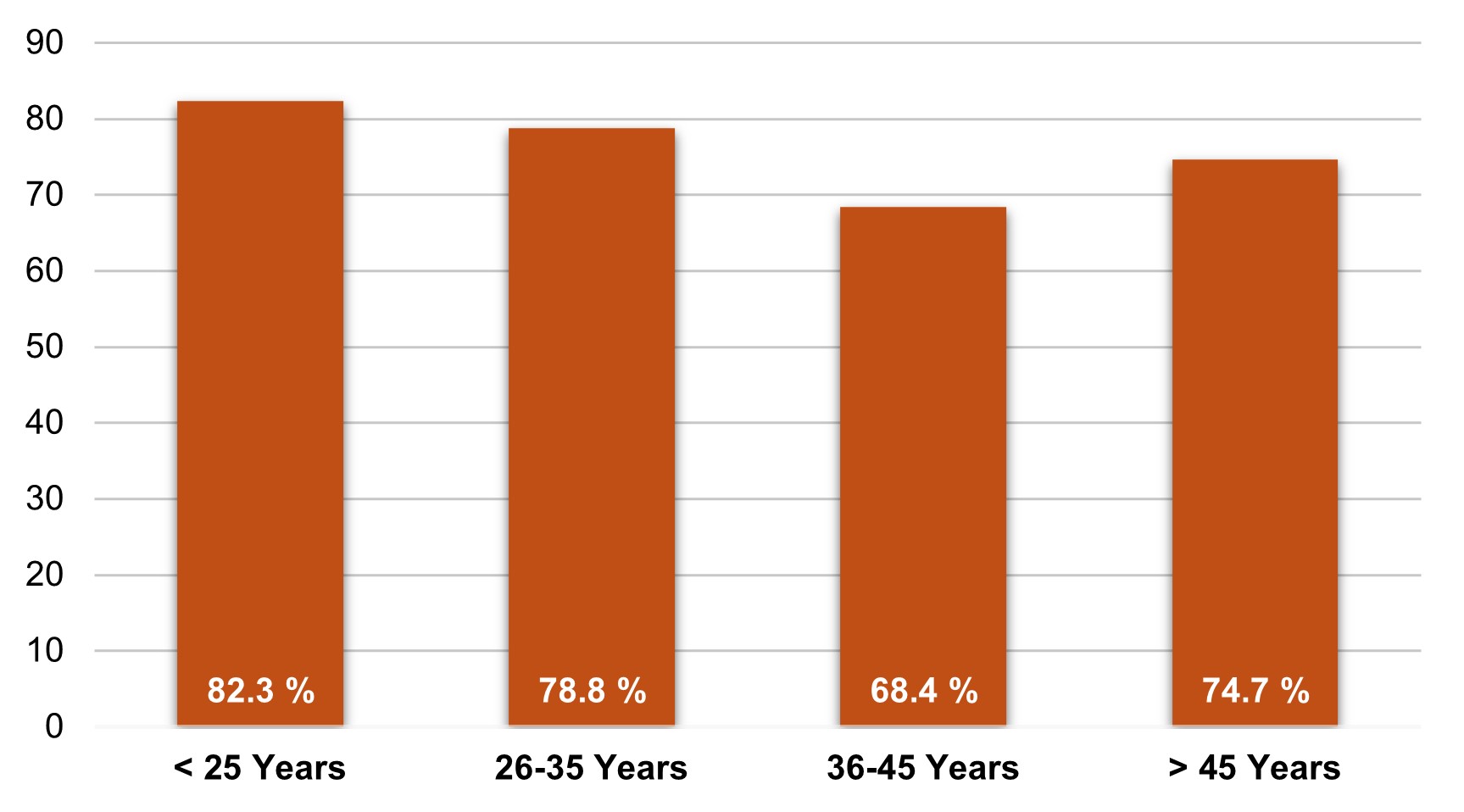

The relationship between age and the sources individuals use to gather information about agriculture was examined by considering age as a factor reflecting experience, wisdom, and openness to new experiences. Table 3 and Figure 3 demonstrate a notable lack of interest in utilizing the library as a source of information across all age groups of farmers. The lack of interest in the library as a source of agricultural information among farmers of all age groups could stem from an underdeveloped or unavailable library infrastructure. The difference between observed and expected proportions was highly significant (p < 0.01) (Table 3). Farmers across diverse age categories did not rely heavily on traditional channels like radio, TV, newspapers, libraries, extension offices, farmers’ groups, and NGOs to access agricultural information. The data revealed a clear association between age categories and the utilization of extension offices as a source of agricultural information. As age increased, there was a corresponding rise in the reliance on extension offices. Specifically, the percentages of farmers utilizing extension offices for agricultural information were 5.9% for those below 25 years, 12.1% for the 25-35 age group, 19% for the 36-45 age group, and the highest at 23% for those above 45 years. However, the primary and trusted source of information among farmers of varying age groups was identified as experienced farmers. In different age groups, it was found that among farmers below 25 years, an impressive 82.3% considered experienced farmers a reliable source of agricultural information. Similarly, for farmers aged between 25-35, 36-45, and those above 45 years, the percentages stood at 78.8%, 68.4%, and 74.4%, respectively (Figure 3), in their belief that experienced farmers were a reliable source of agricultural information.

Figure 3 – Farmer’s percentages response to the experienced farmers as a significant information source based on age category

Table 3

Comparisons of agriculture training and sources of information across different farmer age groups

