Jesse Zvikonyaukwa, Kudakwashe Musengi, Clarice P. Mudzengi, Andrew Tapiwa Kugedera

ABSTRACT. Wildlife has the potential to support people’s livelihoods and economic development in many African countries. The objective of the review was to evaluate the potential contribution of wildlife to people’s livelihoods and economic development in Africa. Several databases were searched to identify articles that have explored the contributions of wildlife to people’s livelihoods and economic development. The results indicate that wildlife contributes both consumptive and non-consumptive resources towards people’s livelihoods, with bush meat being the greatest consumptive contribution and employment the greatest non-consumptive contribution. Revenue collected from tourists, trophy hunting, and game viewing have been used for infrastructure and rural development. However, wildlife has declined in many African countries due to land redistribution, drought, habitat fragmentation, human population growth, and illegal hunting. Setting up law enforcement agents and creating community-based wildlife management could restore the benefits of wildlife.

Keywords: bush meat; edible fruits; game viewing; trophy hunting; wildlife resources.

Cite

ALSE and ACS Style

Zvikonyaukwa, J.; Musengi, K.; Mudzengi, C.P. The contributions of wildlife to people’s livelihoods and economic development in sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Applied Life Sciences and Environment 2023, 56 (4), 489-506.

https://doi.org/10.46909/alse-564112

AMA Style

Zvikonyaukwa J, Musengi K, Mudzengi CP. The contributions of wildlife to people’s livelihoods and economic development in sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Applied Life Sciences and Environment. 2023; 56 (4), 489-506.

https://doi.org/10.46909/alse-564112

Chicago/Turabian Style

Zvikonyaukwa, Jesse, Kudakwashe Musengi, and Clarice P. Mudzengi. 2023. “The contributions of wildlife to people’s livelihoods and economic development in sub-Saharan Africa” Journal of Applied Life Sciences and Environment 56, no. 4: 489-506.

https://doi.org/10.46909/alse-564112

View full article (HTML)

The Contributions of Wildlife to People’s Livelihoods and Economic Development in Sub-Saharan Africa

Jesse ZVIKONYAUKWA1*, Kudakwashe MUSENGI1,2, Clarice P. MUDZENGI1 and Andrew Tapiwa KUGEDERA1,3

1Department of Livestock, Wildlife and Fisheries, Great Zimbabwe University, Masvingo, Zimbabwe; email: cpmudzengi@gzu.ac.zw

2South African Environmental Observation Network: Arid Lands Node; email: kmusengi@gzu.ac.zw

3Agricultural Management, Zimbabwe Open University, 699 Nemamwa, Harare, Zimbabwe; email: kugederaandrew48@gmail.com

*Correspondence: jssbush@gmail.com

Received: Aug. 23, 2023. Revised: Nov. 20, 2023. Accepted: Nov. 23, 2023. Published online: Dec. 20, 2023

ABSTRACT. Wildlife has the potential to support people’s livelihoods and economic development in many African countries. The objective of the review was to evaluate the potential contribution of wildlife to people’s livelihoods and economic development in Africa. Several databases were searched to identify articles that have explored the contributions of wildlife to people’s livelihoods and economic development. The results indicate that wildlife contributes both consumptive and non-consumptive resources towards people’s livelihoods, with bush meat being the greatest consumptive contribution and employment the greatest non-consumptive contribution. Revenue collected from tourists, trophy hunting, and game viewing have been used for infrastructure and rural development. However, wildlife has declined in many African countries due to land redistribution, drought, habitat fragmentation, human population growth, and illegal hunting. Setting up law enforcement agents and creating community-based wildlife management could restore the benefits of wildlife.

Keywords: bush meat; edible fruits; game viewing; trophy hunting; wildlife resources.

INTRODUCTION

Wildlife resources are among one of the major sources of people’s livelihoods as well as economic and rural development in many African countries, including Zimbabwe, South Africa, Tanzania, and Kenya (Harilal et al., 2018; Mhuriro-Mashapa et al., 2018; Okello, 2015). Wildlife has been regarded as a readily available source for rural communities and to improve the economy of many countries – for example, Kenya, Zimbabwe, Botswana, South Africa, Namibia, and Uganda (Barnett, 2000; Barnett and Robinson, 2000; Wunder et al., 2014). In sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries, wildlife helps reduce rural poverty and provides daily products for food (Duguma et al., 2018; Mashapa et al., 2019; Mashapa et al., 2014). Trading of these resources has improved rural development and the standard of living of several rural populations (Chamber 2012; Barker et al., 2018; Mashapa et al., 2019). Communities adjacent to protected areas where wildlife resources are mainly found have benefited greatly over the past decades. Increasing rural population and economic degradation in SSA has driven rural communities to utilise and trade in wildlife resources as means of improving their livelihoods and standard of living (Tchakatumba et al., 2019). Population increases in rural communities have reduced land for agriculture, increased poverty, and caused food insecurity (Agrawal et al., 2014). However, the utilisation of wildlife resources by rural communities must be done in a sustainable way to conserve them for future use. This need for conservation creates a lot of challenges in the management of wildlife biodiversity throughout Africa, including Zimbabwe, South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, Botswana, Tunisia, and the Ivory Coast (Gandiwa et al., 2013; Golden et al., 2011; Martin and Shackleton, 2022; Shackleton, 2005). There are challenges when bush meat is not harvested from wild animals in a proper way, such as random killing without proper selection. Bush meat contributes to people’s livelihoods, reduces food insecurity, and acts as poverty alleviation strategy (Anadu et al., 1988; Antesy, 1991; Martin, 1983; Shackleton, 2005). Bush meat is a vital source of protein and its trade in rural communities generates income for rural populations (Caspery, 1999). An increased demand for bush meat and other wildlife resources has attracted the attention of many researchers in wildlife management to evaluate the contribution of wildlife resources on people’s livelihoods and economic development (Zvikonyaukwa et al., 2022). The literature includes ample information from rural community members about the benefits of wildlife resources. Therefore, there is need to evaluate and assess the contribution of wildlife resources utilised in rural communities. This review aimed to determine the contribution of wildlife resources on people’s livelihoods and rural and economic development. The hypothesis is that utilisation of wildlife resources significantly increases people’s livelihoods and rural and economic development in Africa.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A comprehensive search of Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Scopus was done from 10 May to 30 June 2022 to identify peer-reviewed papers published from 1980 to 2021 on the contributions of wildlife to people’s livelihoods and economic development in Africa. This search included peer-reviewed journals, edited books, academic theses, and reports from organisations. All papers covering research outside Africa was excluded. The keywords used for the search were “wildlife contribution”; “wildlife AND human livelihoods”; “wildlife contribution AND livelihoods OR economic development”; “wildlife AND economic development”; “wildlife and livelihood contribution”; “wildlife AND Africa”. The search yielded a total of 420 articles, of which 205 were removed because they were duplicates, did not focus on Africa, they were review articles, or they did not indicate a specific country.

