Alexandra Neamțu, Liviu Burtan, Dan Gheorghe Drugociu

ABSTRACT. Oesophageal foreign bodies are a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in small animals, especially in carnivores. Due to the possibility of complications such as perforation or tracheal compression, the patient may present an upper airway obstruction, which might become a medical emergency. Here, we describe a rare case of a large cervical foreign object in a cat and review the diagnostic and therapeutic approach of this condition. A 4-year-old female cat was referred to our clinic with signs of dyspnoea, dysphagia and regurgitation. The history and clinical exam suggested an oesophageal foreign body, subsequently radiographically confirmed. Because its shape and position did not allow endoscopic extraction, the foreign body was removed via ventral cervical oesophagostomy. Due to its location and large size, it was necessary to fragment the foreign body into two pieces for complete extraction without injuring the oesophageal walls. The patient had no postoperative complications and was discharged 7 days after surgery. In this condition, an early diagnosis, followed by an immediate surgical repair and a rigorous postoperative care, correlates with patient recovery and survival, being crucial in reducing the high morbidity and mortality rates that are usually associated.

Keywords: foreign body; oesophagus; cat; dyspnoea; dysphagia.

Cite

ALSE and ACS Style

Neamțu, A.; Burtan, L.; Drugociu, D.G. Cervical oesophagotomy in a cat for foreign body removal – case report. Journal of Applied Life Sciences and Environment 2021, 54(2), 123-131.

https://doi.org/10.46909/journalalse-2021-012

AMA Style

Neamțu A, Burtan L, Drugociu DG. Cervical oesophagotomy in a cat for foreign body removal – case report. Journal of Applied Life Sciences and Environment. 2021; 54(2): 123-131.

https://doi.org/10.46909/journalalse-2021-012

Chicago/Turabian Style

Neamțu, Alexandra, Liviu Burtan, and Dan Gheorghe Drugociu. 2021. “Cervical oesophagotomy in a cat for foreign body removal – case report” Journal of Applied Life Sciences and Environment 54, no. 2: 123-131.

https://doi.org/10.46909/journalalse-2021-012

View full article (HTML)

Cervical Oesophagotomy in a Cat for Foreign Body Removal – Case Report

Anastasia ȘTEFÎRȚĂ1,2, Ion BULHAC1, Lilia BRÎNZĂ1,3, Maria COCU1* and Vera ZUBAREVA1

Alexandra Neamțu1,*, Liviu Burtan1, Dan Gheorghe Drugociu1

1Iasi University of Life Sciences, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, 3 Mihail Sadoveanu Alley, 700490 Iasi, Romania

*E-mail: alexandra.neamtu21@gmail.com

Received: Mar. 30, 2021. Revised: May 28, 2021. Accepted: June 16, 2021. Published online: June 23, 2021

ABSTRACT. Oesophageal foreign bodies are a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in small animals, especially in carnivores. Due to the possibility of complications such as perforation or tracheal compression, the patient may present an upper airway obstruction, which might become a medical emergency. Here, we describe a rare case of a large cervical foreign object in a cat and review the diagnostic and therapeutic approach of this condition. A 4-year-old female cat was referred to our clinic with signs of dyspnoea, dysphagia and regurgitation. The history and clinical exam suggested an oesophageal foreign body, subsequently radiographically confirmed. Because its shape and position did not allow endoscopic extraction, the foreign body was removed via ventral cervical oesophagostomy. Due to its location and large size, it was necessary to fragment the foreign body into two pieces for complete extraction without injuring the oesophageal walls. The patient had no postoperative complications and was discharged 7 days after surgery. In this condition, an early diagnosis, followed by an immediate surgical repair and a rigorous postoperative care, correlates with patient recovery and survival, being crucial in reducing the high morbidity and mortality rates that are usually associated.

Keywords: foreign body; oesophagus; cat; dyspnoea; dysphagia.

INTRODUCTION

Oesophageal foreign bodies, cervical or intrathoracic, represent a frequent cause of dysphagia and regurgitation in small animals (Rousseau et al, 2007). This condition occurs more often in dogs than in cats due to the indiscriminate eating habits of dogs (Plunkett, 2013).