|

Source of Information |

Age Groups (%) |

P value |

|||

|

<25 Years |

26<35 Years |

36<45 Years |

>45 Years |

||

|

n=17 (%) |

n=33 (%) |

n=80 (%) |

n=178 (%) |

||

|

Radio No Low Medium High |

8 (47.10) 6 (35.30) 2 (11.80) 1 (5.90) |

20 (60.60) 10 (30.30) 2 (6.10) 1 (3.00) |

34 (42.50) 31 (38.80) 14 (17.50) 1 (1.30) |

86 (48.30) 63 (35.40) 27 (15.20) 2 (1.10) |

0.614 |

|

TV No Low Medium High |

9 (52.90) 6 (35.30) 2 (11.80) 0 (0.00) |

20 (60.60) 11 (30.30) 1 (3.00) 1 (3.00) |

31 (39.20) 32 (40.50) 14 (17.70) 2 (2.50) |

83 (46.60) 63 (35.40) 30 (16.90) 2 (1.10) |

0.507 |

|

Newspaper No Low Medium High |

8 (47.10) 6 (35.30) 2 (11.80) 1 (5.90) |

20 (60.60) 11 (30.30) 1 (3.00) 1 (3.00) |

35 (44.30) 31 (39.20) 12 (15.20) 1 (1.30) |

97 (54.50) 49 (27.50) 31 (17.40) 1 (0.60) |

0.193 |

|

Library No Low |

16 (94.10) 1 (5.90) |

33 (100.00) 0 (0.00) |

79 (10.00) 0 (0.00) |

178 (100.00) 0 (0.00) |

0.001 |

|

Extension office No Low Medium High |

10 (58.80) 6 (35.30) 0 (0.00) 1 (5.90) |

20 (60.60) 9 (27.30) 3 (9.10) 1 (3.0) |

35 (44.30) 31 (39.20) 13 (16.50) 2 (2.50) |

88 (49.40) 49 (27.50) 36 (20.20) 5 (2.80) |

0.309 |

|

Farmers’ Group No Low Medium High |

3 (17.60) 7 (41.20) 4 (23.50) 3 (17.60) |

11 (33.30) 6 (18.20) 11 (33.30) 5 (15.20) |

21 (26.60) 28 (35.40) 13 (16.50) 17 (21.50) |

71 (39.90) 42 (23.60) 45 (25.30) 20 (11.20) |

0.054 |

|

Experienced Farmers No Low Medium High |

0 (0.00) 3 (17.60) 4 (23.50) 10 (58.80) |

0 (0.00) 7 (21.20) 6 (18.20) 20 (60.60) |

2 (2.50) 23 (29.10) 12 (15.20) 42 (53.20) |

9 (5.10) 36 (20.20) 42 (23.60) 91 (51.10) |

0.546 |

|

NGOs No Low Medium High |

8 (47.10) 5 (29.40) 4 (23.50) 0 (0.00) |

19 (57.60) 11 (33.30) 3 (9.10) 0 (0.00) |

34 (43.0) 30 (38.00) 11 (13.90) 4 (5.10) |

80 (44.90) 56 (31.50) 30 (16.90) 12 (6.70) |

0.612 |

Chi-squared test was performed for statistical analyses. Significant differences

Correlation analysis between information sources

Comprehensive correlation analysis, detailed in Table 4, revealed intriguing patterns within the relationships among various information sources. Significantly, all the information sources demonstrated a substantial and noteworthy association with each other, marked by a level of statistical significance at p < 0.01. However, a notable exception was observed in the case of the library source, which lacked a significant correlation with any other source, suggesting a distinct independence or disconnect in its influence on farmers’ responses.

The predominant trend observed in most correlation coefficients is their optimistic temperament, indicating a simultaneous positive effect. When one information source influences a farmer’s response, the correlated source also impacts the same direction. This positive correlation was particularly evident in instances such as between radio, TV, newspaper, extension office, and farmers’ groups. The correlation coefficients within this cluster range from 0.34 to 0.91, highlighting a cohesive and harmonious influence among these sources.