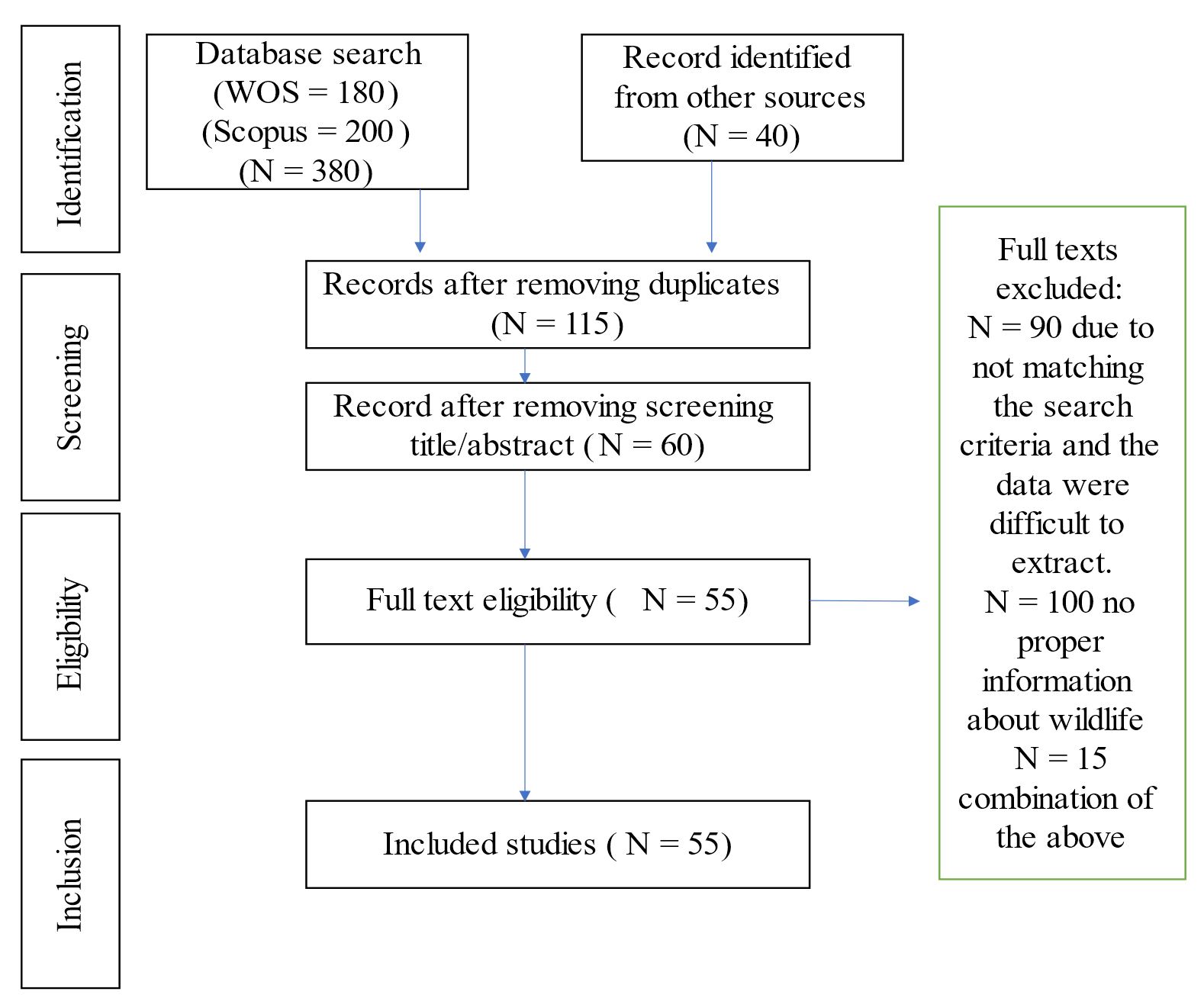

The remaining 115 articles were evaluated for their eligibility; 60 papers were removed because they did not cover the contribution of wildlife resources to people’s livelihoods and economic development. Hence, 55 articles were included in this review (Figure 1).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Contributions of wildlife to people’s livelihoods and economic development

Wildlife has been reported to contribute to people’s livelihoods through many dimensions that may have the capacity to reduce poverty and to improve economic development, human health, and nutrition. Besides, wildlife can provide tourism, trophy hunting, and boat cruising, among other activities (Zingi et al., 2022). Wildlife also generates income for many people across Africa and creates employment opportunities for both educated and non-educated people. In addition, wildlife resources provide ecotourism, which may increase benefits to both local communities and the country at large (Harilal and Tichaawa, 2020). Furthermore, proceeds from selling wildlife resources contribute towards infrastructure development in many areas where wildlife resources are found (Gandiwa et al., 2013; Martins and Shackleton, 2022). Moreover, these proceeds can be channelled back to the responsible authorities to improve management of wildlife resources to ensure the continuity of benefits. The contributions can be categorised into the following key areas: food, income generation, trade and revenue generation, tourism and employment and ecotourism.

Food

Rural communities living adjacent to wildlife areas mainly depend on their resources for food (Harison, 2015). Wildlife provides a good source of cost-efficient food for many rural communities. In Zimbabwe, communities adjacent to Mushandike Game Park and other wildlife protected areas harvest bush meat, vegetables, honey, fruits, and fish, which serve as food (Matseketsa et al., 2018). People obtain bush meat from wild animals, and this is an important source of protein (Golden et al., 2011). In Zimbabwe, people can harvest an average of 10–20 kilograms of fish per days at the Kariba, Kyle, and Tugwi-Mukosi Dams (Matseketsa et al., 2018; Zvikonyaukwa et al., 2022). This provides a good source of protein for several families as they buy fish on a regular basis. According to Golden et al. (2011), hunters in the Congo Basin kill approximately three animals per hunter on the day of hunting. In addition, bush meat can be sold to generate income. Consumption of bush meat reduces risks like kwashiorkor in children less than 5 years of age, improves protein content and boosts the human immune system.

Figure 1 – Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) flow chart with details on the, identification, screening and selection of articles considered in this review.

In the Congo Basin, from 2009 to June 2011 5–6 million tonnes of bush meat were harvested and contributed to approximately 80% of proteins and fats (Golden et al., 2011). This was also observed in Madagascar (Table 1), where consumption of bush meat reduces the chances of developing anaemia. Families that do not consume bush meat or meat have a 29% chance of being anaemic (Golden et al., 2011). Furthermore, bush meat and fish are among the most valuable resources extracted from wildlife by most leaving near rivers, forests, and game parks (Golden et al., 2011). Similarly, rural people in the Congo Basin consume 0.3 kilograms of bush meat on a daily basis as their major protein source rather than meat from domesticated animals (Golden et al., 2011). However, bush meat harvesting may contribute to reduce wildlife resources if it is not done in a sustainable way.