The most frequent oesophageal foreign bodies found in dogs and cats are bones, small toys, balls, needles, dental chews and fishhooks. If the foreign body remains stuck in the same position for several days, or puts excessive pressure on the walls, pressure necrosis and, subsequently, perforation may occur (Fossum, 2018). Food which cannot transcend through the obstruction will accumulate and may be regurgitated or cause oesophageal distention (Augusto et al., 2005).

The clinical signs associated vary depending on the site, as well as the degree and the duration of the obstruction (Hayes, 2009). Dysphagia and regurgitation are common, but occasionally, gagging, ptyalism, discomfort, respiratory distress and cyanosis may also be observed (Abd Elkader et al., 2020).

In comparison to other segments of the digestive tract, surgery of the oesophagus is associated with a higher percentage of postsurgical complications due to its structure, topography and function (Monnet, 2012). Complications appear frequently; in a study from 2016 (Sutton et al., 2016), they were present in 33.33% of cats and 54% of dogs with oesophageal surgery. Many of these complications, such as oesophageal perforation, esophagitis, wound dehiscence, leakage, stricture formation, aspiration pneumonia, infection, fistulas or abscess formation, can be overcome by appropriate treatment and a careful surgical technique (Griffon et al., 2016; Abd Elkader et al., 2020; Augusto et al., 2005).

Differential diagnoses for oesophageal foreign bodies are rabies, trigeminal neuropathy, periodontal disease, oropharyngeal or tracheal foreign body, oesophageal tumour, oesophageal stricture, diverticula or insect bites (Plunkett, 2013). Ingestion of furcula, an avian V-shaped bone, has been described as cause for pharyngeal and proximal oesophageal obstruction (Rendano, et al., 1988), but seldomly, the foreign body can migrate to the distal oesophagus, and its removal becomes a more difficult surgical procedure, as in this clinical case. This case report stands out because of the position, shape and large size of the avian bone in comparison with the size of the animal.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was conducted on a 4 year old female cat, mixed breed, 3.8 kg, with acute onset of lethargy, dysphagia, regurgitation, dyspnoea and open-mouth breathing. Respiratory and cardiac rate were increased. During medical consultation, the patient turned aggressive, and thus, a complete physical examination could not be performed. Based on history and clinical signs, the presence of a foreign body was suspected, and the patient was sent for a radiological examination. Since the clinical findings of this condition can also be observed in other diseases, the confession of the owner seeing or suspecting the patient ingesting the foreign object aids in making a presumptive diagnosis.