Contrastingly, significant negative coefficients were observed, particularly in associations involving experienced farmers and all other sources. This suggests that the role of experienced farmers deviates substantially from the average, negatively influencing the overall information network. The coefficients in these cases range from 0.21 to 0.42, indicating a contrary impact compared to the more positive relationships observed among other sources. This pattern of correlations underscored the complexity of information dynamics within the agricultural context. It emphasizes the interrelationships of specific information sources, and the distinguishing and potentially divergent role experienced farmers play in shaping farmers’ responses. Understanding these intricate relationships is crucial for developing targeted and effective agricultural communication and extension program strategies.

DISCUSSION

Previous research examined the knowledge and information sources utilized by information seekers in rural areas of developing countries. It revealed a preference among residents for obtaining information from informal rather than formal sources (Lwoga et al., 2010).

Table 4

Correlation analysis between the information sources

|

|

Radio |

TV |

Newspaper |

Library |

Extension office |

Farmers’ Group |

Experienced Farmers |

NGOs |

||

|

Spearman’s rho |

Radio |

|

1.000 |

.906** |

.851** |

-.056 |

.784** |

.337** |

-.394** |

.209** |

|

TV |

|

.906** |

1.000 |

.807** |

-.057 |

.747** |

.288** |

-.396** |

.232** |

|

|

Newspaper |

|

.851** |

.807** |

1.000 |

-.052 |

.808** |

.352** |

-.421** |

.251** |

|

|

Library |

|

-.056 |

-.057 |

-.052 |

1.000 |

-.055 |

.048 |

-.029 |

.079 |

|

|

Extension office |

|

.784** |

.747** |

.808** |

-.055 |

1.000 |

.430** |

-.367** |

.229** |

|

|

Farmers’ Group |

|

.337** |

.288** |

.352** |

.048 |

.430** |

1.000 |

-.051 |

.025 |

|

|

Experienced Farmers |

|

-.394** |

-.396** |

-.421** |

-.029 |

-.367** |

-.051 |

1.000 |

-.209** |

|

|

NGOs |

|

.209** |

.232** |

.251** |

.079 |

.229** |

.025 |

-.209** |

1.000 |

|

**. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed)

Besides seeking information from non-governmental organizations, most farmers primarily depend on experienced farmers (Kaniki, 2001). Additional research by Meitei and Devi (2009) and Momodu (2002) indicated that farmers predominantly rely on informal networks and, to a lesser extent, mass media such as radio, television and newspapers to satisfy their information needs.

This data suggests a notable preference toward experienced farmers as more accessible resources for farmers in the surveyed areas. The implications of this disparity were significant, pointing toward a need for attention and improvement in the availability of diverse information channels. While experienced farmers were valued for their knowledge, diversifying the sources of information could enhance the overall support system for farmers (Bellon et al., 2020).

Strategies may include strengthening existing agricultural extension services, exploring innovative ways to disseminate information through media, and fostering community-based initiatives with the involvement of NGOs (Madan and Maredia, 2021). Additionally, incorporating technology-driven solutions could contribute to bridging the existing information gap, ensuring farmers have access to a well-rounded set of resources to improve their agriculture (Dutta and Anand, 2023; Ragasa, 2020).