Wild food such as fruits and vegetables contribute to food availability in rural communities in several direct ways (Rasmussen et al., 2017). People living near wildlife habitats such as forests, rivers, game parks, and national parks have access to a wide range of resources such as fish, wild fruits, snails, honey, and resins (Rasmussen et al., 2016, 2017). In 2014 and 2015, people harvested an average of 5 kilograms of wild fruits, 20 litres of honey, and 5 kilograms of fish per week (Golden et al., 2011). Shackleton et al. (2002) reported that 91% of the population living near forests in South Africa extracts wild herbs and wild fruits as part of their livelihoods. Wildlife contributes nutrient sources such as zinc, iron, proteins, and vitamins C and E (FAO, 2014; Powell et al., 2013a, b; Rasmussen et al., 2017). Moreover, people collect edible fruits from trees such as Sclerocarya birrea, Tamarindus indica, Ziziphus mauritiana, and Invirgina gabonensis; these fruits can be used to extract juices and to make fruit cakes and butter (Chidumayo and Gumbo, 2010; Kupurai et al., 2021; Leakey, 2017). These fruit trees are underutilised and can contribute significantly towards people’s livelihoods (Kugedera, 2016; Maroyi, 2013). Most woody vegetation contributes towards livelihoods as people benefit in terms of fruits; medicine to cure several ailments; and a source of edible juice, edible worms, resins, tannins, and honey (Agrawal et al., 2014; Chidumayo and Gumbo, 2010; Kupurai et al., 2021; Mashapa et al., 2019; Rasmussen et al., 2017). People can sell these resources to generate income.

Income generation

Local people sell their traditional products such as dried indigenous vegetables, African chewing gum (Azanza gackeana), baobab (Adansonia digitata) and sorghum (Sorghum bicolor) juice to tourists to generate income. This income is used to meet household demands and to improve their food availability and other basic needs (Matseketsa et al., 2018).

This has also been reported in Namibia, where local people generate income by selling traditional products such as food and carvings to tourists (Ashley and Barnes, 1996). These actions improve food security and people’s livelihoods by improving food availability (Golden et al., 2011; Harilal et al., 2018).

Table 1

Contribution of wildlife towards food resources

|

Wildlife resource |

Country |

Reference |

|

Bush meat |

Congo Basin, Madagascar, Zimbabwe, Tanzania, Kenya, Zambia, Namibia, and Botswana |

Golden et al. (2011); Kupurai et al. (2021); Mhuriro-Mashapa et al. (2018); Matseketsa et al. (2018); (Rasmussen et al. (2016); Tchakatumba et al. (2019) |

|

Fish |

Zimbabwe and the Congo Basin |

Golden et al., (2011) |

|

Edible fruits |

Zimbabwe, Kenya, Botswana, Namibia, and Mozambique |

Chidumayo and Gumbo (2010); Kupurai et al. (2021); Martins and Shackleton (2022); Mashapa et al. (2014, 2019) |

|

Honey and medicines |

Namibia, the Congo Basin, Madagascar, and Zimbabwe |

Golden et al. (2011); Mashapa et al. (2014, 2019); Mhuriro-Mashapa et al. (2017) |

|

Juice and alcoholic beverages |

Zimbabwe, Zambia, South Africa, Kenya, Namibia, and Angola |

Chidumayo and Gumbo (2010); Golden et al. (2011); Kugedera (2016); Martins and Shackleton (2022); Shackleton et al. (2011) |

|

Edible worms |

Zimbabwe, Botswana, Zambia and South Africa |

Kupurai et al. (2021); Mutanga et al. (2015); Shackleton et al. (2011) |

|

Vegetables |

Zimbabwe, Uganda, Tanzania, South Africa, Namibia, and Ghana |

Chidumayo and Gumbo (2010); Kupurai et al. (2021); Manu and Kuuder (2017) |

The Musikavanhu people near Save Conservancy sell their products to tourists to generate income (Mashapa et al., 2018; Taylor, 2009). There are similar reports from Kenya, Uganda, Botswana, Senegal, and Rwanda: local communities benefit tremendously from selling their products to tourists (Golden et al., 2011; Harrison, 2015). Fishing is one of the major income-generating activities that benefits the livelihoods of many people living near dams and lakes in Zimbabwe, Kenya, Zambia, and Tanzania (Mashapa et al., 2019). In Zimbabwe, kapenta fishing in Kariba has improved the livelihoods of many people (Zvikonyaukwa et al., 2022).

Trade and revenue generation

Trade and use of wildlife resources such as non-timber forest products (NTFPs) have become pivotal for income generation in poor rural communities across the world (Kupurai et al., 2021; Martins and Shackleton, 2022; Shackleton and de Vos, 2022). Zingi et al. (2022) and Shackleton and de Vos (2022) indicate that about 5.6 billion people trade NTFPs globally, and 1.2 billion people depend highly on these products for income generation. The level of income generated from NTFPs varies from country to country and region to region (Martins and Shackleton, 2022), and income from these resources contributes to household incomes in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. The contribution of NTFPs to income generation is mainly influenced by household characteristics and access to markets (Zingi et al., 2022). Palm trading in Mozambique (Martins and Shackleton, 2022), marula juice trading in South Africa and Zimbabwe (Kugedera, 2016; Shackleton and Shackleton, 2005), and other wild edible fruits across Africa (Chidumayo and Gumbo, 2010) have contributed towards income generation for rural poor people in several regions across Africa, Asia, and Latin America.

Other activities have also generated income. For example, in Uganda, revenue from viewing gorillas increased from US$113 million to US$400 million during 2007 (FAO, 2010). This income boosted economic development in Uganda: the money was channelled to community projects like construction of clinics, schools, community centres, bridges, roads, maize mills, and water projects for local people to start irrigation (FAO, 2010). Utilisation of resources has also contributed to wildlife conservation and improved the livelihoods of many people in Uganda. There has been a similar situation in Zimbabwe: local communities have benefited from income generated from trading of wildlife resources by CAMPFIRE projects (Gandiwa et al., 2013). In South Africa and Namibia, utilisation of wildlife resources has generated substantial income, including trophy hunting (US$16,746,157), live game sales (US$757,816), wildlife viewing (US$14,308,426), and plant products (US$1,144,674). Most of the money generated was channelled to the development of rural areas with wildlife resources to improve the standards and to lure many tourists (Van-Schalkwyk et al., 2010). In Uganda, approximately US$4 billion generated from viewing the African elephant (Loxodonta africana) has been used to reduce poverty in rural communities (Okello, 2015).