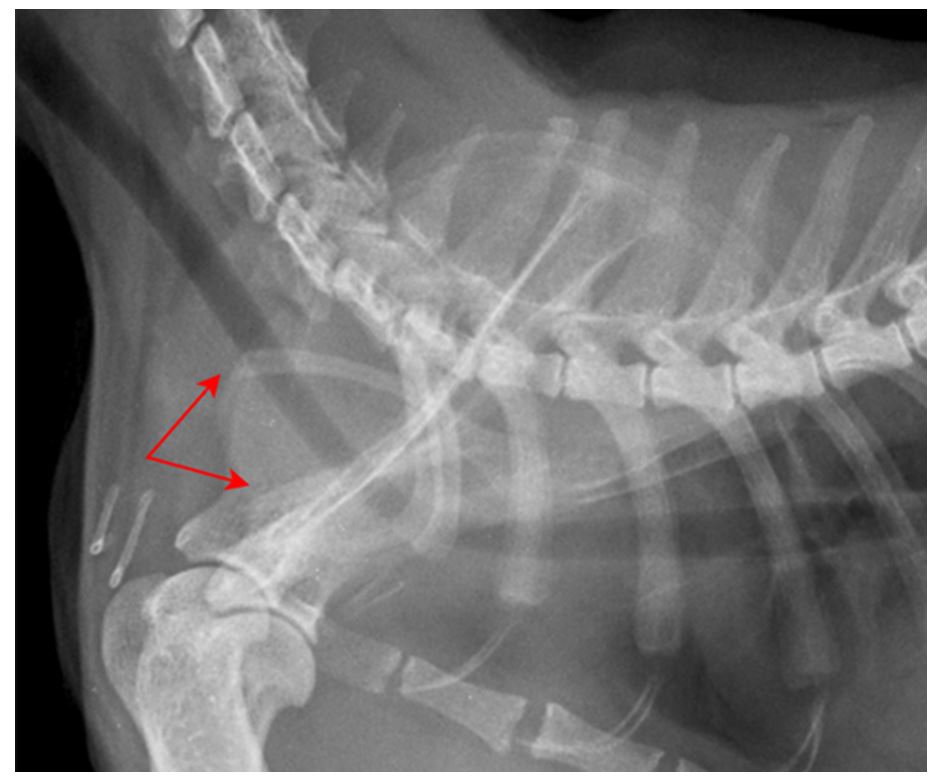

Radiographic imaging was performed, and a radiopaque foreign body was identified in the terminal region of the cervical oesophagus (Fig. 1). Considering its shape, an avian clavicula was suspected. Due to the shape, size, position, lodgement site and the high risk of perforation, the foreign object could not be retrieved manually using a pean artery forceps or through endoscopy; thus, oesophagostomy was the therapy of choice.

Figure 1 – Lateral radiographic view of the cat. Red arrows indicate the V-shape of the foreign body

Blood samples were taken, and the biochemical and haematological results were unremarkable.

After initial fluid resuscitation, anaesthesia was induced allowing palpation, and a firm mass in the cervical oesophagus was detected.

The anaesthesia protocol consisted of premedication with methadone 0.3 mg/kg intravenously and induction with propofol 6 mg/kg intravenously. The cat was intubated, and anaesthesia was maintained with isoflurane (2.5%).