These findings not only underscored the diversity in media channel preferences, but also highlighted the crucial role of farmer groups in some regions as significant sources of agricultural information. These differences underscore the diverse information-seeking patterns among farmers in these three districts. The findings indicated that farmers from different districts encounter challenges such as infrastructure shortages, particularly power, and issues related to radio and service fees.

The study similarly highlights the absence of locally specified information and inadequate knowledge and skills regarding how and where to access the required information.

The findings of this study were corroborated by the research conducted by Tiwari (2022), Cieslik et al., (2021), and Ireri et al., (2021). Their studies similarly demonstrated that numerous developing countries experience challenges related to a lack of infrastructure and shortcomings in government service delivery. This collective body of research reinforces that the insufficiency of infrastructure and deficiencies in government-provided services are prevalent issues in many developing nations.

The agriculture information sources for farmers within the Nineveh Plains minorities, including Christian, Kaki, Shabak, Turkmen, and Yazidi communities, were investigated and documented. The results show that these farmers predominantly trust and seek information from their community members, suggesting a strong bond and reliance on traditional agricultural practices within the Nineveh Plains region. Experienced farmers within these minority communities likely possess insights and practical wisdom directly applicable to the local context. They understand the nuances of the land, climate, and specific farming techniques that work best in their region (M’Sadeq et al., 2023). Additionally, they may share knowledge about traditional or culturally significant farming practices passed down through generations.

This reliance on experienced farmers as a predominant and trusted information source is a testament to the importance of community-based knowledge-sharing in agriculture (Kommey and Fombad, 2023). The utilization of NGOs as an agriculture information source also displayed significant differences among the minorities. A total of 48.3% of Christian farmers obtained agricultural information from non-governmental organizations (NGOs). Christian farming communities exhibited information-seeking behavior that was in contrast to other minorities.

The results of this study also highlighted the preferences and differences in agriculture information sources among the studied minorities, markedly concerning the roles of farmers’ groups and NGOs. Community-specific factors played an important role in substantial variation in reliance on these sources (Mayfield-Smith, 2021). Stronger networks and more successful outreach initiatives designed by Christian NGOs for Christian rural communities may be the cause of this trend. The higher proportion can be attributed to the greater accessibility of resources, such as training programs and workshops offered by non-governmental organizations. Christian farmers will likely have more faith in the NGOs working in their areas. This leads to higher involvement and dependence on these organizations for agricultural guidance.

Furthermore, tailoring NGO agricultural initiatives to meet Christian farmers’ specific needs and preferences might increase their inclination to seek knowledge from these sources. Understanding these differences can contribute to more tailored and effective agricultural extension programs and interventions within each minority community.

A lack of interest in utilizing the library as a source of information across all age groups of farmers was noted in this study.

To address these challenges and encourage farmers to utilize the library as a valuable source of agriculture information, it’s essential to invest in improving library infrastructure, expanding the agriculture-related collection, enhancing accessibility through outreach programs and technology initiatives, and developing partnerships with agricultural organizations and extension services (Akama, 2023; Henzel et al., 2006). By actively engaging with the farming community and addressing their specific information needs, libraries can become indispensable resources for agricultural knowledge, location of farmer meetings, and support for farmers in their endeavors.

Farmers across diverse age categories did not rely heavily on traditional channels like radio, TV, newspapers, libraries, extension offices, farmers’ groups, and NGOs to access agricultural information. These findings underscored a consistent pattern of trust in the knowledge and practical wisdom shared by experienced farmers, regardless of the farmers’ age. Experienced farmers in the Nineveh Plains served as reliable sources of information for farmers of all ages for many reasons. These factors included trust, the practical applicability of their advice, personal relationships, a deep understanding of local conditions, and their history of effective agricultural methods.

The agriculture information sources vary between age categories (Bourhrous et al., 2022; King and Kay, 2020). Farmers aged under 25 years old used farmer groups as a source of agricultural information at a rate of 41.1%. For farmers under ages 25-34 and 35-45, 38% used farmer groups as a source of agriculture information, and this rate decreased to 36% for farmers aged above 45.