Tourism and employment

Wildlife tourism can be categorised into consumptive and non-consumptive tourism. Non-consumptive tourism includes activities such as game viewing and boat cruising, which benefit people’s livelihoods directly and/or indirectly (Ashley and Barnes, 1996). An example of non-consumptive tourism is viewing animals under the guidance of local people, who are paid at the end of the day; they used this income to buy food and pay bills, among other things. Non-consumptive use of wildlife has created employment opportunities for local communities who act as guides because they know the behaviour of wildlife animals and their movement (Taylor, 2006; Figure 2). Consumptive benefits include hunting and fishing where local people pay a certain fee and are given permission to hunt and fish. Examples include Kariba, Lake Tanganyika, Tugwi-Mukosi, the Kyle Dam, and other national parks in South Africa (Golden et al., 2011). Fees paid by tourists can be used to improve rural development.

Trophy hunting is when tourists pay to hunt with the objective of selecting animals with desirable traits – such as large horns, bodies, and skulls – for their preferred use (Muposhi et al., 2016a). Tourists are accompanied by professional hunting guides who help them by providing information about animals and the area. If managed appropriately, trophy hunting contributes immensely to improve people’s livelihoods and the economy of many countries and rural development because the tourists pay huge sums of money in foreign currency (Damm, 2015; Jenks et al., 2002; Leader-Williams et al., 2005; Muposhi et al., 2016a,b; Nordbø et al., 2018). The benefits enjoyed through integrated conservation of wildlife are important as they help contribute to development projects such as construction of schools, clinics, and road networks, and serve to incentivise rural communities (Frost and Bond, 2008; Gandiwa, 2013; Gandiwa et al., 2013; Muposhi et al., 2016b). Trophy hunting has the capacity to improve wildlife conservation and protection by many African countries as this brings in a lot of money that can be used to develop rural areas (Muposhi et al., 2016b; Neleman and de Castro, 2016). Moreover, community-based wildlife management (CBWM) groups can be created to improve management of wildlife and thus people’s livelihoods. Trophy hunting in Zimbabwe offers incentives for the conservation of wildlife, the protection of habitats, and rural development through organisations such as CAMPFIRE (Gandiwa, 2013; Gandiwa et al., 2013; Muposhi et al., 2016b; Zisadza-Gandiwa et al., 2016). Trophy hunting in marginalised areas of Zimbabwe has been reported to contribute approximately 89.5% of total revenue generated, making it the most viable land-use activity (Lindsey et al., 2006; Muposhi et al., 2016b; Figure 3). This is important in areas such as Chiredzi, Malilangwe, Chizarira, Mana Pools National Park, and Matusadonha National Park (Zvikonyaukwa et al., 2022).

Although there have been several reports of a decline in wild animals in many African countries (Bouchè et al., 2011; Child, 2004; Craigie et al., 2010; Gandiwa, 2013; Gandiwa et al., 2013; Lindsey et al., 2006; Muboko et al., 2014, 2016; Muposhi et al., 2016b; Wolmer et al., 2004), trophy hunting in Zimbabwe has improved conservation of wild animals such as the African elephant (Zvikonyaukwa et al., 2022). The major cause of the population decline of these species is mainly drought, climate change, illegal hunting, bush meat trading, and overharvesting (Gandiwa et al., 2013; Muposhi et al., 2016b). Enforcement of laws that allow and regulate trophy hunting may have a positive effect on economic growth and rural development in African countries (Tchakatumba et al., 2019). Private areas such as Save Conservancy in Zimbabwe benefit a lot from trophy hunting through rates and other hidden revenues (Mashapa et al., 2019). These sites also create employment, help local communities, and improve people’s livelihoods via tax revenue and income from bush meat business centres established along the main roads in Zimbabwe (Zisadza-Gandiwa et al., 2016).

However, the land reform programme in Zimbabwe has caused habitat loss and land fragmentation, reducing the benefits from activities like trophy hunting (Wolmer et al., 2004). In addition, trophy hunting has faced the threat of being banned in Africa as a result of wildlife population declines due to poaching, overharvesting, illegal trading, and drought (Gandiwa, 2013; Muposhi et al., 2016b). For countries to continue to enjoy these benefits, there is need to come up with laws and to enforce them to regulate the management of wildlife resources in African countries.

Ecotourism and its contribution towards economic growth and rural development

Ecotourism has contributed significantly to improve people’s livelihoods and economic growth in Africa (Cahyadi and Newsome, 2021; Donohoe and Needham, 2006; Jaya et al., 2022; Mutiono, 2020; Sharpley, 2006; Zingi et al., 2022). Ecotourism plays a key role in providing revenue through trophy hunting, game viewing, and other activities (Harilal and Tichaawa, 2020). Furthermore, ecotourism is among the key drivers of sustainable community development in several countries across the globe (Nguyen et al., 2022; Nugroho et al., 2021), supporting rural communities and their livelihoods (Harilal et al., 2018; Pellis, 2019; Zingi et al., 2022). Ecotourism has the capacity to support growth and development of rural industries from which people can generate income and improve their livelihoods without depending much on the national budget (Jaya et al., 2022; Mondino and Beery, 2018). A good example is the Tsholotsho District in Zimbabwe, where ecotourism has been as major driver of economic growth and has transformed rural development programmes and benefitted local communities (Zingi et al., 2022). Moreover, local people have benefited through project development supported by non-governmental organisations, which have empowered local people (e.g., through construction of improved toilets to improve rural health).

In Indonesia, ecotourism has helped rural conflict resolution with the intervention of the local government via a rural district council, where people are trained in proper management and utilisation of resources (Jaya et al., 2022). Besides improving people’s livelihoods, ecotourism has helped to lure investments from other countries, which create employment opportunities and improve infrastructure (e.g., rehabilitation of roads, clinics, and schools; Campbell, 1999).

In the southeastern part of Zimbabwe, where Gonarezhou National Park is located, ecotourism has contributed to the development of rural growth points, including the construction of well-planned houses and a state-of-the-art training institution (Rupangwana Training Centre). This centre has attracted several organisations and companies to hold their training sessions and meetings, bringing in income to the department. In addition, ecotourism has facilitated easy networking between Zimbabwe and Mozambique due to tarred roads, which increase transport.

Local people are benefiting largely through selling their traditional products to people who converge at the training centre.

Infrastructure development

Wildlife has contributed significantly to economic development of many African countries, including Zimbabwe, Namibia, Kenya, Botswana and the Congo Basin (Mashapa et al., 2019; Powell et al., 2011). Most of the economic benefits are derived from harvesting wildlife resources, hunting, trading bush meat, and wildlife tourism (Van-Schalkwyk et al., 2010; Pellis, 2019). This has contributed to infrastructure development such as construction of the Mushandike College of Wildlife in Zimbabwe. Revenue from wildlife has been used to construct schools, clinics, roads and shopping centres and to renovate schools in Zimbabwe (Mashapa et al., 2019; Matseketsa et al., 2018). Revenue collected from wildlife boosts the economy in many countries and is used to develop local areas where wildlife is being managed.