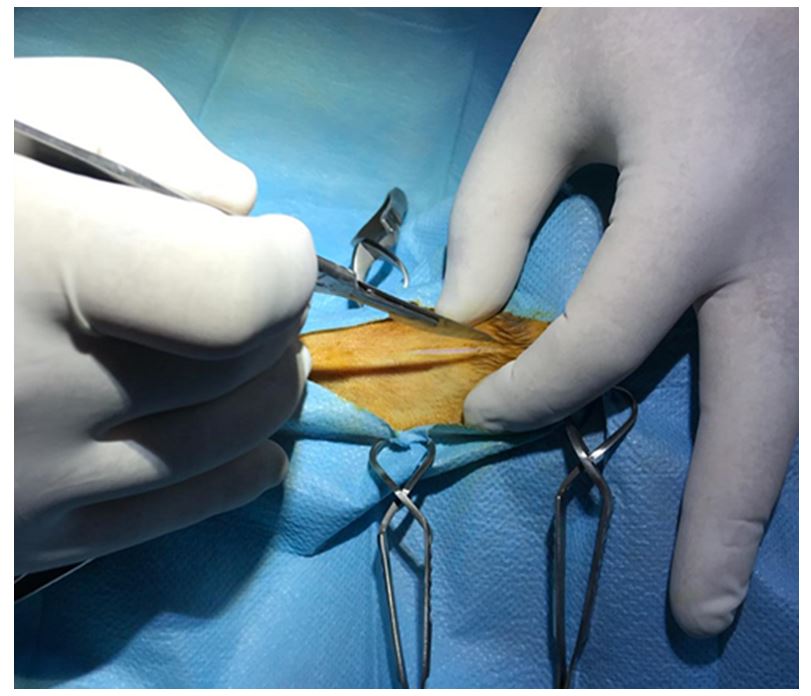

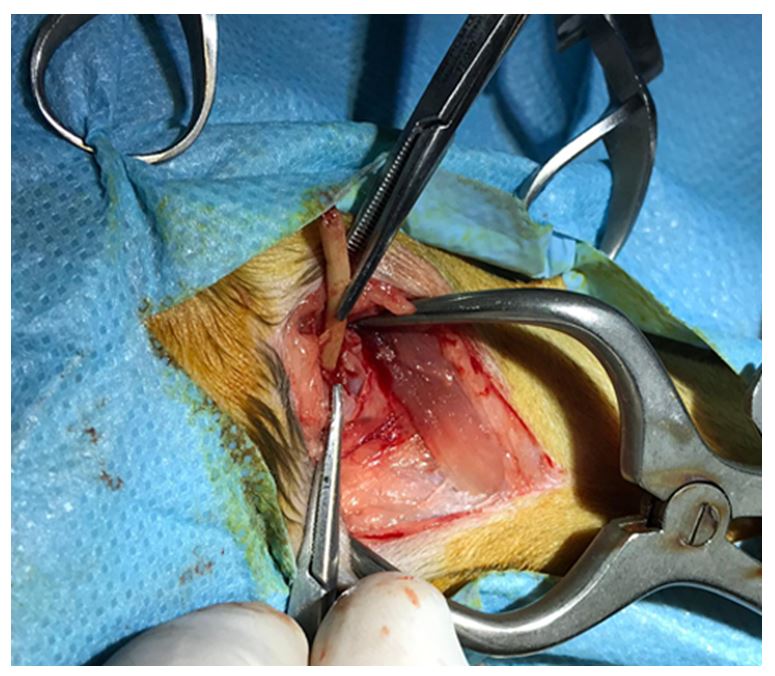

The cat was placed in dorsal recumbency, and the surgical field was prepared aseptically (Fig. 2).

The oesophagus was approached by a ventral midline incision of the skin (Fig. 3), separating the paired sternohyoid muscles and retracting the trachea to the right. Care had to be taken to avoid damaging the carotid artery, the jugular vein and the vagosympathetic trunk.

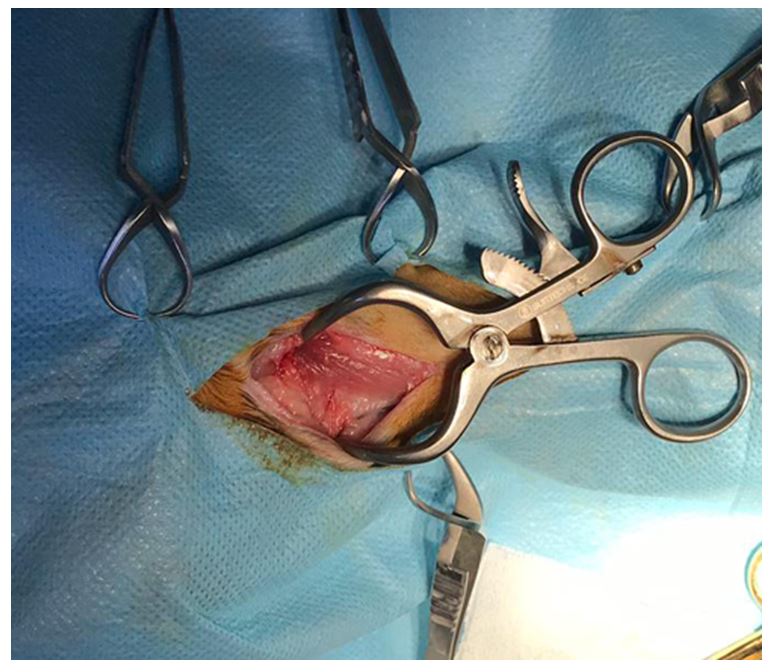

The oesophagus was identified (Fig. 4), and a first longitudinal section was made. However, to remove the avian bone, it was needed to be extended.