This implied that there might be a relationship between age and the predisposition of younger farming demography to prefer farmer groups as a source of agricultural information.

Additionally, the data revealed a clear association between age categories and the utilization of extension offices as a source of agricultural information. This indicated a progressive increase in the preference for extension services among older farmers within the surveyed age groups.

The findings of Sennuga et al. (2020) suggested that smallholder farmers in sub-Saharan African communities have an unfavorable perception of the effectiveness of agricultural extension agents. A significant majority (89%) of these farmers identified the lack of regular contact with extension agents as a significant challenge. Likewise, most smallholders expressed dissatisfaction with the effectiveness of extension services.

CONCLUSIONS

The study examined farmers’ information sources on broilers, local poultry breeds, cattle, vegetables, and field crops in selected Nineveh Plains districts to reveal demographic preferences in information-seeking. The results showed that farmers did not trust radio, TV, newspapers, libraries, extension offices, farmer groups, and NGOs as sources of information. Experienced farmers were the most trusted agricultural information source in all districts. Across ages and minorities, farmers preferred experienced farmers who demonstrated their reliability and integrity. However, radio, TV, newspapers, and farmer groups had considerable disparities in information source preferences. The survey also found that farmers of all ages were less likely to use libraries for agricultural information, potentially due to infrastructural or availability issues. The study underscores the critical role of experienced farmers as the primary and trusted source of agricultural information among farmers in the examined districts, transcending age, ethnicity, and traditional information channels. Future research should investigate the impact of digital media and assess the efficacy of diverse information sources, including both conventional and digital channels. Research needs to determine geographical differences, demographic variables, and infrastructure obstacles impacting information accessibility. Furthermore, examining the function of extension offices and peer networks and evaluating novel communication tactics could provide knowledge to improve agricultural communication and assistance.

Author Contributions: Methodology: SAM’S, HMA, NIM, FAO; Writing – original draft preparation: SAM’S, HMA, NIM, FAO; Review and editing: NSM, MAR, AJD; PMH. All authors declare that they have read and approved the publication of the manuscript in this present form.

Funding: USAID has funded this project through the LASER PULSE under TE Prime Award No: AID-7200AA18CA00009 and Subaward No: 203776UD.

Acknowledgments: The “Traditional Cultural Practices in Northern Iraq” project has been funded by USAID through the LASER PULSE, with the University of Notre Dame as the lead institution. This project studies the challenges of the food sector as it seeks solutions for tomorrow. It covers field crops, animal production, agricultural, and extension systems that are important to the ethnic and religious minorities in the Nineveh Plains region.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

Akama, Y.N. Resource Mobilization for Promotion of Sustainable Agriculture in Public Libraries: Case of the Partnership Between Kenya National Library Service and National Farmers Information Service. PhD Thesis, University of Nairobi, 2023.

Bellon, M.R.; Kotu, B.H.; Azzarri, C.; Caracciolo, F. To diversify or not to diversify, that is the question. Pursuing agricultural development for smallholder farmers in marginal areas of Ghana. World Development. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.104682.

Bourhrous, A.; Fazil, S.; O’Driscoll, D. Post-Conflict Reconstruction in the Nineveh Plains of Iraq: Agriculture, Cultural Practices and Social Cohesion. 2022.

Cereno, J. Digital agri-extension for all. Department of Social Sciences, Wageningen University, 2023.

Cieslik, K.; Cecchi, F.; Damtew, E.A.; Tafesse, S.; Struik, P.C.; Lemaga, B.; Leeuwis, C. The role of ICT in collective management of public bads: The case of potato late blight in Ethiopia. World Development. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105366.

Dhillon, R.; Moncur, Q. Small-scale farming: a review of challenges and potential opportunities offered by technological advancements. Sustainability. 2023, 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115478.

Dolinska, A.; d’Aquino, P. Farmers as agents in innovation systems. Empowering farmers for innovation through communities of practice. Agricultural systems. 2016, 122-130. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2015.11.009.

Dutta, M.; Anand, K. Role of information communication technology in agriculture. International Journal of Novel Research and Development. 2023, 10, 863-870.

Henzel, J.; Hutchinson, B.S.; Thwaits, A. Using web services to promote library‐extension collaboration. Library hi tech. 2006, 1, 126-141. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/07378830610652158.