Some examples are the development of Kariba Hotel, Victoria Falls International Airport and improved infrastructure in the Congo Basin, Namibia, Kenya, Botswana and Tanzania (Agrawal et al., 2014; Van-Schalkwyk et al., 2010). In Uganda, wildlife resources contribute to infrastructure development and revenue through tax collection (Table 2). This is also similar to Kariba, a town in Zimbabwe, which has benefited from wildlife tourism through infrastructure development (Zvikonyaukwa et al., 2022). In Kenya, most hotels are found in wildlife tourism centres (Mashapa et al., 2019; Zvikonyaukwa et al., 2022). Wildlife tourism has the potential to improve the national economy and to create employment for local communities.

Areas where wildlife resources are mainly found are located in rural areas, which are poorer than urban areas. This creates an opportunity for rural economic development through infrastructure development. In many countries, the rural areas that host wildlife resources have been developed to meet international standards for tourists (FAO, 2010). This has led to construction of clinics, hotels, good business centres, and well-tarred roads. For example, Binga in Zimbabwe is a remote area but has been well developed due to its wildlife (Table 2). Many organisations such as CAMPFIRE come in and develop the rural areas (Matseketsa et al., 2018; Tchakatumba et al., 2019). In Zimbabwe, CAMPFIRE has helped remote areas, such as Chipinge, Chiredzi, and Beitbridge, where clinics, schools, roads, and boreholes have been renovated, resurfaced, and drilled (Gandiwa et al., 2013; Mhuriro-Mashapa et al., 2018; Tchakatumba et al., 2019). Many new clinics and boreholes have also been established in the Lowveld of Zimbabwe near Gonarezhou National Park (Fakarayi et al., 2015; Machena et al., 2017; Mashapa et al., 2019; Reid, 2016; Tchakatumba et al., 2019). Local people are also employed in national parks, and this employment improves their standard of living and reduces poverty. There have been new developments in these areas, such as construction of state-of-the-art houses, and boreholes have been drilled to set up irrigation in their fields.

Other contributions of wildlife to local communities

Local people can benefit from programmes such as CAMPFIRE, which support community projects in many African countries where wildlife is managed. People have benefited from improved road network developments that link the villages and trade centres (FAO, 2011; Haule et al., 2002; Lindsey et al., 2011). Furthermore, local people have benefited from development projects in their villages and wild meat quotas set for their communities (Golden et al., 2011). Local people are employed in development projects such as road construction, business establishment, and construction of health care centres. These resources are left in the community to benefit the local people even if the wildlife population declines to a level that does not attract tourists (Mashapa et al., 2019). Activities such as game viewing and safari hunting may benefit local communities with revenues provided by tourists as tourist fees, employment, and a market of local products that seem to attract tourists (Lindsey et al., 2013; Mayaka et al., 2005; Mukanjari et al., 2013). In countries like Cameroon, local communities are only given a small share of revenues (e.g., 3% of revenue from safari hunting; Makaya et al., 2005). While this revenue does improve people’s livelihoods and is better than getting nothing, the local communities are not fully satisfied (Tchakatumba et al., 2019). If local communities are not given a sufficient share of the revenue, local people may begin to engage in poaching or support poaching as they will get cheap meat and get rid of problem animals that destroy their crops and cause loss of life. There is need for the government to support CBWM, in which communities’ control and manage the resources and thus conserve wildlife and receive a larger portion of the revenue (Mukanjari et al., 2013; Redpath et al., 2013). This may create a win-win situation where both government and local communities benefit from wildlife resources.

A way forward

Adoption of community-based ecotourism management can be a better option for organisations and companies involved in ecotourism activities (Clifton and Benson, 2006). This will allow local communities to take part in the management and utilisation of resources and to safeguard ecotourism (Rhama and Kusumasari, 2022).

Local authorities must also be included in the operation of ecotourism activities and draft rules and regulations that give preference to local communities regarding employment, revenue disbursement and infrastructure development (Kia, 2021).

Table 2

Contribution of wildlife to economic development in Africa

|

Economic development |

Countries |

Reference |

|

Schools |

Zimbabwe, Uganda, Namibia, Tanzania and Kenya |

Matseketsa et al. (2018); Muchapondwa et al. (2008); Okello (2015); Organisation for Economic Co-Development (2018); Tchakatumba et al. (2019); Van-Schalkwyk et al. (2010) |

|

Clinics and hospitals |

Zimbabwe, Kenya and Uganda |

Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (FAO, 2010); Mashapa et al. (2019); Okello (2015) |

|

Bridges and roads |

Zimbabwe, Uganda, Congo Basin and Madagascar |

Golden et al. (2011); Tchakatumba et al. (2019) |

|

Hotels |

Zimbabwe, Kenya and Uganda |

FAO (2010); Jesse et al. (2019); Okello (2015) |

|

Revenue |

Namibia, Uganda and Tanzania |

FAO (2010); Nelson (2004); Van-Schalkwyk et al. (2010); Nugroho et al. (2013). |

Traditional leaders, politicians, and other respected people in communities need to be included in the management or in boards that manage ecotourism activities. It is also important for researchers to evaluate bush meat as an essential part of the diet by determining the protein levels in different animals.

CONCLUSIONS

The paper has explored the contribution of wildlife to improve people’s livelihoods and economic development in rural communities, which usually have abundant wildlife resources. Wildlife directly and indirectly improves people’s livelihoods depending on the products extracted from it. Bush meat is the major contributor to improve people’s livelihoods in the Congo Basin, Madagascar, Namibia, Botswana, Tanzania, Uganda, and Zimbabwe, among other areas. Bush meat trading needs to be managed sustainably to prevent wildlife extinction. Many people are involved in hunting wildlife – fish, wild animals, and birds – to gather bush meat for human consumption as main source of protein and income generation (Golden et al., 2011). Apart from the consumptive benefits, there are non-consumptive benefits from game viewing, employment, and ecotourism, all of which create opportunities for local communities to sell their commodities to tourists to generate income. Apart from consumptive and non-consumptive benefits, wildlife has the capacity to improve the economic growth of many African countries through infrastructure development, including the construction of schools, clinics, roads, hotels, and tourism businesses. Apart from these benefits, in Zimbabwe, wildlife benefits have declined since 2000 due to the land redistribution programme that has facilitated habitat loss, land fragmentation, and poor management of wildlife resources. Moreover, wildlife has declined due to drought, climate change, illegal hunting, and illegal trade of wildlife products, which has led to trade bans. For countries to continue enjoy the contributions of wildlife, there is need to enforce laws that ensure conservation and protection of wildlife and its habitats.