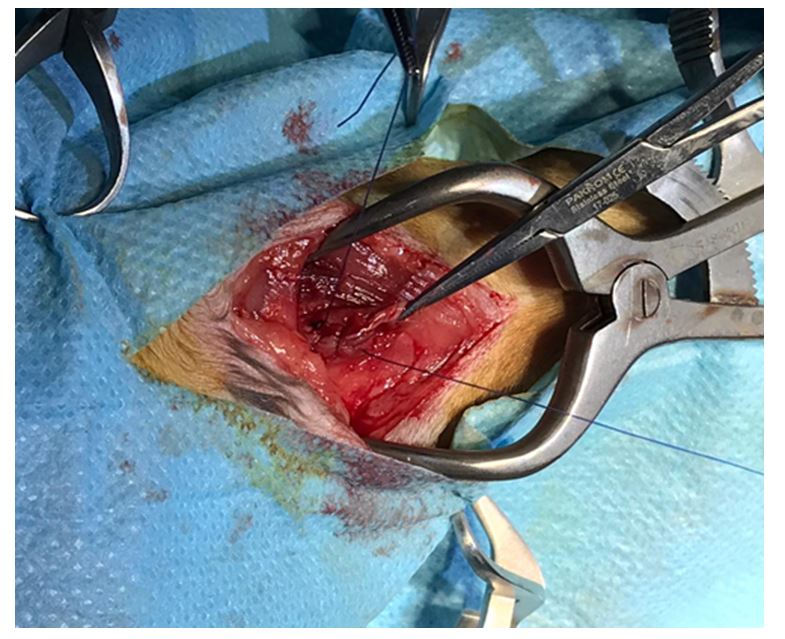

Considering its form and size, the bone could not be extracted until it was sectioned in two pieces. After cutting, gentle traction was used to extract the object from the lumen (Figs. 5 and 6).

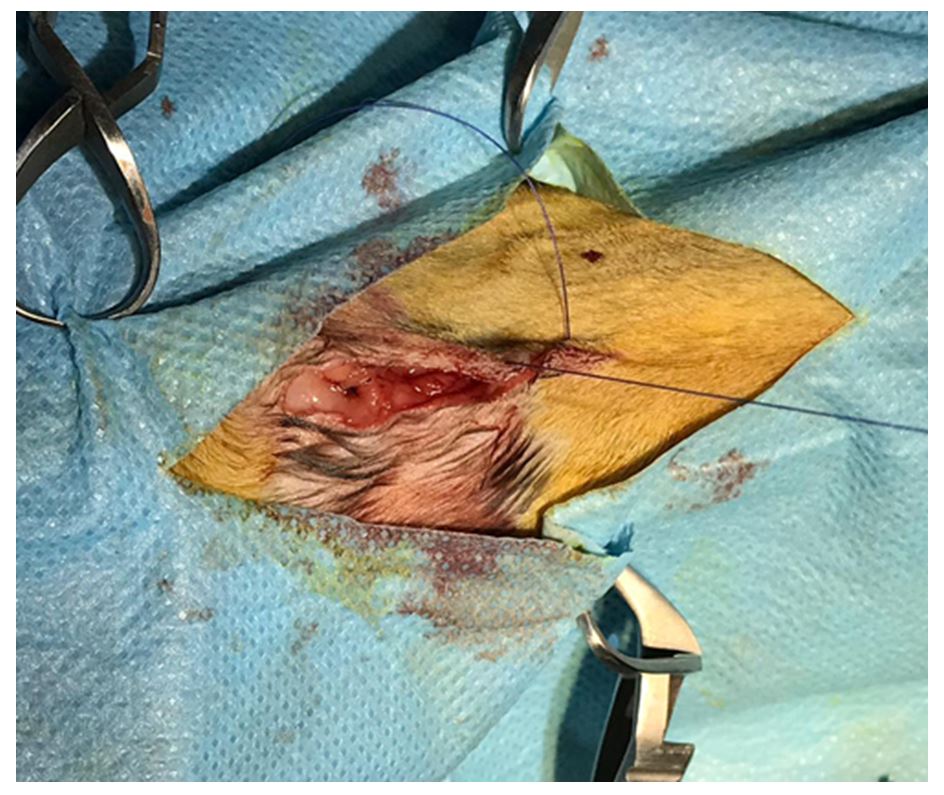

The following steps included inspecting the oesophageal lumen, evaluating mucosal integrity, wound cleaning and topical application of antiseptic ointment.

The oesophagus was sutured with Monocryl 3-0 in a two-layer pattern (Fig. 7): the first layer incorporated the mucosa and submucosa in a continuous suture, with the knots placed in the oesophageal lumen, and the second one was opposing the muscularis and adventitia with knots placed extraluminally. Subsequently, skin closure was performed (Fig. 8). Along with the bone, a clump of fur was also removed (Fig. 9).