Ireri, D.M.; Awuor, M.; Ogalo, J.; Nzuki, D. Role of ICT in the dissemination and access of agricultural information by smallholder farmers in South Eastern Kenya. Acta Informatica Malaysia. 2021, 1, 31-41. http://doi.org/10.26480/aim.01.2021.31.41.

Kaniki, A. Community profiling and needs assessment. Knowledge, Information and Development: an African Perspective. Scottsville, South Africa: School of Human and Social Studies, University of Natal (Pietermaritzburg). 2001, 187-199.

King, M.; Kay, J. Radical uncertainty: Decision-making for an unknowable future, Hachette UK. 2020.

Kommey, R.; Fombad, M. Strategies for knowledge sharing among rice farmers: A Ghanaian perspective. Electronic Journal of Knowledge Management. 2023, 2, 114-129. http://dx.doi.org/10.34190/ejkm.21.2.2803.

Lwoga, E.T.; Ngulube, P.; Stilwell, C. Information needs and information seeking behaviour of small-scale farmers in Tanzania. Innovation: African Journas Online. 2010, 40, 82-103. https://doi.org/10.4314/innovation.v40i1.60088.

M’Sadeq, S.A.; Omer, F.A.; Abdullah, H.M.; Mohammed, N.I.; Mizzouri, N.S.; Russell, M.A.; Dickson, A.J.; Hirst, P.M. The reality of agricultural extension activities in the nineveh plain region post libaration (2017-2023). Mesopotamia Journal of Agriculture. 2023, 3, 22-36. http://dx.doi.org/10.33899/mja.2023.1.

Madan, S.; Maredia, K. Global Experiences in Agricultural Extension, Community Outreach & Advisory Services. In innovations in agricultural extension, Michigan State University Press, East Lansing, Michigan, USA. 2021, 1-16.

Mayfield-Smith, K. Social Media and Climate Communication. Communicating about Climate Science using Social Media: Exploring Discourse, Information Seeking And Climate Change Knowledge. MSc Thesis, University of Georgia, 2021.

Meitei, L.S.; Devi, T.P. Farmers information needs in rural Manipur: an assessment. Annals of Library and Information Studies. 56. 2009.

Momodu, M.O. Information needs and information seeking behaviour of rural dwellers in Nigeria: a case study of Ekpoma in Esan West local government area of Edo State, Nigeria.Library review. 2002, 8, 406-410. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/00242530210443145.

Naika, M.B.; Kudari, M.; Devi, M.S.; Sadhu, D.S.; Sunagar, S. Chapter 8 – Digital extension service: quick way to deliver agricultural information to the farmers. Food technology disruptions. 2021, 285-323. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-821470-1.00006-9.

Omulo, G.; Kumeh, E.M. Farmer-to-farmer digital network as a strategy to strengthen agricultural performance in Kenya: A research note on ‘Wefarm’platform. Technological Forecasting and Social Change. 2020, 120120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120120.

Ragasa, C. Effectiveness of the lead farmer approach in agricultural extension service provision: Nationally representative panel data analysis in Malawi. Land Use Policy. 2020, 104966. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104966.

Sennuga, S.O.; Oyewole, S.O.; Emeana, E. Farmers’ perceptions of agricultural extension agents’ performance in Sub-Saharan African communities. International Journal of Environmental and Agriculture Research. 2020, 1-12. http://dx.doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3866089.

Tiwari, S.P. Information and communication technology initiatives for knowledge sharing in agriculture.arXiv preprint arXiv:2202.08649. 2022. https://arxiv.org/abs/2202.08649.

Usman, Y.; Samaila, M.; Binyamin, A.; Abdullahi, S.; Mustafa, A.; Esther, S. A framework for Development of Agricultural Automated Information System. International Journal Of Science for Global Sustainability. 2021, 3, 6-6.

Academic Editor: Dr. Isabela Maria SIMION

Publisher Note: Regarding jurisdictional assertions in published maps and institutional affiliations ALSE maintain neutrality.

Abdullah Hojeen M., Dickson Amanda J., Hirst Peter M., M’Sadeq Shawkat A., Mizzouri Nashwan S., Mohammed Nabaz I., Omer Fathi A., Russell Mark A.