Author Contributions: Conceptualisation, ZJ, MK and MCP; Methodology, ZJ and MCP; Writing-original draft preparation, ZJ; Writing-review and editing, ZJ, MK and MCP; Supervision, MCP. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest: Authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

Agrawal, A.; Wollenberg, E.; Persha, L. Governing agriculture-forest landscapes to achieve climate change mitigation. Global Environmental Change. 2014, 28, 270-280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.10.001.

Anadu, P.A.; Elamah, P.O.; Oates, J.F. The bushmeat trade in southwestern Nigeria: a case study. Human Ecology. 1988, 16, 199-208.

Antesy, E.O.A. Wildlife utilization in Liberia. Unpublished Report prepared for the World Fund for Nature (WWF), Gland, Switzerland, 1991.

Ashley, C.; Barnes, J. Wildlife use for economic gain the potential for wildlife to contribute to development in Namibia. DEA Research Discussion Paper 12, 1–23. Windhoek: Directorate of Environmental Affairs, 996.

Barnett, R. Food for thought: The utilization of wild meat in Eastern and Southern Africa. Traffic East/Southern Africa, Nairobi, Kenya, 2000.

Barnett, R.; Robinson, J.G. Hunting of wildlife in Tropical Forests. World Bank. Biodiversity Series-Impact Studies, Paper No. 76, 2000.

Bello, F.G.; Lovelock, B.; Carr, N. Constraints of community participation in protected area-based tourism planning: The case of Malawi. Journal of Ecotourism. 2017, 16, 131-151. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724049.2016.1251444.

Bouché, P.; Douglas-Hamilton, I.; Wittemyer, G.; et al. Will elephants soon disappear from West African Savannahs? PLoS ONE. 2011, 6, e20619.

Cahyadi, H.S.; Newsome, D. The post COVID-19 tourism dilemma for geoparks in Indonesia. International Journal of Geoheritage and Parks. 2021, 9, 199-211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgeop.2021.02.003.

Campbell, L.M. Ecotourism in rural developing communities. Annals of Tourism Research. 1999, 26, 534-553. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(99)00005-5

Caspery, H.U. When the monkey ‘goes butcher’: hunting, trading and consumption of bushmeat in the Tai National Park, Southwest Cote d’Ivoire. In M.A.F. Ros-Toten (ed.): Seminar Proceedings, Tropenbos Foundation, Wageningen, Netherlands, 1999.

Chidumayo, E.N.; Gumbo, D.J. The dry forests and Woodlands of Africa. Earth scan, USA, 2010.

Child, B. Building the CAMPFIRE paradigm: helping villagers protect African wildlife. PERC Rep. 22:2, 2004.

Clifton, J.; Benson, A. Planning for sustainable ecotourism: The case for research ecotourism in developing country destinations. Journal of Sustainable Tourism. 2006, 14, 238-254. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580608669057

Craigie, I.D.; Baillie, J.E.M.; Balmford, A.; et al. Large mammal population declines in Africa’s protected areas. Biological Conservation. 2010, 143, 2221-2228.

Dangi, T.B.; Gribb, W.J. Sustainable ecotourism management and visitor experiences: Managing conflicting perspectives in Rocky Mountain National Park, USA. Journal of Ecotourism. 2018, 17, 338-358. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724049.2018.1502250.

Damm, G.R. Branding hunting. African Indaba e-Newsletter. 2015, 13, 1-3.

Donohoe, H.M.; Needham, R.D. Ecotourism: The evolving contemporary definition. Journal of Ecotourism. 2006, 5, 192-210. https://doi.org/10.2167/joe152.0.

FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations). Economic and social significance of forests for Africa’s sustainable development. Nature & Faune. 2011, 25, 1-96.

FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations). African forestry and wildlife commission seventeenth session, African Forestry and wildlife week, Brazzaville, Republic of Congo: African Forests and wildlife: Response to the challenges of sustainable livelihood systems, 2010.

Frost, P.G.H.; Bond, I. The CAMPFIRE program in Zimbabwe: payments for wildlife Services. Ecology and Economy. 2008, 65, 776-787. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2007.09.018.

Gandiwa, E. Top-down and bottom-up control of large herbivore populations: a review of natural and human-induced influences. Tropical Conservation Science. 2013, 6, 493-505.

Gandiwa, E.; Ima, H.; Lokhorst, A.M.; Prins, H.H.T.; Leeuwis, C. CAMPFIRE and human-wildlife conflicts in communities adjacent to the northern Gonarezhou National Park, Zimbabwe. Ecology and Society. 2013, 18. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-05817-180407.

Golden, C.D.; Fernald, L.C.H.; Brashares, J.S.; Rasolofoniaina, B.J.R.; Kremen, C. Benefits of wildlife consumption to child nutrition in a biodiversity hotspot. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011, 108, 19653-19656. http://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1112586108

Harilal, V.; Tichaawa, T.M. Ecotourism and alternate livelihood strategies in Cameroon’s protected areas. EuroEconomica. 2018, 37.

Harilal, V.; Tichaawa, T.M. Community perception of the Economic Impacts of Ecotourism in Cameroon. African Journal of Hospitality. Tourism and Leisure. 2020, 9, 959-978. https://doi.org/10.46222/ajhtl.19770720-62.

Harilal, V.; Tichaawa, T.M.; Saarinen, J. Development without policy: Tourism planning and research needs in Cameroon, Central Africa. Tourism Planning and Development. 2018, 16, 696-705. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2018.1501732.

Harrison, E.P. Impacts of natural resource management programmes on rural livelihoods in Zimbabwe–the ongoing legacies of CAMPFIRE. In: PSA Conference, Arcata, CA, 2015. https://doi.org/10.14764/10.ASEAS-0027.

Haule, K.S.; Johnsen, F.H.; Maganga, S.L.S. Striving for sustainable wildlife management: the case of Kilombero Game controlled Area, Tanzania. Journal of Environmental Management. 2002, 66, 31-42. https://doi.org/10.1006/jema.2002.0572

Jaya, P.H.I.; Izudin, A.; Aditya, R. The role of ecotourism in developing local communities in Indonesia. Journal of Ecotourism. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1080/14724049.2022.2117368.

Jenks, J.A.; Smith, W.P.; DePerno, C.S. Maximum sustained yield harvest versus trophy management. Journal of Wildlife Management. 2002, 66, 528-535.

Kia, Z. Ecotourism in Indonesia: Local community involvement and the affecting factors. Journal of Governance and Public Policy. 2021, 8, 93-105. https://doi.org/10.18196/jgpp.v8i2.10789.

Mondino, E.; Beery, T. Ecotourism as a learning tool for sustainable development. The case of Monviso Transboundary Biosphere Reserve, Italy. Journal of Ecotourism. 2018, 18, 107-121. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724049.2018.1462371.