Food and water were withheld in the first 3 days, with the patient receiving only intravenous fluid therapy with NaCl, glucose, Ringer and Duphalyte.

Figure 5 – Avian bone removal (first piece)

Oral food intake was resumed only after the fourth postoperative day, gradually, starting with water in small amounts, Viyo Recuperation Cat and blended wet food.

In addition to the postoperative diet, medical treatment involved antibiotic (amoxicillin and clavulanic acid 12.5 mg/kg) and antiinflammatory (meloxicam 0.2 mg/kg) therapy.

The owner was instructed about the postoperative care, and the cat was discharged after 1 week because she was in good condition and had no signs of leakage, infection or regurgitation after meals.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The diagnosis of oesophageal diseases is based on history clinical signs, imaging techniques (survey or contrast radiography) and/or endoscopy for direct visualisation (Fossum, 2018; Harari, 2004).

Foreign bodies, when located in the cervical oesophagus, may sometimes be identified by palpation. A definitive diagnosis, however, sometimes requires the combination of the techniques listed above. Even if the oesophagus is normally not radiographically visible in most cats and dogs, small amounts of swallowed air, different masses or various pathologies may be seen. Most oesophageal foreign bodies are radio-dense and visible on survey radiographs. Other radiographic findings commonly seen include pneumomediastinum or a soft tissue density surrounding the foreign body (the presence of mediastinitis and pleural effusion, usually suggesting oesophageal perforation) (Bojrab et al., 2014). If the signs indicate an oesophageal condition, and this cannot be confirmed by survey radiographs, contrast fluoroscopic or barium examination of the oesophagus may be indicated. If by plain or contrast radiography, the presence of a tumoral mass, foreign body, oesophageal obstruction or inflammation is suspected, an esophagoscopy may be performed to make a definitive diagnosis (Fossum et al., 2018)

In oesophageal disorders, some patients may present with respiratory signs without any history of regurgitation. Coughing, pulmonary crackles and fever may be seen, suggesting aspiration pneumonia (Fossum et al., 2018). The therapeutic plan has to be selected considering the foreign body site and nature and taking into account the complications involved. Surgical removal has been advocated in many studies as an important treatment method, especially when the foreign body is located far from the pharyngeal area and cannot be removed via forceps or has a shape that does not allow endoscopic removal. In a previous study, Abd Elkader (Table 1) stated that 26.7% of cats require oesophagostomy, whereas in other studies, only 18% of the animals needed surgical intervention (Abd Elkader et al., 2020; Binvel et al., 2018). Regarding postoperative care, after surgical foreign body removal, the patient should be carefully observed for 2 to 3 days for signs of oesophageal leakage. Regurgitation or vomiting can lead to aspiration pneumonia, which can be fatal. Antibiotics are administered if esophagitis, pneumonia, mediastinitis or pleuritis are present (Johnston et al., 2017).

Table 1

Locations, findings and therapeutic plans for oesophageal foreign bodies in cats

|

Location |

Percentage |

Findings |

Therapeutic plan |

|

At oesophageal entrance, caudal to pharynx |

63.3% |

13 cats with sewing needle protruding from oral cavity. |

Retrieval of foreign body using artery forceps |

|

One cat with needle protruding from epiglottis. |

|||

|

One cat with needle protruding from oesophageal wall. |

|||

|

Two cats with oesophageal abscess formation. |

|||

|

Two cats with bone foreign body. |

Retrieval of foreign body by esophagoscopy |

||

|

Mid-cervical region of oesophagus |

10% |

Bones were identified in all three cats. |

|

|

Terminal region of oesophagus at thoracic inlet |

26.7% |

Six cats with needle without complications. |

Retrieval of foreign body by cervical surgical intervention |

|

Two cats with needle perforation at the level of the 6th to 7th cervical vertebrae. |

Source: Abd Elkader et al. (2020)