Kugedera, A.T. Cultivation practices and utilisation of Marula (Sclerocarya birrea (L) by the smallholder farmers of Vuravhi Communal Lands in Chivi, Zimbabwe. Msc Thesis, Department of Environmental Science, Bindura University of Science Education, 2016, 1-93. https://doi.org/10.31140/RG.2.2.20975.07844.

Kupurai, P.; Kugedera, A.T.; Sakadzo, N. Evaluating the potential contribution of Non Timber Forest Products (NTFPs) to smallholder farmers in semi-arid and arid regions: A case of Chivi, Zimbabwe. Research in Ecology. 2021, 3, 22-30.

Leader-Williams, N.; Milledge, S.; Adcock, K.; et al. Trophy hunting of black rhino Diceros bicornis: proposals to ensure its future sustainability. Journal of International Wildlife Law & Policy. 2005, 8, 1-11. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13880290590913705.

Leakey, R. Domestication potential of marula (Sclerocarya birrea subsp. caffra) in South Africa and Namibia: 3. Multiple traits selection. Agroforestry systems. 2005, 64, 51-59.

Lindsey, P.A.; Alexander, R.; Frank, L.G.; Mathieson, A.; Romañach, S.S. “Potential of trophy hunting to create incentives for wildlife conservation in Africa where alternative wildlife-based land uses may not be viable”. Animal Conservation. 2006, 9, 283-291.

Lindsey, P.A.; Romañach, S.S.; Tambling, C.J.; Chartier, K.; Groom, R. Ecological and financial impacts of illegal bushmeat trade in Zimbabwe. Oryx. 2011, 45, 96-111. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605310000153.

Lindsey, P.A.; Barnes, J.; Nyirenda, V.; Pumfrett, B.; Tambling, C.J.; et al. The Zambian wildlife ranching industry: scale, associated benefits and limitations affecting development. PLoS ONE. 2013, 8, e81761. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0081761.

Machena, C.; Mwakiwa, E.; Gandiwa, E. Review of the communal areas management programme for indigenous resources (CAMPFIRE) and community based natural resources management (CBNRM) models. Harare: Government of Zimbabwe and European Union, 2017.

Manu, I.; Kuuder, W.C.J. Community based ecotourism and livelihood enhancement in Sirigu, Ghan. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science. 2017, 2, 97-108.

Maroyi, A. Local knowledge and use of Marula (Sclerocarya birrea (A. Rich.) Hochst.) In South-central Zimbabwe. Indian Journal of Traditional Knowledge. 2013, 12, 398-403.

Martin, G.H.G. Bushmeat in Nigeria as a natural resource with environmental implications. Environmental conservation. 1983, 10, 125-134.

Martin, A.; Caro, T.; Borgerhoff-Mulder, M. Bushmeat consumption in western Tanzania: A comparative analysis from the same ecosystem. Tropical Conservation Science. 2012, 5, 352-364. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/194008291200500309.

Martins, A.R.O.; Shackleton, C.M. The contribution of wild palms to the livelihoods and diversification of rural households in southern Mozambique. Forest Policy and Economics. 2022, 142, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2022.102793.

Mashapa, C.; Gandiwa, E.; Muboko, N. Socio-economic and ecological outcomes of woodland management in Mutema-Musikavanhu communal areas in Save Valley, southeastern lowveld of Zimbabwe. Journal of Animal and Plant sciences. 2019, 29, 1075-1087

Mashapa, C.; Gandiwa, E.; Mhuriro-Mashapa, P.; Zisadza-Gandiwa, P. Increasing demand on natural forest products in urban and peri-urban areas of Mutare, eastern Zimbabwe: Implications for sustainable natural resources management. Nature & Faune. 2014, 28, 42-48.

Matseketsa, G.; Chibememe, G.; Muboko, N.; Gandiwa, E.; Takarinda, K. Towards an understanding of Conservation-Based Costs, benefits and Attitudes to local people living adjacent to Save Valley Consevancy, Zimbabwe. Scientifica. 2018, 6741439. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/6741439

Mayaka, E.B.; Hendricks, T.; Wesseler, J.; Prins, H. Improving the benefits of wildlife harvesting in Northern Cameroon: A co-management perspective. Ecological Economics. 2005, 54, 67-80.

Mhuriro-Mashapa, P.; Mwakiwa, E.; Mashapa, C. Determinants of communal farmers’willingness to pay for human-wildlife conflict management in the periphery of Save Valley Conservancy, south eastern Zimbabwe. The Journal of Animal and Plant Sciences. 2017, 27, 1678-1688.

Mhuriro-Mashapa, P.; Mwakiwa, E.; Mashapa, C. Socio-economic impact of human-wildlife conflicts on agriculture based livelihood in the periphery of Save Valley Conservancy, southern Zimbabwe. The Journal of Animal and Plant Sciences. 2018, 28, 903-914.

Muboko, N.; Muposhi, V.; Tarakini, T.; Gandiwa, E.; Vengesayi, S.; Makuwe, E. Cyanide poisoning and African elephant mortality in Hwange National Park, Zimbabwe: a preliminary assessment. Pachyderm. 2014, 55, 92-94.

Muboko, N.; Gandiwa, E.; Muposhi, V.; Tarakini, T. Illegal hunting and protected areas: tourist perceptions on wild animal poisoning in Hwange National Park, Zimbabwe. Tourism Management. 2016, 52, 170-172.

Mukanjari, S.; Bednar-Friedl, B.; Muchapondwa, E.; Zikali, P. Evaluating the prospects of benefits sharing schemes in protecting mountain gorillasin Central Africa. Natural Resource Modeling. 2013, 26, 455-479. https://doi.org/10.1111/nrm.12010.

Muposhi, V.K.; Gandiwa, E.; Makuza, S.M.; Bartels, P. Trophy hunting and perceived risk in closed ecosystems: flight behaviour of three gregarious African ungulates in a semi-arid tropical savanna. Austral Ecology. 2016a, 44, 809-818. https://doi.org/10.1111/aec.12367.

Muposhi, V.K.; Gandiwa, E.; Makuza, S.M.; Bartels, P. Trophy Hunting, Conservation, and Rural Development in Zimbabwe: Issues, Options, and Implications. International Journal of Biodiversity. 2016b. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/8763980.

Mutanga, C.N.; Muboko, N.; Gandiwa, E. Protected area staff and local community viewpoints: A qualitative assessment of conservation relationships in Zimbabwe. PLoS ONE. 2017, 12, e0177153. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0177153.

Mutiono, M. Developing of integrative ecotourism in Waifoi Village, Papua Barat, Indonesia. Jurnal Pemberdayaan Masyarakat: Media Pemikiran Dan Dakwah Pembangunan. 2020, 4, 345-366. https://doi.org/10.14421/jpm.2020.04-06

Neleman, S.; de Castro, F. Between nature and the city: Youth and ecotourism in an Amazonian ‘forest town’ on the Brazilian Atlantic Coast. Journal of Ecotourism. 2016, 15, 261-284. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724049.2016.1192181.

Nguyen, C.H.; Nguyen, A.T.; Truong, Q.H.; Dang, N.T.; Hens, L. Natural resource use conflicts and priorities in small islands of Vietnam. Environment, Development and Sustainability. 2022, 24, 1655-1680. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-021-01502-0.

Nordbø, I.; Turdumambetov, B.; Gulcan, B. Local opinions on trophy hunting in

Kyrgyzstan. Journal of Sustainable Tourism. 2018, 26, 68-84. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2017.1319843.

Nugroho, I.; Negara, P.D. The role of leadership and innovation in ecotourism services activity in Candirejo Village, Borobudur, Central Java, Indonesia. World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology. 2013, 7, 2073-2077. https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.1087283.

Nugroho, I.; Hanafie, R.; Negara, P.D.; Sudiyono, S.; Yuniar, H.R. Social capital and social capacity in rural ecotourism development. Indonesian Journal of Geography. 2021, 53, 153-164. https://doi.org/10.22146/IJG.55662

Okello, M.M. Economic Contribution, Challenges and Way Forward for Wildlife-Based Tourism Industry in Eastern African Countries. Journal of Tourism and Hospitality. 2015, 3.

Pellis, A. Reality effects of conflict avoidance in rewilding and ecotourism practices – The case of Western Iberia. Journal of Ecotourism. 2019, 18, 316-331. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724049.2019.1579824.

Powell, B.; Hall, J.; Johns, T. Forest cover, use and dietary intake in the East Usambara Mountains, Tanzania. International Forestry Review. 2011, 13, 305-317.

Powell, B.; Iockowitz, A.; Mcmullin, S.; Jamnadass, R.; Padoch, C.; Pinedo-Vasque, M.; Sunderland, T. The role of forests, trees and wild biodiversity for nutrition sensitive food systems and landscapes. In: Expert Background Paper for the International Conference on Nutrition (ICN 2). FAO, Rome, 2013a.

Powell, B.; Maundu, P.; Kuhnlein, H.V.; Johns, T. Wild Foods from Farm and Forest in the East Usambara Mountains, Tanzania. Ecology of Food and Nutrition. 2013b, 52, 451-478.

Putra, H.W.S.; Hakim, A.; Riniwati, H.; Leksono, A.S. Community participation in development of ecotourism in Taman Beach, Pacitan District. Journal of Indonesian Tourism and Development Studies. 2019, 7, 91-99. https://doi.org/10.21776/ub.jitode.2019.07.02.05.

Rasmussen, L.V.; Bierbaum, R.; Oldekop, J.A.; Agrawal, A. Bridging the practitioner-researcher divide: indicators to track environmental, economic and sociocultural sustainability of agricultural commodity production. Global Enviromental Change. 2017, 42, 33-46.

Rasmussen, L.V.; Mertz, O.; Christensen, A.E.; Danielsen, F.; Dawson, N.; Xaydongvanh, P. A combination of methods needed to assess the actual use of provisioning ecosystem services. Ecosystem Services. 2016, 17, 75-86. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2015.11.005.

Redpath, S.M.; Young, J.; Evely, A.; et al. Understanding and managing conservation conflicts. Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 2013, 28, 100-109.

Reid, H. Ecosystem-and community-based adaptation: learning from community-based natural resource management. Climate Development. 2016, 8, 4-9. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2015.1034233.

Rhama, B.; Kusumasari, B. Assessing resource-based theory in ecotourism management: The case of Sebangau National Park, Indonesia. International Social Science Journal. 2022, 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1111/issj.12345.

Shackleton, C.; Shackleton, S.E.; Buiten, E.; Bird, N. The importance of dry woodlands and forests in rural livelihoods and poverty alleviation in South Africa. Forest Policy Economy. 2007, 9, 558-577.

Sharpley, R. Ecotourism: A consumption perspective. Journal of Ecotourism. 2006, 5, 7-22. https://doi.org/10.1080/1472404060866844.

Taylor, R.D. Case study: CAMPFIRE (Communal areas management program for indigenous resources), Zimbabwe. Washington (DC): USAID. USAID-FRAME Paper, 2006.

Taylor, R.D. Community based natural resource management in Zimbabwe: the experience of CAMPFIRE. Biodiversity Conservation. 2009, 18, 2563-2583. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-009-9612-8.

Tchakatumba, P.K.; Gandiwa, E.; Mwakiwa, E.; Clegg, B.; Simukayi, N. Does the CAMPFIRE programme ensure economic benefits from wildlife to households in Zimbabwe? Ecosystems and People. 2019, 15. https://doi.org/10.1080/26395916.2019.1599070.

Van-Schalkwyk, D.L.; McMillin, K.W.; Witthuhn, R.C.; Hoffman, L.C. The contribution of wildlife to sustainable natural resources utilisation in Namibia: A review. Sustainability. 2010, 2, 3479-3499. https://doi.org/10.3390/su2113479.

Wolmer, W.; Chaumba, J.; Scoones, I. Wildlife management and land reform in southeastern Zimbabwe: a compatible pairing or a contradiction in terms? Geoforum. 2004, 35, 87-98.

Wunder, S.; Angelsen, A.; Belcher, B. Forests, livelihoods, and conservation: broadening the empirical base. World Dev. 2014a, 64, 1-11.

Wunder, S.; Börner, J.; Shively, G.; Wyman, M. Safety nets, gap filling and forests: a global-comparative perspective. World Dev. 2014b, 64, 29-42.

Zingi, G.K.; Mpofu, A.; Chitongo, L.; Museva, T.; Chivhenge, E.; Ndongwe, M.R. Ecotorism as a vehicle for local economic development: A case of Tsholotsho District Zimbabwe. Cogent Social Sciences. 2022, 8, 1-13: https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2022.2035047.

Zisadza-Gandiwa, P.; Gandiwa, E.; Muboko, N. Preliminary assessment of human–wildlife conflicts in Maramani Communal Area, Zimbabwe. African Journal of Ecology. 2016, 54, 500-503. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/aje.12282/epdf.

Zunza, E. Local Level Benefits of CBNRM: The Case of Mahenye Ward CAMPFIRE, Zimbabwe [MSc Dissertation]. Harare: Center for Applied Social Sciences (CASS): University of Zimbabwe, 2014.

Zvikonyaukwa, J.; Gwazani, R.; Kugedera, A.T. Contribution of wildlife tourism industry to livelihoods and economy. Amity Journal of Management Research. 2022, 5, 706-712.

Academic Editor: Prof. Dr. Daniel Simeanu

Publisher Note: Regarding jurisdictional assertions in published maps and institutional affiliations ALSE maintain neutrality.

Kugedera Andrew Tapiwa, Mudzengi Clarice P., Musengi Kudakwashe, Zvikonyaukwa Jesse