According to Fossum (2018), treatment for oesophagitis, aspiration pneumonia and nutritional debilitation should be initiated before surgery. For oesophagitis, antacids, for example H2-blocking agents (e.g., famotidine 2 mg/kg PO or IV q12 hrs) or proton-pump inhibitors (e.g., omeprazol – 1 mg/kg PO q 24 hrs) with or without gastric prokinetics (metoclopramide 0.2 – 0.4 mg/kg PO, SC, or IV q 8 hrs) are administered, and water and food are withheld for 24 – 48 hrs to reduce oesophageal irritation. Intravenous fluids should be continued until oral intake resumes (Fossum et al., 2018). Most studies have shown that animals with oesophageal foreign bodies, regardless of their position, have some degree of oesophagitis; therefore, medical treatment for at least 7 days after surgery is imperative (Spielman et al., 1992; Sutton et al., 2016). Corticosteroid therapy (prednisone, 1.1 mg/kg PO q 24 hrs) may reduce the risk of stenosis, usually a complication of severe esophagitis. Oesophageal stricture is usually indicated by dysphagia and regurgitation, which appear 3 to 6 weeks after surgery, clinical signs that must be monitored postoperatively (Fossum et al., 2018). In some cases, if oral intake is not possible within 48 to 72 hrs after surgery, feeding should be performed through a gastrotomy tube. This type of feeding tube is selected because the oesophagus must be bypassed after oesophageal surgery, when the presence of a feeding tube could interfere with healing (Johnston et al., 2017).

The indications, contraindications, advantages and disadvantages of the feeding tubes are presented in Table 2. The patient from this case report was aggressive, and thus, placing and feeding, through a feeding tube, was decided to be taken into consideration only if needed. The feeding tube has to be used to maintain homeostasis because many cats develop lipidosis during periods of anorexia. Although histologic evidence of this disease developed within two weeks in an experimental model, clinical experience indicates that the syndrome can develop much more rapidly, such as 2 to 7 days. Physical examination commonly reveals jaundice, dehydration and hepatomegaly (Armstrong et al., 2009).

Table 2

Nutritional management of the surgical patient; different feeding tubes

|

Feeding tubes |

Indications |

Contraindications |

Major advantages |

Major disadvantages |

|

Naso-oesophageal tube |

– animals that are too debilitated to undergo anaesthesia for placement of other types of feeding tubes or that may need only short-term nutritional support (less than 1 week). |

– animals with an abnormal gag reflex, oesophageal dysfunction, coma or other conditions that increase the risk for aspiration – animals with persistent vomiting |

-ease of placement, tube care and feeding -acceptance by patients -patient’s ability to drink and eat around the tube -possibility of removal at any time after placement |

– small size of the tube – must use liquid enteral solution -vomiting may displace the tube – premature removal by the patient |

|

Pharyngostomy tube |

-anorexic patients or patients that are unable to ingest food orally (mandibular or maxillary fracture, cleft palate) |

– patients with oesophageal disorders (oesophageal stricture, removal of an oesophageal foreign body) |

– tube diameter, larger than the naso-oesophageal tube and accommodates a wider variety of diets |

– due to placement difficulties, they have been largely replaced by oesophagostomy tubes -anaesthesia needed |

|

Oesophagostomy tube |

– anorexic patients with disorders of the oral cavity or pharynx, with a functional gastrointestinal tract distal to the oesophagus. |

– patients with primary or secondary oesophageal dysfunction (oesophageal stricture/post-oesophageal surgery/removal of an oesophageal foreign body/oesophagitis or mega-oesophagus) |

-ease of placement -acceptance by patients -placement of large-bore tubes that allow blended diets -ease of tube care and feeding -patient’s ability to eat and drink around the tube |

– need for general anaesthetic for tube placement |

|

Gastrostomy tube

-blind percutaneous gastrostomy

-percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG)

-surgical placement |

-indicated in patients with a functional stomach and gastrointestinal tract that are anorexic, are at risk for PCM or are undergoing operations of the oesophagus, pharynx, larynx or oral cavity |

-patients with primary gastric disease (e.g., gastritis, gastric ulceration, gastric neoplasia) |

-ease of placement -patient tolerance -availability of large-bore feeding tubes – oral feeding can begin or continue while the gastrostomy tube is in place |

-need for specialised equipment and general anaesthesia -invasion of the peritoneal cavity and inability to remove the tube for at least 7 to 14 days (to allow adhesion formation) |

Source: Fossum et al. (2018); Johnston et al. (2017); Harari et al. (2004)

CONCLUSIONS

Esophagotomy, although it is a more invasive procedure, was the only therapy option for this patient considering the bone characteristics, which would have affected the oesophagus wall integrity if traction had been attempted using another procedure. Early examination, diagnosis and immediate surgical intervention improve the outcome of oesophageal foreign body condition and play a fundamental role in decreasing the complication occurrence. The patient from this case recovered uneventfully.

REFERENCES

Abd Elkader, N.A., Emam, I.A., Farghali, H.A. & Salem, N.Y. (2020). Oesophageal foreign bodies in cats: Clinical and anatomic findings. PLOS ONE, 15(6): e0233983, DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0233983

Armstrong, P.J. & Blanchard, G. (2009). Hepatic lipidosis in cats. Vet. Clin. North Am.: Small Anim., 39(3): 599-616, DOI: 10.1016/j.cvsm.2009.03. 003

Augusto, M., Kraijer, M. & Pratschke, K.M. (2005). Chronic oesophageal foreign body in a cat. J. Feline Med. Surg., 7(4): 237-240, DOI: 10.1016/ j.jfms.2004.12.006

Binvel, M., Poujol, L., Peyron, C., Dunie-Merigot, A. & Bernardin, F. (2017). Endoscopic and surgical removal of oesophageal and gastric fishhook foreign bodies in 33 animals. J. Small Anim. Pract., 59(1): 45-49, DOI: 10.1111/jsap.12794

Bojrab, M.J., Waldron, D.R. & Toombs, J.P. (2014). Current techniques in small animal surgery, 5th Ed., DOI: 10.1201/b17702

Fossum, T.W. (2018). Small animal surgery, 5th Ed., E-Book, Elsevier Health Sciences, 424-441.

Griffon, D. & Hamaide, A. (Eds.) (2016). Complications in small animal surgery, 319-323, DOI: 10.1002/9781 119421344

Harari, J. (2004). Small animal surgery secrets. Elsevier Health Sciences, 37-40, 141-146.

Hayes, G. (2009). Gastrointestinal foreign bodies in dogs and cats: a retrospective study of 208 cases. J. Small Anim. Pract., 50(11): 576-583, DOI: 10.1111/j.1748-5827.2009. 0078 3.x

Johnston, S.A. & Tobias, K.M. (2017). Veterinarys: Small animal expert consult, E-Book: 2-Volume Set., Elsevier Health Sciences, 1901-1913, 1690-1694.

Liptak, J.M., Monnet, E. & Campbell, V.L. (2014). Surgery of the thoracic wall: Small animal soft tissue surgery, 707-719, DOI: 10.1002/97811189975 05.ch72

Plunkett, S.J. (2013). Emergency procedures for the small animal veterinarian. Elsevier Health Sciences, 243-247.

Rendano, V.T., Zimmer, J.F., Wallach, M.S., Jacobson, R. & Pudalov, I. (1988). Inpaction of the pharynx, larynx, and esophagus by avian bones in the dog and cat. Veterinary Radiology, 29(5): 213-216, DOI: 10.1111/j.1740-8261.1988.tb01502.x

Rousseau, A., Prittie, J., Broussard, J.D., Fox, P.R. & Hoskinson, J. (2007). Incidence and characterization of esophagitis following esophageal foreign body removal in dogs: 60 cases (1999 2003). J. Vet. Emerg. Crit. Care, 17(2): 159-163, DOI: 10.1111/j.1476-4431.2007.00227.x

Spielman, B.L., Shaker, E.H. & Garvey, M.S. (1992). Esophageal foreign body in dogs: a retrospective study of 23 cases. J. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc., 28: 570e574.

Sutton, J.S., Culp, W.T.N., Scotti, K., Seibert, R.L., Lux, C.N., Singh, A., Kass, P.H. (2016). Perioperative morbidity and outcome of esophageal surgery in dogs and cats: 72 cases (1993-2013). J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc., 249(7): 787-793, DOI: 10.2460/javma.249.7.787